Key Takeaways:

(Inside Science) — Pluto is not a planet, according to the vast majority of astronomers. While it orbits the Sun and is mostly round, it does not orbit alone, instead traversing the solar system accompanied by several moons, including a companion almost half its size. This is the main reason for its demotion in 2006.

A few holdouts continue to debate this definition, but they may have a new epistemic challenge to contend with: What makes a star? When a distant object is too small and too faint to be a star, but also too big to be an exoplanet, and is not solitary, how can you be sure what it is?

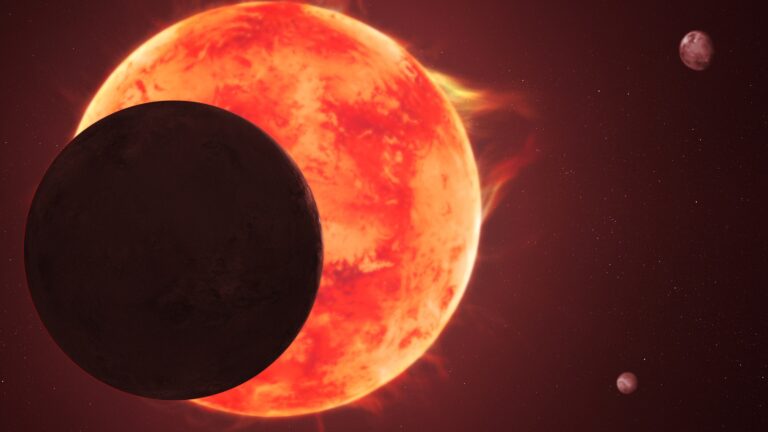

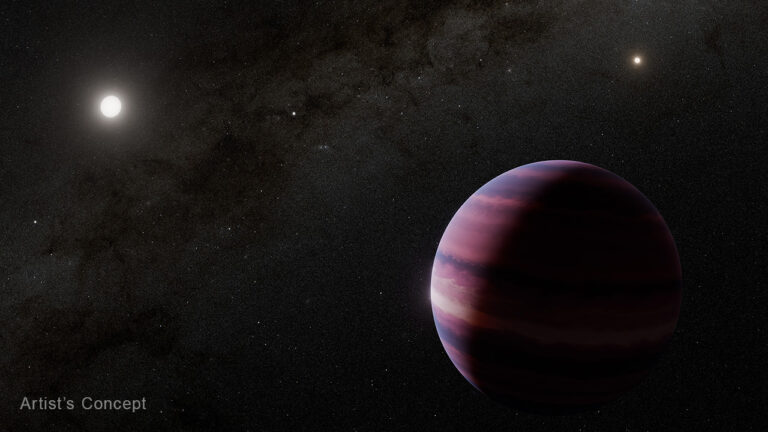

Astronomers recently found a most mystifying example of such in-between objects: a pair of planetlike orbs, some 450 light-years away, that aren’t bound to any host star and travel the void together. They are brown dwarfs, which are dim not-quite-stars that never grew large enough to fuse hydrogen. But they are tiny, even by brown dwarf standards, and they look more like planets than anything stellar, according to Clémence Fontanive of the University of Bern in Switzerland, the astronomer who discovered them. The larger brown dwarf of the pair sits along the boundary astronomers use to differentiate stars from planets, around 13 times the mass of Jupiter. The smaller one weighs in at only eight times the size of Jupiter.

“According to that definition, it should be a planet. But if you define that a planet should form around a star, then it’s not really a planet, either,” Fontanive said. She calls them “planetary mass brown dwarfs.”

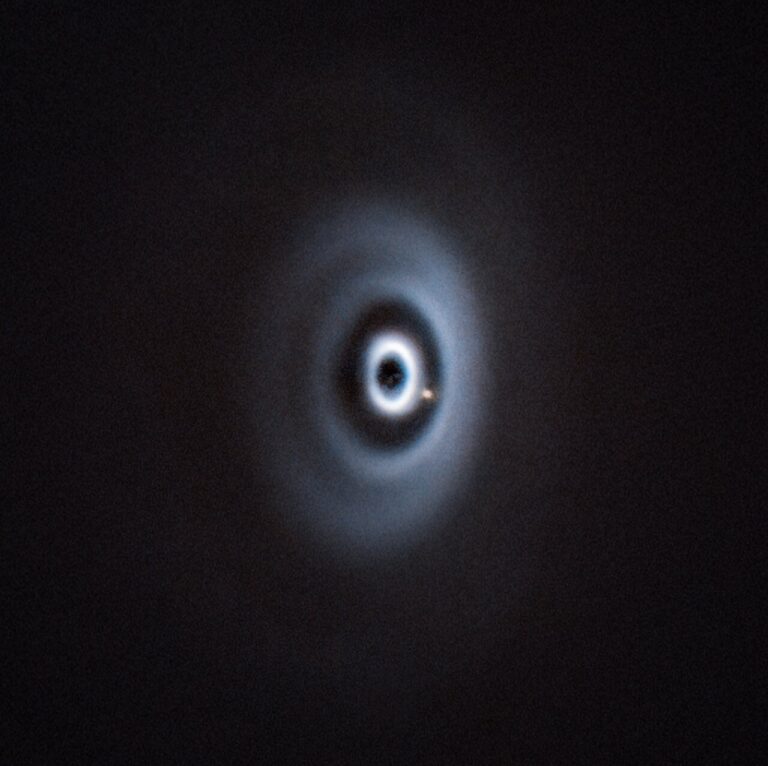

The objects are found in the constellation Ophiuchus, near the celestial equator. They are about fives times farther apart from each other than Pluto is on average from the Sun, which means they are just barely a pair. Fontanive confirmed their relationship by studying previous measurements of the system captured in a sky survey. They likely have the weakest gravitational connection of any binary discovered so far, she said.

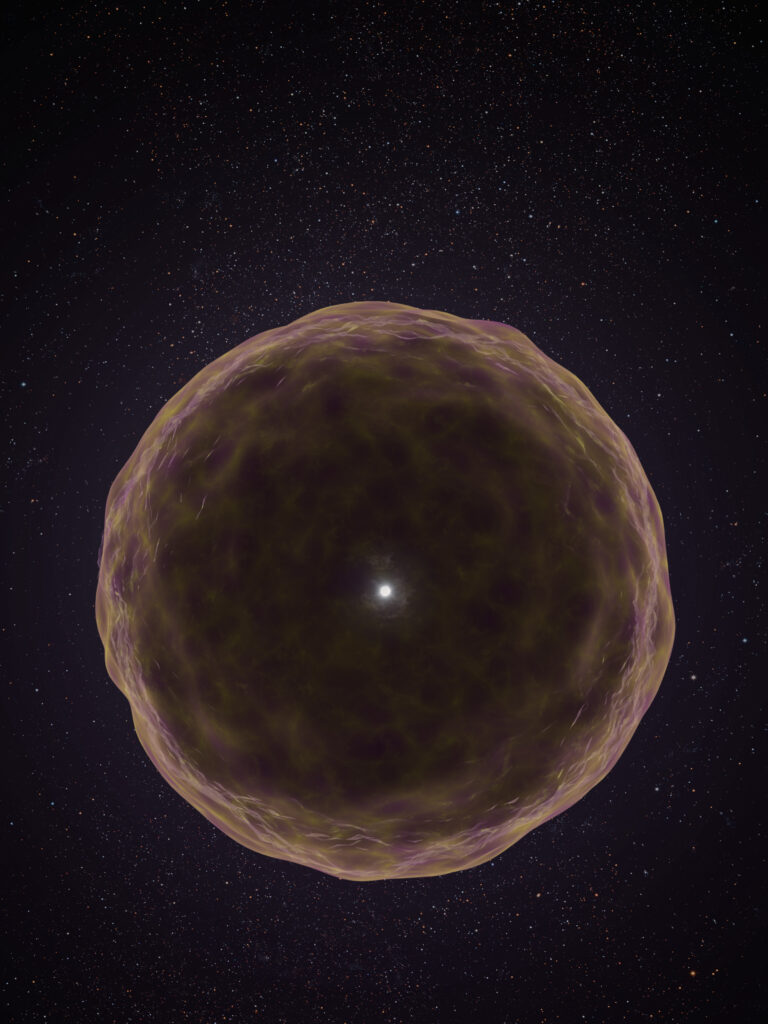

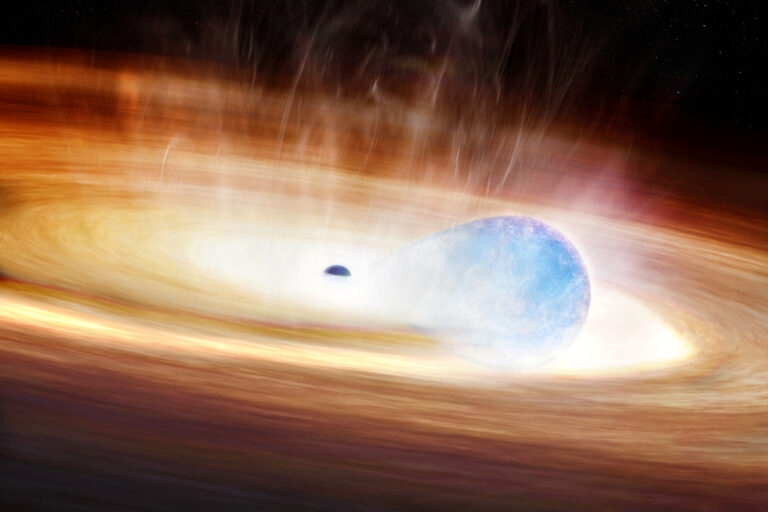

Stars usually ignite after they accumulate enough hydrogen gas to start fusing it into heavier elements. Planets usually form around these baby stars, in a swirling disk of dust and gas left over from the star’s birth.

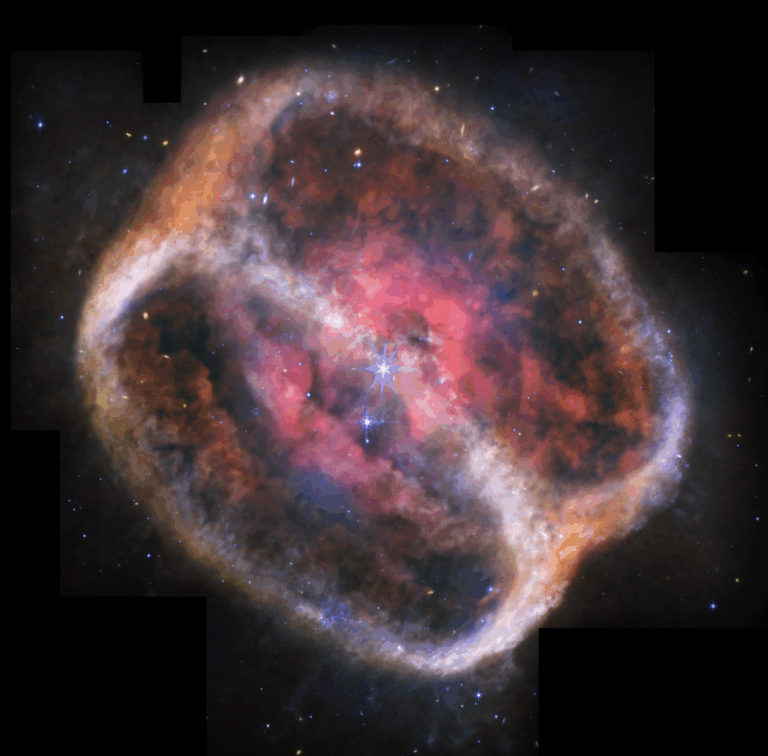

Brown dwarfs are somewhat in between both objects, but more like stars. They are larger and warmer than planets, and unlike gas giant planets, they can fuse deuterium, a form of hydrogen with one neutron, into helium. But brown dwarfs can’t create the main nuclear reactions that power stars like our Sun. They are destined to cool down and grow faint. Many are likely too chilly to sufficiently warm any planets that might orbit them. Astronomers have found about 2,000 brown dwarfs so far, in a wide range of sizes. But the new pair in Ophiuchus are so planetlike and so barely connected that they push the boundary of planet versus star.

“Because we have only found a handful of these very low-mass binaries, we don’t really know what the landscape looks like,” said Will Best, an astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin who studies brown dwarfs and was not involved in the new work. He said he would not consider them a star and a planet, or a planet and a moon, but a binary system.

The universe may hold many such things, but because brown dwarfs are brightest in their youth, they spend the rest of their lives cooling down and growing dimmer. “When they’re a billion years old, they will be basically invisible,” Best said.

Fontanive and her team can’t be sure exactly how old the newly discovered objects are, but she estimates about 3 million years old — barely an eyeblink in the typical life history of a star — because that’s roughly the age of other stars that formed in the same region of space. There’s a chance they could still be growing, which Fontanive wants to confirm with further observations of their light.

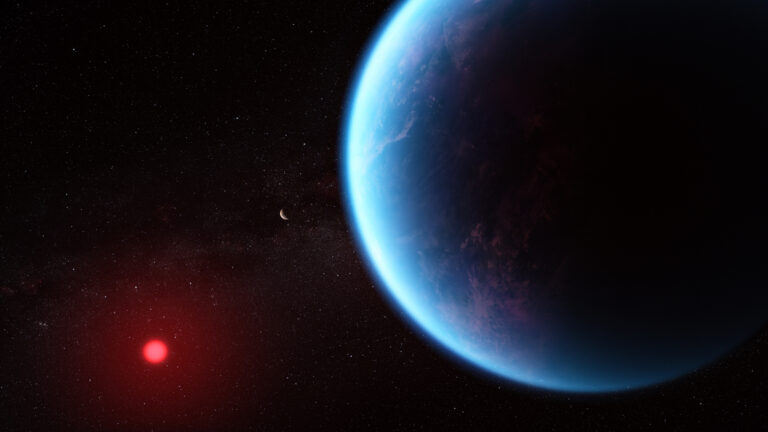

Fontanive went looking for low-mass brown dwarfs in part because she is interested in studying giant exoplanets. Most of those are extremely close to their stars, making them difficult to study. She found these worlds using the Hubble Space Telescope and confirmed that they are a binary system by combing through 14 years of data from an observatory called the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on Mauna Kea. A paper detailing the discovery has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The objects lend some weight to one of two theories, currently under vigorous debate, that explain how planets are made in the afterbirth of stars. Some astronomers argue that worlds coalesce in the turbulent gas flows surrounding infant stars. Others argue that they clump together through static and other forces, gradually accumulating more dust and larger rocks to grow into worlds. The presence of these odd starless orbs could indicate the first method happened here, Fontanive said. The system’s youth indicates that these objects formed very quickly and the accretion method would take too long. What’s more, the second method is more violent — think asteroid collisions and planetary bombardments –and would likely have broken the bond between the two worlds, she said.

“You need something strong enough to pull you away from the gravity of the main star, and if you have something strong enough to do this, it seems very unlikely that these binary objects would stay together,” she said. “Or it’s possible that they formed where we see them, the way that a star would form, and just never accreted enough mass or material to become hotter.”

Best said the discovery challenges astronomers’ concepts of both planets and stars.

“We have a sun and we have planets, and nothing in between, but the universe makes everything in between,” he said. “Maybe we should find some other way to define planets — by how they form, or whether they orbit a star. This paper is definitely stretching those questions.”