Key Takeaways:

- Andromeda is a large galaxy, much bigger than our Milky Way.

- Andromeda contains about a trillion stars.

- Andromeda is moving towards our Milky Way.

- In billions of years, Andromeda and the Milky Way will merge.

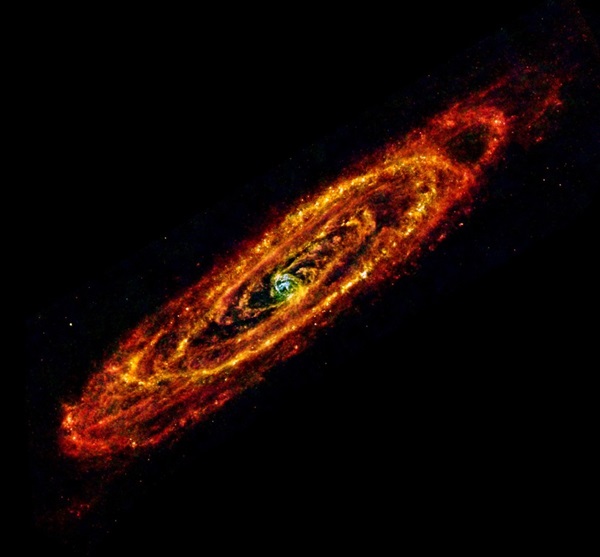

The Andromeda Galaxy, or M31, is the nearest large neighbor of our Milky Way, though it sits some 2.5 million light-years away. That makes it the most distant object regularly visible with the naked eye.

By some estimates, the Andromeda Galaxy contains roughly one trillion stars. And it stretches more than 200,000 light-years in diameter. That’s significantly bigger than the Milky Way, which more recent estimates suggest is 150,000 light-years across (though the exact boundary of where either of these galaxies “end” is a bit nebulous). Astronomers are still struggling to get an accurate count, but our galaxy also appears to have roughly a quarter to a half as many stars as Andromeda.

The Andromeda Galaxy’s discovery

Ancient skygazers have probably pondered the nature of this blurry spot for many thousands of years. However, the oldest known discovery of the Andromeda Galaxy dates to 964 A.D., when a Persian astronomer named Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi wrote a book about “Fixed Stars.” In it, he called out Andromeda, and also noted the position of the Large Magellanic Cloud, a much more petite satellite galaxy of our Milky Way. The Andromeda Galaxy was referred to as a “small cloud” in the heavens.

But it wasn’t until the 1800s that astronomers started realizing just how special Andromeda was. That’s because until roughly a century ago, scientists thought our Milky Way was the entire universe.

For some time, observers using their telescopes to hunt comets had been turning up “nebulae” — a term that described basically any fuzzy night-sky object that was not a comet. Ones with spiral shapes, like Andromeda, were called spiral nebulae. But in 1864, an English astronomer named Sir William Huggins used a prism to break apart and analyze the various colors of light from a variety of nebulae. When he did, Huggins noticed that the light spectra of M31 was very different from some of these other nebulae.

The great galaxy debate

In the decades ahead, other astronomers started noticing supernovae exploding in Andromeda, too. One astronomer in particular, Heber Curtis, used the known brightness of these explosions to calculate the distance to Andromeda. He estimated that this “spiral nebulae” was an unprecedented 500,000 light-years away, which would put it well outside the confines of our Milky Way.

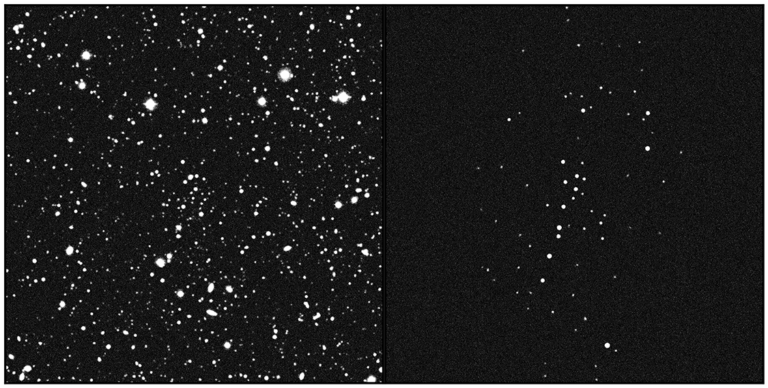

And a few years before, Vesto Slipher, an astronomer at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, had turned the 24-inch Clark Telescope on M31 and measured it moving toward us at an astonishing rate. Meanwhile, Slipher’s measurements of more than a dozen other spiral nebulae showed that all but three were moving away from Earth. His evidence supported the idea that Andromeda wasn’t within our Milky Way. It lived outside it. This served as the first strong evidence for an expanding universe.

These findings were presented as some of the opening salvos in the famous “Great Debate” between Curtis and Harlow Shapley (the latter an ambitious young scientist). Many researchers agreed with Shapley’s long-held view that the Milky Way was the entire universe. But the evidence seemed to suggest that Andromeda, as well as other mysterious spiral nebulae, were actually so-called “island universes.” The debate would take years to finally settle.

Milkomeda: the Milky Way and Andromeda collide

We now know the Andromeda Galaxy truly is an island universe distinct from our own. But it won’t always be that way.

As Slipher’s observations first showed, over the next five billion years or so, the Milky Way and Andromeda will draw uncomfortably close together. The pair will interact in glancing blows, ripping stars from one another into long, drawn out tails.

As seen from Earth, the Andromeda Galaxy will loom large in our night sky during these encounters. But as the two eventually tangle up entirely, they’ll merge into one enormous group of stars. But instead of a spiral galaxy, the final object will be an elliptical. Astronomers call this future galaxy Milkomeda, and these kinds of mergers happen all the time.

However, while a collision between two galaxies might seem like it could only end in destruction, galaxy mergers often lead to extreme bursts of star formation. This too will be visible from our solar system — although, humans probably won’t survive long enough to see it.

Nonetheless, the aftermath of the Milkomeda collision will leave our night sky awash with bright, new stars. So, instead of this galactic clash killing either of the galaxies, the mergers might even usher in new life.