Key Takeaways:

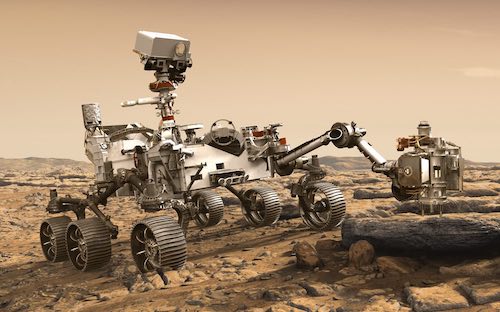

On 18 February, the Mars2020 mission will touch down in a small crater called Jezero near the Martian equator. The mission includes a rover called Perseverance that will explore the area, analyze rocks and gather samples to be returned to Earth by a later mission due to fly in 2026. The mission also includes a helicopter drone called Ingenuity that will scout ahead, looking for intriguing targets to study.

Jezero is interesting because it was once filled with liquid water and so should contain significant evidence of its effects. Even more tantalizing is the possibility that the crater once hosted life. Indeed, part of the Mars2020 mission is to search for signs of life and any biosignatures preserved in the rock.

Planetary geologists have long studied Jezero, marking it as a potential landing site for Mars missions. But the decision to send a rover there has made it the target of much more study.

In particular, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, currently orbiting the Red Planet, has sent back numerous visible and infrared images of the region that have allowed geologists to study remotely the types of rock Perseverance is likely to encounter.

Now Adrian Brown from NASA headquarters in Washington DC says this work has helped to create a remarkably detailed picture of the rocks that Perseverance will find and how they might have been altered by the action of water. Brown also discusses the idea that the rocks in Jezero crater are similar to Earth-bound outcrops in Warrawoona, Australia, which contain the oldest fossilized evidence of life on Earth.

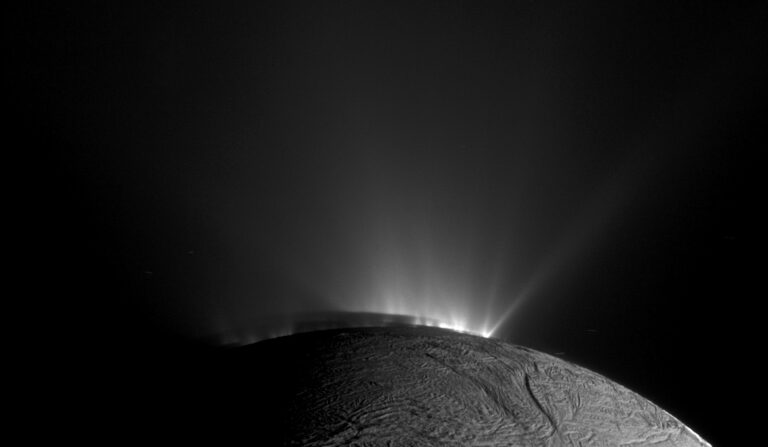

First some background. Mars was once very different from the dry arid planet we see today. Some 4 billion years ago, Mars’s many volcanoes, some of the biggest in the Solar System, began pumping huge volumes of gas and dust into the atmosphere.

This trapped energy from the Sun causing temperatures to rise and allowing liquid water to pool on the surface. The atmosphere might even have supported clouds and rainfall, creating conditions that were ripe for the emergence of life.

But about 3.7 billion years ago, the planet began to cool, along with its interior, shutting down the planet’s internal magnetic dynamo and destroying its magnetic field.

As the surface cooled, the liquid water froze at the poles or became permafrost. This created the conditions for massive flooding. Whenever an asteroid impact heated an area, the permafrost melted, sending torrents across the surface. Today, the planet is scarred by the huge channels carved by these floods.

Planetary geologists think Jezero crater filled with water at least twice but that the resulting lakes were long lived, lasting perhaps 10 million years and finally disappearing about 3.7 billion years ago. “This may be the final time water flowed on Mars,” says Brown, who presented this paper at the 23rd International Mars Society Convention in October.

The crater is about 50 kilometers in diameter and well-studied using the cameras aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The images at various frequencies of visible and infrared light reveal the composition of the rock and also its grain size, which reveals how it has weathered over time.

Brown says this shows the crater was originally formed in rock consisting of olivine, a mineral containing iron, magnesium and silicates, as well as well carbonates. Brown says an important discovery is a rocky outcrop beyond the waterline that reveals the unaltered rock as it originally formed. This will become an essential reference for the mission, against which altered rocks can be compared.

Water works

Within the crater, clay has formed in various areas, which geologists believe can only happen in the presence of water, which will have carried the necessary minerals from surrounding areas. This is likely to have formed in layers, which may be visible near the shoreline.

The most intriguing line of investigation is Brown’s comparison between the rocks in Jezero crater and those at Warrawoona in Australia. Back in 1983, paleobiologists discovered evidence of fossilized cells in these rocks, which formed some 3.5 billion years ago. They represent the oldest geological evidence of life on Earth.

That immediately raises the tantalizing possibility that similar evidence might be present in Jezero crater. If so, an important question is whether Perseverance will be able to gather this evidence and analyze it in the necessary detail.

That’s a big ask, even for a mission designed to look for signs of life. “The limitations in spaceflight-ready instrumentation and the remote location of the scientific team limit the extent of scientific analyses that can be done by rover missions to Mars,” Brown points out.

But even if not, Perseverance will gather samples that will later be returned to Earth by a sample return mission. The advantage of such an approach is that the rocks can be studied in more detail by a wider variety of instruments. “Inspired by the Apollo samples, which still continue propel new lunar science discoveries, we anticipate that the analyses of the samples returned by MSR will rely on future instrumentation that may not even exist today,” says Brown.

Brown says NASA and the European Space Agency have agreed to work on the sample return mission together. “The nominal launch date is planned for 2026, with a nominal return of samples by 2031,” he says. So for a definitive answer to any questions about signs of life on Mars, we will probably have to wait until then.

Ref: Mars2020 and Mars Sample Return arxiv.org/abs/2012.08946