Key Takeaways:

- A significant challenge for a manned Mars mission is the provision of medical treatment, as transporting sufficient pharmaceuticals is impractical due to cost, weight limitations, and the lengthy transit time to Mars.

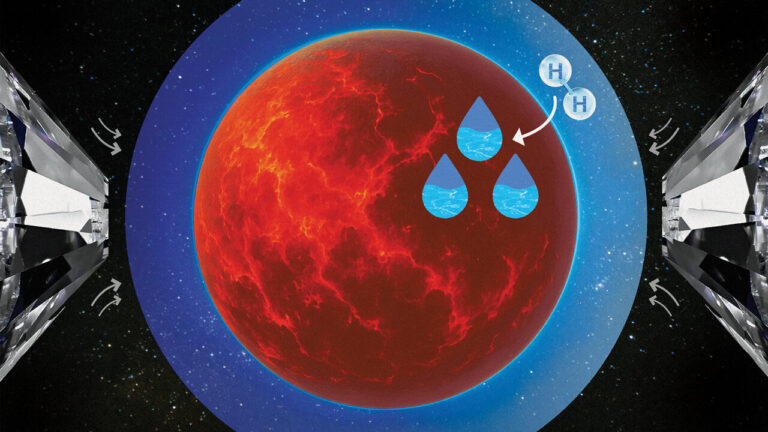

- NASA's CUBES project aims to address this by developing synthetic biology techniques to produce pharmaceuticals on Mars using genetically modified plants (e.g., lettuce, spinach) and microbes (e.g., spirulina).

- These methods involve introducing genes into plants to produce therapeutic proteins, utilizing techniques like agrobacterium transformation and gene guns, with a focus on creating stable, predictable drug production across plant generations.

- While the primary application is for Mars missions, this research also has potential terrestrial applications, particularly in addressing future challenges related to climate change, resource scarcity, and global population growth.

Science fiction writers have been dreaming of a crewed mission to Mars for over a century. But it wasn’t until Wernher von Braun published the English translation of his book, The Mars Project, in 1953 that the idea was plucked out of the realm of fiction and into reality.

The Mars Project makes an impressive case for the technical feasibility of getting to Mars, outlining with extraordinary specificity how 10 space vehicles, each manned with 70 people and using conventional propellant, could achieve a round-trip voyage to the Red Planet.

Although science has developed considerably since the book was published, challenges still remain, from designing a breathable habitat to growing nutritious food. But there’s another issue that a NASA research project called the Center for the Utilization of Biological Engineering in Space (CUBES) has been working on since 2017, one that is as essential to the long-term success of an off-planet human settlement as air or food: treating illness.

It’s a tricky problem that doesn’t have an easy answer. What about packing the shuttle full of medicine? This might seem like a realistic solution at first glance, but astronauts can’t know in advance all of the ways they could get sick. There are some known risks to sending human life to Mars, such as the effects of the planet’s lower gravity on bone density and muscle mass or potential exposure to cosmic radiation as astronauts leave the protective cover of Earth’s atmosphere. But packing medicines for every contingency would be expensive and take up precious cargo space.

Nor could astronauts depend on timely shipments from Earth, due to the long distance between our planet and Mars. The spacecraft that have landed on Mars have taken the better part of a year to get there. Perseverance, the most recent robotic rover sent to Mars on July 30, 2020, is expected to land by the time you read this: more than 200 days after launch. That’s far too long to deliver urgent, lifesaving medications or supplies.

Synthetic solutions

Rather than sending astronauts into space with a costly and finite stock of medicines, scientists have approached the problem a little differently. What if astronauts could manufacture on Mars what they need?

“If we could have programmable life make things for us, then we don’t have to account for every possibility before we go, because life is programmable in ways that other things aren’t,” says Adam Arkin, director of CUBES. Arkin has spent his career investigating how, as he puts it, “to build things out of life,” by developing more sustainable biomanufacturing systems. Mars presented an ideally challenging environment for these aspirations; after all, it’s an unpredictable, extreme environment where humans must, by necessity, expend every resource available to them. “If we could build something that could be grown, essentially, as a factory, we could reduce the costs and increase the efficiency and resiliency once you [are on Mars],” he says.

Programmable plants

The “factories” Arkin envisions could include technology to program plants, such as lettuce and spinach, and microbes, such as spirulina, to produce stable drug therapies. One of four divisions in CUBES, the Food and Pharmaceuticals Synthesis Division (FPSD) is exploring a few different methods to best leverage naturally occurring organisms for pharmaceutical production. For example, there is the seed stock model: Seeds from a plant that has been genetically modified to produce a target molecule (a medicine), are sent on the spacecraft with the astronauts. Then, once a human colony has been established on Mars, settlers could grow these plants and either directly consume the plant to get the medicine, or extract the medicinal component, purify it, and inject it as we do with many drugs on Earth.

In order to produce these plants, the FPSD is using an older technique called agrobacterium transformation, a process in which bacteria called Agrobacterium tumefaciens is used as a vehicle to deliver a DNA expression system into the plant genome. By introducing new DNA into the target plant, scientists are able to induce the plant to produce a therapeutic protein that it wouldn’t otherwise. Another method involves synthesizing genes that code for whatever drug an astronaut may need on Mars, or selecting from a kind of DNA library, then injecting genes directly into the plant.

“When you’re talking about synthetic biology, one of the powerful things about it is you can synthesize DNA for a variety of purposes. So, having a gene synthesis capability on-planet I think would be a very valuable tool,” says Karen McDonald, head of the FPSD and a professor of chemical engineering at the University of California, Davis. Once synthesized, the genes could be directly introduced into plants on demand using a tool called a gene gun, a ballistic device that shoots particles of DNA onto the surface of a leaf with such force that it penetrates the plant’s cell wall, allowing the genetic material to be introduced into the organism.

What does this look like in practice? One of the division’s main projects is to produce a protein peptide in lettuce plants that could be used to treat osteopenia or osteoporosis using agrobacterium transformation. By propagating the plant through multiple generations, researchers will be able to select for the lines that produce the most stable amounts of the drug from one generation to the next. They’re also looking at other leafy greens, such as spinach, as potential platforms for drugs. Not only have these plants been frequently used in NASA experiments, they also have a very high harvest index, meaning that most or all of the plant can be consumed for food, which makes them likely candidates for a mission to Mars.

The next planet

“As engineers, we work with designing systems under constraints,” McDonald says. “But the constraints that we are dealing with here on Earth are nothing like the constraints that you might have in a Mars mission.” Her team faces two connected challenges: perfecting methods to cheaply and efficiently extract from plants and purify compounds that are safe for the astronauts to inject, and determining how much of the medication would actually make it into the bloodstream. McDonald says astronauts may need to bring some diagnostic equipment to ensure the medicine is purified and safe to consume.

Although CUBES has its sights set on the stars, this work has important questions for life on Earth, too. Arkin says it’s unlikely — and ill-advised, from a health and safety standpoint — that this technology will eliminate the large-scale production of pharmaceuticals here on Earth. But that doesn’t mean that CUBES’ research doesn’t have the potential to radically disrupt the way we eat and grow things here, particularly in the coming decades as climate change intensifies, the global population increases, and our natural resources continue to diminish.

“[CUBES] was about the idea that, yes, Mars is the next planet we might visit, but our planet is changing at such a high rate that we have to deal with the ‘next planet’ here as well,” Arkin says. “And if we can build an autotrophic self-building factory that can support 10 people for food and fuel and pharmaceuticals and building materials, from carbon dioxide and light and waste, that would be a huge benefit to mankind everywhere. It would set us up for our next planet here.”