Key Takeaways:

- Perseverance's mission represents a significant advancement in Mars exploration, directly seeking evidence of ancient life (3-4 billion years old) using a sample return strategy, unlike previous missions which focused on extant life.

- The rover's key capabilities include a coring drill for collecting rock samples in titanium tubes for return to Earth, advanced spatially resolved analysis instruments (PIXL and SHERLOC) for detailed chemical mapping, and the ability to identify lifelike chemical compositions and structures.

- The Jezero crater landing site was chosen due to its history as a lakebed with a river delta, offering diverse geological environments and potentially preserving signs of ancient life, situated strategically between older and younger Martian geological formations.

- While Perseverance will analyze samples in situ, definitive confirmation of Martian life will require detailed examination of returned samples on Earth, using techniques such as light microscopy and spectroscopy for higher resolution analysis of potential microbial structures (e.g., stromatolites).

The first era began in 1964 when Mariner 4, the first successful Mars spacecraft, flew by the planet and sent back images of a seemingly barren, cratered, Moonlike world. To a public raised on fanciful tales of Mars as harsh but habitable land, the views came as a shock. Subsequent missions painted a more varied, nuanced portrait of the Martian environment, raising hopes for the 1976 Viking missions. Two landers dug into the red soil and tested it for signs of life — but they came up empty. Those results closed out Era One with a disappointing message: Mars is a dead planet.

Over the next two decades, planetary scientists began to realize that the Viking experiments were naive, based on insufficient knowledge about the geology and chemistry of Mars. The second Mars era began in 1996, when NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor entered orbit and the little Sojourner rover began rolling across the surface. The goal this time was to develop a deep understanding of the planet’s history and evolution, with an eye toward finding out if life ever took hold there, even if it died out billions of years ago. Over time, spacecraft from India and the European Space Agency (ESA), and now China and the United Arab Emirates, joined the effort.

Perseverance is the culmination of Mars exploration, Era Two. For the first time, a rover will explore the Martian surface not just for local study, but to collect samples for return to Earth. All the power of the world’s research laboratories will be unleashed on them. The results of those studies could finally uncover the long-sought signs of alien life, or could greatly strengthen the case that Mars was never the living planet we hoped it was.

Scientific curiosity, international competition, and private explorers like Elon Musk guarantee that Era Three of Mars exploration will happen. But what that era looks like will depend profoundly on what Perseverance finds as it samples the landscape around Jezero crater on Mars. You can watch the landing live (with speed-of-light time delay!) via NASA’s online livestream starting at 2:15PM EST on February 18. After touchdown, at 8PM EST the same day, the National Geographic Channel will offer a deep look at the mission’s backstory in a two-hour documentary, Built for Mars: The Perseverance Rover.

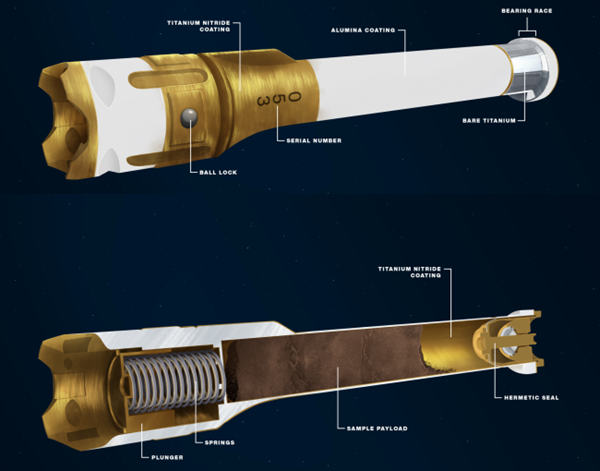

Even if the landing unfolds flawlessly, we won’t know the true meaning of Perseverance’s journey until later this decade, when NASA and ESA mount a mission to return its 15-centimeter-long sample tubes to Earth. I spoke with Ken Williford, deputy project scientist on Perseverance and one of the voices in Built for Mars, about the mission’s goals, along with his greatest hopes (and fears) about what the intrepid robot might find. A lightly edited version of our conversation follows.

Perseverance superficially resembles its predecessor, NASA’s Curiosity rover, but I know that appearances are deceiving. What’s fundamentally different about this mission?

Great question. The way we’re moving the science forward with Perseverance is that we’re directly seeking the signs of ancient life and, as such, directly looking for evidence of life beyond Earth in a way that’s more serious than any mission since Viking in the mid 1970s. Or more direct is maybe a better word. That’s not a knock on Curiosity. I myself worked on that mission and loved it; it was very successful. We’re standing on the shoulders of giants, but also taking the next step.

The thing that’s so exciting to me as an astrobiologist is to get the chance to be a part of a mission that is directly and explicitly tasked with looking for evidence of life beyond Earth. The key distinction between us and Viking is that Viking was looking for signs of extant life, organisms that are currently alive or recently deceased, whereas we are doing something very different, looking for signs of ancient life, very ancient life, three to four billion years old.

I would say the biggest thing that sets Perseverance and Curiosity apart in terms of the hardware is our sampling system. Mars 2020 [the original name of Perseverance] is the first step in what would be a campaign of missions required to select and collect samples, store them on the surface of Mars, and then eventually get them back to Earth for study in Earth-based labs.

That’s called Mars sample return. It’s an idea that’s been around for quite some time, and we’re only now standing on the threshold of really beginning that process in earnest. We have a new science instruments, as you said, and we’re going to use those instruments to choose the locations in our exploration area, in and around Jezero crater [the Perseverance landing site on Mars], that have the best chance to have preserved signs of ancient life. We’re also looking at planetary evolution: How did Mars form and evolve as a planetary system? How is it similar or different to the path that Earth took as a rocky planet?

We’d like to address those questions from the surface with our instruments, but we’ll also take samples with a coring drill. That’s another big difference between the two missions. Curiosity’s drill generates powder that it takes onboard the rover to instruments inside the rover to analyze right there on Mars. Our drill instead makes cores of rock about the size of a piece of classroom chalk, seals them in titanium tubes that are then placed on the surface of Mars. Eventually, another mission picks them up and gets them into orbit. Then a third mission grabs them and flies them back to Earth for all that science that happens later, back in the Earth-based laboratories.

How will you pick out the exceptional samples that say to you, “Oh, this is something we want to take a closer look at on Earth?”

We get very specific like that, looking for very specific properties of individual samples. We also take a broader view. One of the main motivating factors is our interest is to build a diverse set of samples, a geologically diverse set of samples. The science team has spent many years on that. Other scientists have been using data acquired from orbit. Based on those images and spectra from orbit around the landing site, we’ve built geologic interpretations of how that area evolved through time. The crater was formed by a big impact, a river floated into it, filled the crater with a lake. There was a delta that formed, so the lake had an ancient shoreline, it had an ancient deepest middle part of the lake. It had all these little micro-environments.

The area outside Jezero is something we hope to explore eventually as well, the crater rim itself, the history of that impact. We’d like to understand the rocks outside Jezero that were there before the crater formed. Those rocks are on the western edge of a much, much larger crater called Isidis that we think could’ve only formed very early in Mars’ history. We want to visit all those different rock units and collect samples, because they each contain an important piece of this grand puzzle that we’re trying to put together, which is really about Mars’ history as a system. Most exciting to me is this question, did life ever emerge on Mars, and if so, how widespread was it?

Are there specific chemical or structural signatures that will tell you which rocks are the most promising ones for getting those answers?

What we look for in individual samples, specifically when we’re targeting signs of ancient life, is lifelike chemical compositions and lifelike shapes, especially when they occur together. We’ll observe shapes with our cameras that are all over the rover. We’ll observe compositions with our spectrometers, of which we have many aboard the rover. We’re looking for lifelike chemical elements in the rocks — inorganic minerals and organic matter, and if there’s organic matter what type might be there.

A big technological advance in the instrumentation with Perseverance is this ability to do what we call spatially resolved analysis. We have mapping instruments which, as opposed to measuring the bulk chemistry of something that’s kind of averaged over a larger area, maybe a cubic centimeter or a cubic inch if you like, they’re rastering a beam, in the case of the PIXL and SHERLOC instruments. These two instruments have a beam that is about the width of a human hair, about 100 microns, and it scans that beam over the area to get a map of chemical composition.

Not individual cells, unless the cells are very large, and we don’t expect to see something like that. In fact, one of the main reasons to get the samples back to Earth is so we can use light microscopy and spectroscopy to get higher spatial resolution, even down to nanometer-scale resolution. With spatial resolution like that, we can distinguish individual fossil cells quite well. There are many examples of them on Earth. Some of the oldest sedimentary rocks on Earth have fossil bacteria in them.

What we can see on Mars with Perseverance is larger-scale structures that can be formed by single-celled organisms, like microbial mats. We absolutely can see things at that scale. Those are almost meta-shapes formed by those little cells.

Those structures can be really ambiguous, though. The controversy over the life-like structures in the Mars meteorite, Allan Hills 84001, is still unresolved 25 years later.

Yeah, absolutely. We think about the Alan Hills meteorite a lot. It launched a lot of interesting science and in some sense was really responsible for the expansion in the field of astrobiology. The funding that paid for PhD work may well not have existed had it not been for that. It set into motion the approach I just described, looking for both lifelike shapes and lifelike compositions when they occur together. I think some people oversimplify the history of the meteorite [and the reported claim of fossil life from Mars]. There was a lot more to that paper, if you go back and look at the details.

I’m going to give away my age and let you know that I was at that press conference in 1996.

Really? Nice!

There’s still a sensitivity among scientists who work in astrobiology to interpreting shapes alone [as indicators of past life] in the absence of compositional information. Humans are fantastic pattern-recognizers. We see things that aren’t there all the time. I’m looking out my window right now at shapes I can see in the clouds and that sort of thing. So we have to be vigilant against fooling ourselves, but at the same time, if we completely shut down our visual sense and say, “Don’t believe what you see,” then we’re really at risk of missing big things. It’s one of the most interesting challenges we face with Perseverance: How do we be stay open to interesting things on Mars without unduly fooling ourselves?

Let’s get into it, then! What might a truly meaningful mineral or structural relic of ancient life look like?

There are a number of minerals that we often find associated with signs of ancient life on Earth. Carbonates are a big one. On Earth, seashells are made of carbonate minerals. We don’t expect to find large, complex animals of the kind that form seashells on Mars, but even the oldest stromatolites [sedimentary structures associated with bacteria] are formed from carbonate minerals that have later been partially silicified. Porous fossil microbial mats contained carbonate minerals and some fluids with dissolved silica flowed into them. In some cases, the silica precipitated out, replaced some of the materials in the stromatolite, and led to it being preserved in a way that it otherwise might not have been, as microcrystal and quartz.

Then there are sulfate and sulfide minerals, sulfur-bearing minerals in both the oxidized and the reduced phases. One way to look at it is, you could boil it down to the chemical elements that you’re interested in. The core list for astrobiology are the “CHNOPS elements” [carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorous, and sulfur] and we look at all the minerals that bear those elements. We have carbonates, sulfates, phosphates, and so on. There are many others. Any case where you can get redox couples, so oxidation and reduction chemistry transforming something like a sulfate into a sulfide, any chemical reaction like that is something that a microbe can make its living from.

How much of Perseverance’s focus is on planetary geology versus astrobiology? And is there a tension between the two goals?

Well, geochronology lies in the realm of planetary evolution, understanding what the interior of Mars is made of and how that’s evolved over time. But these big, broad questions are also critical to astrobiology; all of these processes enable and regulate the habitability of a planet. How did the non-living systems on the planet evolve and change in a way that caused the planet to be habitable, or that caused that habitability to collapse?

Then again, the best samples for geochronology may not be best for preserving signs of life. A natural dynamic tension exists there. The way I think about it, coming more from the astrobiology side, is just as I said: All that stuff is completely critical to the signs of life and understanding their context. It’s all just big, beautiful science as well.

Well, it very clearly was once a crater lake. There’s an ancient river channel flowing into it from the northwest. Less obvious, there’s an outflow channel in the northeastern corner of the crater. Then there’s this big, beautiful delta. If you find a delta at the end of a river system inside a basin like a crater, it says there was a standing body of water here that was met by a flowing body of water. In this case, a lake is met by a river, and the river is capable of carrying all that entrained sediment because there’s energy of flow. Then when it hits the standing water, the energy drops and the sediment drops out in a big pile, just like where the Mississippi Delta meets the Gulf of Mexico.

So that’s Jezero itself, but it’s zooming out to the broader region around it that really led us here in the first place. The crater sits within a region that offers access to not only the earliest interval of Mars’ history but a younger interval where we have the Syrtis volcanic province [when the huge Martian volcanoes erupted]. Jezero is situated between Isidis to the northeast of Jezero and the Syrtis volcanic province to the southwest. Materials from that volcano would’ve been interacting and the impact of that volcanism on the Martian environment would have been recorded to some extent in the rocks around Jezero.

Is it possible to deduce how long ago Jezero crater was a lake, and how long that wet period lasted?

Our best estimate so far for the age of the Isidis impact, which has to have been earlier than the Jezero impact, is about 3.9 billion years ago. We are not about the absolute age of Jezero, however. The estimates range as old as 3.8 billion to a good bit younger, but we’re quite confident it’s in the period between three and four billion years ago. Interestingly, that is the time when we find the first evidence of life on Earth.

Perseverance is bringing along an experimental helicopter called Ingenuity. Will it help you locate interesting places to explore?

Ingenuity has a well-defined mission that it plans to execute over 30 sols [Martian days] with five flights of increasing complexity. The mission there is to demonstrate that that flying technology can work on Mars. It would be really powerful in enabling future helicopters that could land and be a major component of the science exploration. We’re all rooting for the team and can’t wait to see the images that result, but it’s not a component of our science mission planning.

What makes Jezero crater such a significant place to go prospecting for evidence of ancient Martian life?

Jezero offers clear set of environments and sub-environments, all the different areas within the ancient crater lake. We can very confidently say, if we go there and we do our job and we collect a diverse set of examples that have been very well characterized and we bring them back — if we do not find any evidence of life in there, that tells us something quite significant. This is a clearly habitable environment early in Mars’ history. If life had emerged on Mars, it seems very likely that it would’ve left signs in an environment like Jezero crater.

That’s quite a powerful statement! If we bring back samples from Jezero crater and find no signs of life, what then? Would the next step be to do a deep drilling mission on Mars?

Yeah, I think a deep drilling mission or, more broadly, a mission that looks whether there are still habitable environments on Mars today. We believe, based on what we know, that any modern life would have to be confined to the subsurface, maybe the quite deep subsurface, so deep drilling might be required.

Part of the way I look at this is that it seems we’re on a path toward human exploration of Mars in perhaps the not too distant future. This is something I’m very excited about. The idea of seeing a human being on Mars and having that human come back and relay her experience to the people of Earth and show the images and everything… Just to be our representative there and to have the planet seen directly through human eyes, that’s really inspiring to me.

There’s a lot of connections and implications between human exploration of Mars and any effort to understand whether Mars might currently be inhabited. Those two efforts are linked, first of all, from the side of planetary protection. The Mars 2020 team spent a lot of time and effort building a system to avoid contamination of the Martian surface by Earth organisms in the interest of preserving Mars as a pristine environment and preserving our ability to look for evidence of life on Mars, extant life. When you bring humans, it’s very difficult to meet the stringent planetary protection requirements [preventing contamination] that are the subject of international agreements.

Another really interesting connection is that we have this instrument on our rover called MOXIE. It’s a type of experiment called in-situ resource utilization, going to an environment and using something that’s there to be useful to your exploration. In this case, MOXIE will be generating oxygen from Martian CO2. More broadly, if you land humans on Mars, what resources are they going to be able to use there? A key resource is water, so landing where there might be access to water for humans is a big thing that they’re thinking a lot about.

In some ways, then, won’t human astronauts make the search for life more difficult?

Well, the places where you find water are the places you’d be most likely find any life, so that’s an interesting connection. I’m just looking forward to seeing how it all goes. Right now, we’re focused on the robotics side and both protecting Mars from undue contamination by Earth organisms. Quite critically, and for the first time, we’re also concerned with being part of a larger system enabling future missions to get the samples that we collect back to Earth. We have to do it safely, such as that there is no contamination of Earth by any Martian material, so that the container that holds those samples is opened in an extremely secure environment and assessed for Earth safety prior to all the great science will happens after those samples make their way out of the secure facility.

Well, honestly, my mind doesn’t go much to thinking about in that way! It would be fantastic to find something so incredibly exciting that we’re jumping up and down thinking that we maybe have evidence of life on Mars. But right now my mind is just so focused on the present concern and with building a strategic structure for a mission, so that whether or not we ever find any evidence for life on Mars, we put together an absolutely phenomenal set of samples. It helps, psychologically, to keep our focus. It’s not about assuming the worst, it’s just saying, “No matter what, we’ll learn a lot from these samples here.”

Understood. But still, you must have considered what kinds of evidence would get you jumping up and down.

Yes, we’re keeping our eyes peeled for the types of things we look for when we’re exploring the Precambrian rocks on Earth, where life is confined to stromatolites and things like that. We’re looking for structures like that. I can stop and put together a scenario that says we find something like what you see in Australia, called the Mickey Mouse-ears stromatolites.

Excuse me, did you say “Mickey Mouse”?

The canonical [non-biological] stromatolite is a layered dome. When you see it eroded off into a flat, horizontal plane, you see a bunch of concentric circles. Many minerals precipitate that way. But when life is involved, often the layers are of different thicknesses, and they can pinch and swell and wrinkle. Branching is something that we see in life expressed all over the place. You’ll see two domes growing out of one, like the ears of Mickey Mouse on his head. The specifics of the shape are very difficult to impossible to explain without biology. It would be exciting to find that in a Mars rock.

If you see a Mickey Mouse mineral structure on Mars, what’s the next step as you try to nail down, once and for all, the evidence of life?

Even on [ancient] Earth, most of what you find is ambiguous. Next you look at the composition, but you find compositions that also have some complexity to them; maybe there’s two different chemical compositions in alternating layers. Where it would start to get really profoundly exciting is if we start to see organic matter concentrated in certain layers and not in others, and if it’s all organized in some sort of wrinkly, layered, dome-shaped structure. These are evidence of ancient life we can observe on Earth today, and they’re the closest analog to the most powerful observations we could imagine making on Mars.

The chances of us finding that needle in the haystack, that’s another matter. It gets back to the importance of bringing samples back home. There are areas on Earth where you might have Mickey Mouse ears stromatolite over here but maybe you never see that. But if you take a sample that’s anywhere near that thing, it’s going to have some [chemical or microscopic] expression of life within it, even though it won’t be obvious to you in the field. It won’t show up for you until you get it back to the lab, do a bunch of careful sample preparation, and take it through a number of different analytical techniques.

That’s more of the scenario that I guess I would say is even optimistically likely.