In just a few short weeks, NASA’s Perseverance rover will begin to survey the area “in person.”

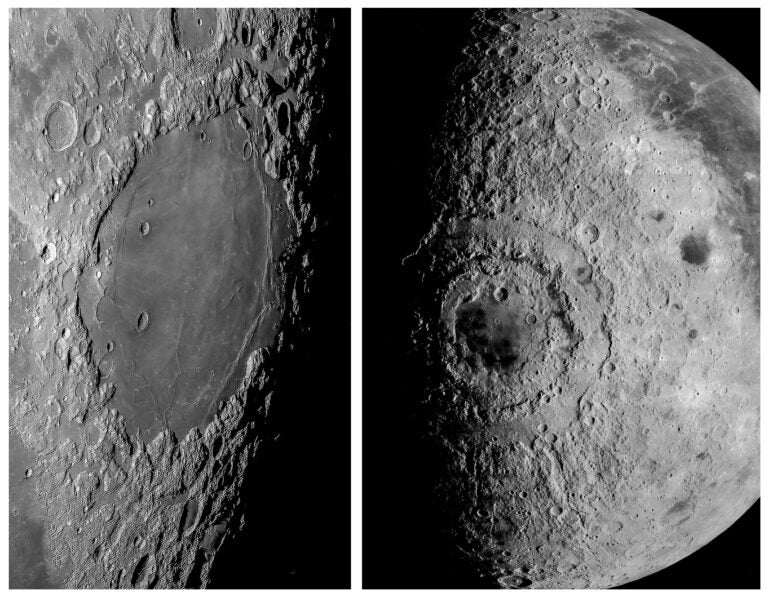

Jezero Crater: A varied landscape

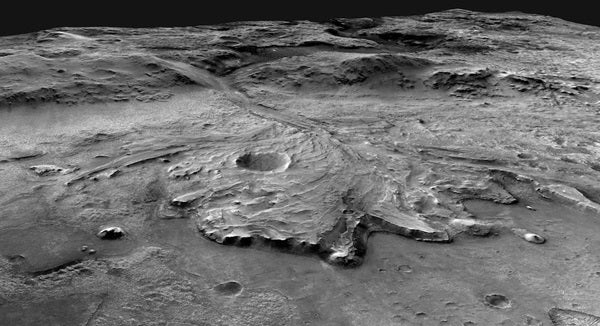

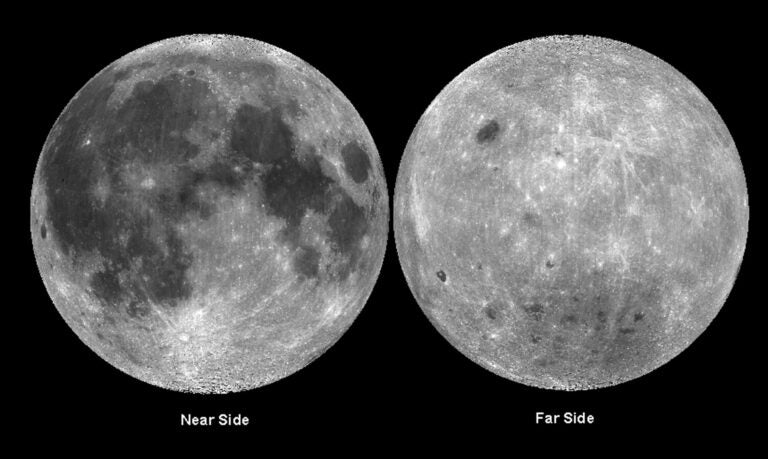

Based on spacecraft imagery, researchers think Jezero Crater was once home to a lush river delta. Deltas form as rivers drop sediment into relatively placid, larger bodies of water — like lakes and oceans. And that process of deposition creates a number of varied environments.

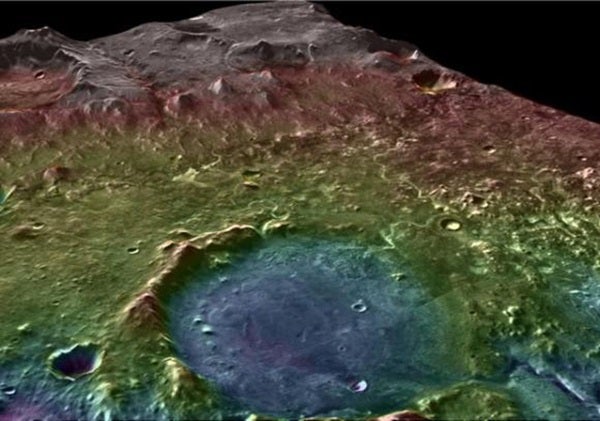

When Mars was still young and wet, and life was likely just taking hold on Earth, Jezero Crater was home to a 1,600-foot-deep (500 m) lake. Scientists think a network of rivers probably fed into this site, making it a prime place for life to have evolved on the Red Planet.

And that’s why NASA chose to explore it. The idea of a persistent wetland on Mars was enough to convince astronomers to select Jezero Crater as the landing site for NASA’s Perseverance rover, as well as its companion the Ingenuity helicopter.

Jezero Crater — named after the small town of Jezero, Bosnia — spans roughly 28 miles (45 kilometers), giving the rover plenty of room to roam. (More than a decade ago, the International Astronomical Union, the organization responsible for naming planetary bodies, decided to name a number of scientifically important Mars craters after small towns around Earth.)

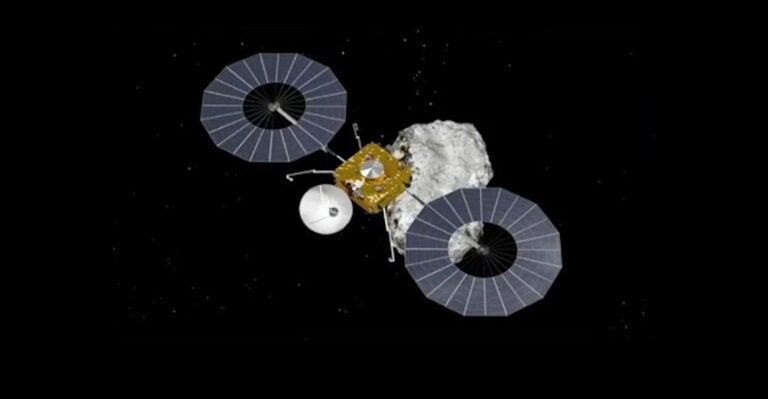

Perseverance is a nearly car-sized rover that’s designed to characterize Mars’ geology and study its ancient climate. Along the way, it will hunt for signs of ancient alien life — specifically, microbial life — and collect soil and rock samples that will eventually be sent back to Earth for further study at world-class laboratories.

And Jezero Crater provides the perfect place for Perseverance to pick up an array of promising samples.

A long path to landing at Jezero

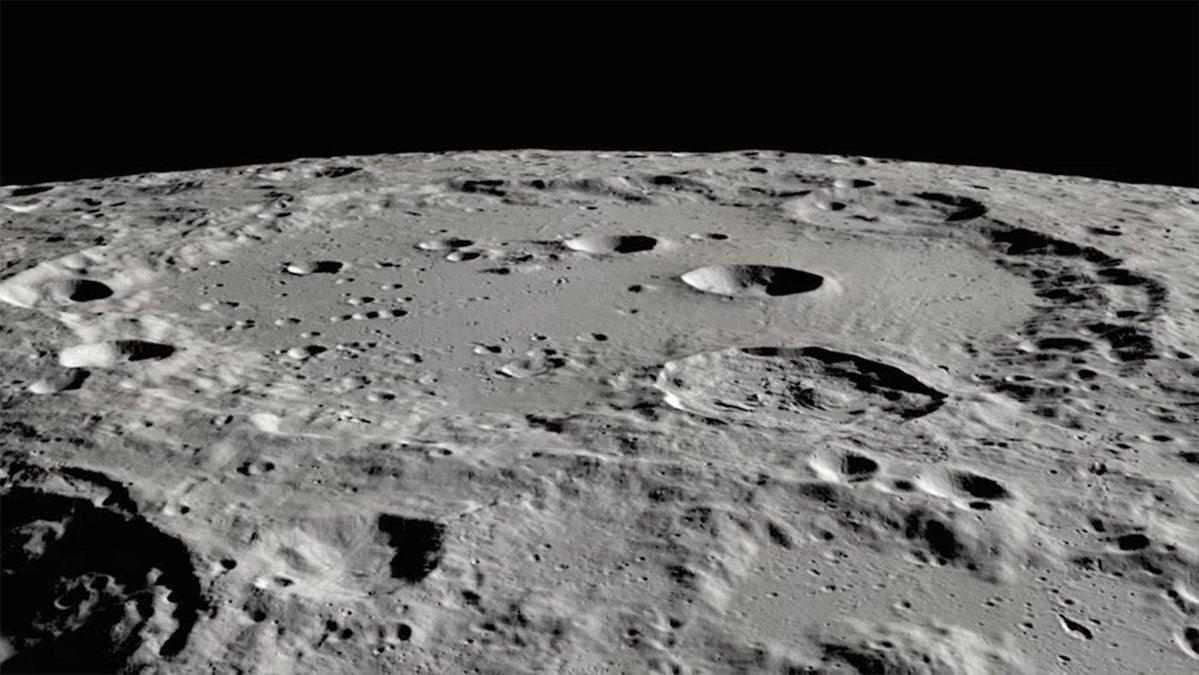

In 1976, NASA’s twin Viking landers touched down on Mars within just a few months of each other. They didn’t have wheels to roam the surface, yet the missions still changed how astronomers looked at Mars.

The Viking landers found clear signs of river valleys, wet weather, and erosion. Plus, a soil experiment on Viking even found tentative evidence of microbial life. Scientists later determined that was a false detection, but taken together, the Viking missions’ discoveries served to build excitement for better understanding Mars’ ancient climate. And that excitement help spur further exploration.

In the decades since, NASA has sent a handful of rovers to Mars to build on those findings. And each one has been more sophisticated than the last.

The latest robotic roamer before Perseverance, NASA’s Curiosity rover, landed in 2012 with the goal if determining “if Mars was ever able to support microbial life.” The robot traversed more than a dozen miles within Gale Crater, a former lakebed, providing new insights into Mars’ ancient climate, current geology, and watery past.

That’s helped whet astronomers’ appetites for exploring other ancient sites on Mars that once held water. So, in preparation for Perseverance’s trip, astronomers considered some 60 candidate landing sites over the course of several years. Different groups of researchers had their own ideas about which location was best, and the landing site debate was often contentious. But as it played out, it became increasingly clear Jezero Crater has once been a vast wetland.

A flowing river delta

In 2015, research published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets showed that now-dry Jezero Crater was home to water twice in Mars’ past.

The scientists used satellite observations to conduct what geologists call a “source to sink” analysis, where they trace a variety of minerals in the martian watershed back to their original source upstream. For example, clays, which form in the presence of water, seem to have been picked up from surrounding areas and dropped into the crater lake by flowing water.

Interestingly, the team’s analysis showed the Jezero Crater served an active watershed during two separate time periods before the water dried up around 3.5 billion years ago, upping the chances of martian life once gaining a foothold. The water was likely so high at one point that it spilled over the crater walls. A number of papers since then have backed up those findings.

Astronomers now envision Jezero Crater as a dynamic system, with water flowing both in and out over long periods of time in the past. NASA would love to sample the rocks at the center of the delta, where the water would’ve been the deepest. The muddy deposits there could preserve a record of organic matter, the way similar rocks do on Earth. And perhaps the most intriguing possibility is that Jezero Crater may have once been home to microbial mats, like pond scum forming at a lake’s edge. Certain minerals could’ve preserved that pond scum, forming what scientists call stromatolites — a kind of layered rock that’s essentially a fossil.

The Perseverance rover will keep a careful eye out for this kind of Mars fossil deposits. And — as it pokes, prods, and samples the soil — the rocks in Jezero Crater should offer new clues about whether life once existed in the early, wet days on Mars.