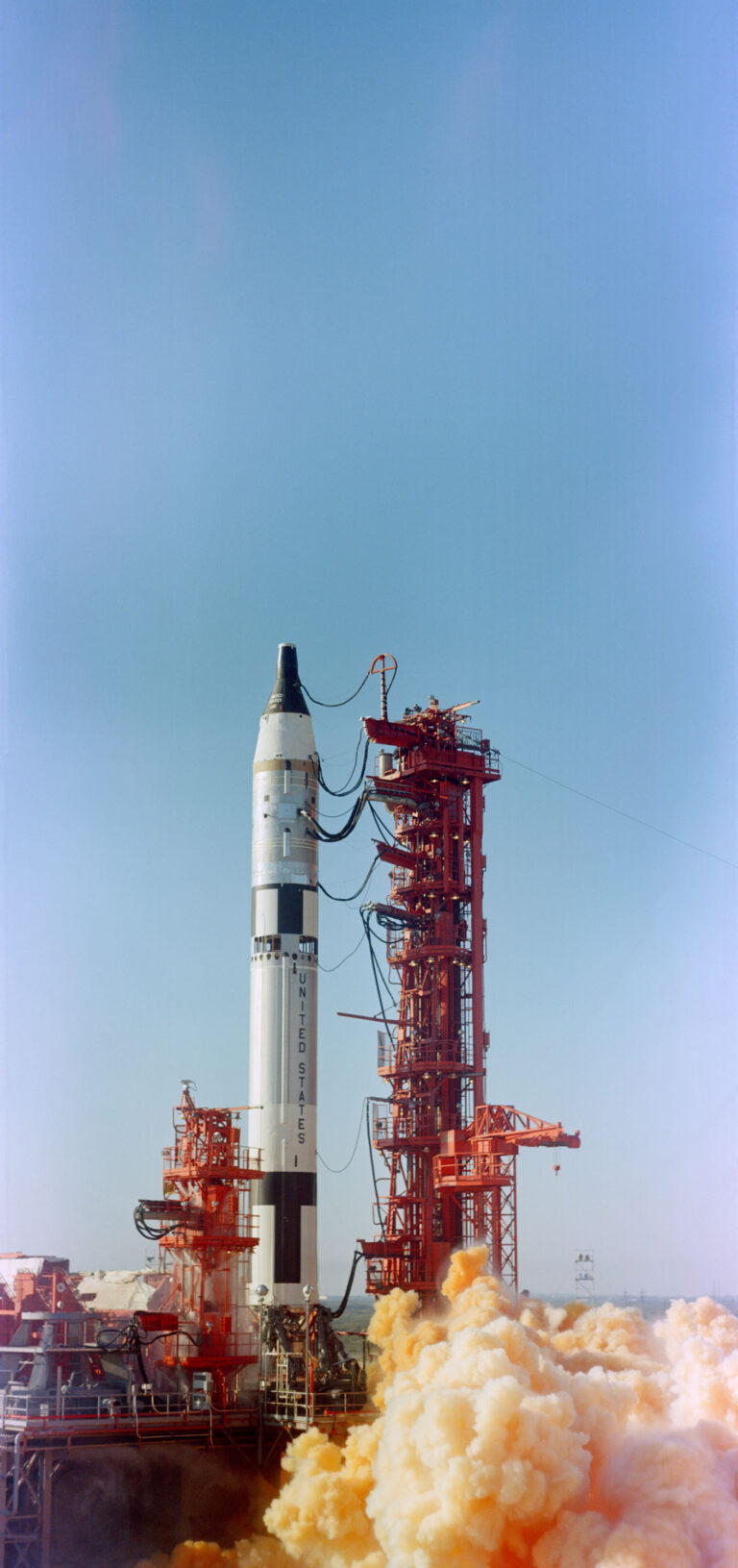

NEAR Shoemaker — NASA’s Near-Earth Asteroid Rendezvous mission, a name later modified to honour planetary scientist Eugene Shoemaker — may now be far from Earthly companionship. But over the course of its life, it’s had frequent run-ins with the romantic holiday. The spacecraft launched during Valentine’s week in 1996, reached its destination during Valentine’s week in 2000, and it landed during Valentine’s week in 2001.

And as if that were not enough, the target of NEAR Shoemaker’s insatiable desire was none other than the stony asteroid Eros, a Staten Island-sized lump of primordial silicate-rich rubble named after the ancient Greek god of love.

A brief history of asteroid Eros

Situated 120 million miles (190 million kilometers) away, Eros was not the first asteroid to gain fleeting human — or at least robotic — company. NASA’s Galileo probe previously surveyed asteroids Gaspra and Ida a decade earlier on its way to far-off Jupiter. But with NEAR Shoemaker’s trip, Eros became the first asteroid to host an artificial satellite in orbit, as well as the first asteroid to host a probe on its surface.

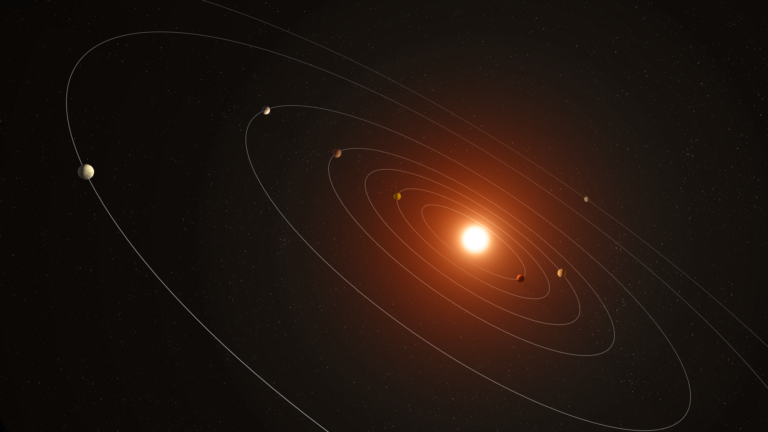

Untold trillions of asteroids exist throughout our solar system, chiefly in a doughnut-shaped belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. They are thought to not only be the remnant building blocks of the planets, but also may furnish clues about how Earth evolved, and perhaps how the earliest murmurings of life arose on the tiny blue marble that we call home.

More recent data suggests that in the far future Eros might become an ‘Earth-crosser,’ too, which would make it a possible impact risk. And if Eros turns out to be an Earthly threat in the future, it would be a major one. In fact, Eros is several times bigger than the object thought to have created Chicxulub Crater, which obliterated most of the non-avian dinosaurs some 66 million years ago.

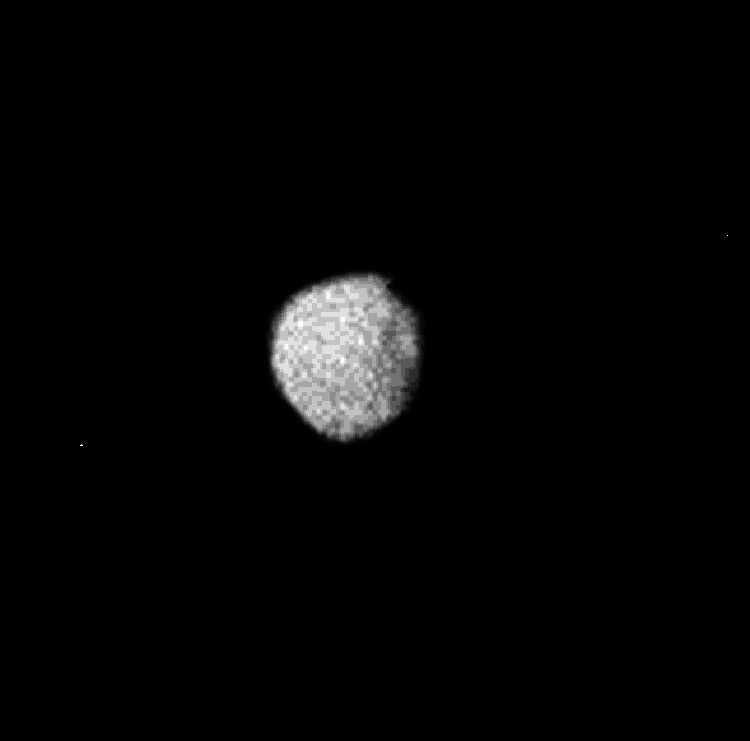

Well known to professional and amateur astronomers alike, Eros is by far the best-observed near-Earth asteroid. It is some 20 miles (32 km) long, about 7 miles (11 km) thick, and has a shape similar to fat banana.

NEAR Shoemaker’s busy trip to Eros

To reach asteroid Eros, NEAR Shoemaker began its 35-month cruise on February 17, 1996. And along the way, the spacecraft became the first solar-powered probe to fly beyond the orbit of Mars.

NEAR Shoemaker came equipped with X-ray and gamma-ray spectrometers, a near-infrared imaging spectrograph, a multi-spectral camera, a laser range finder, and a magnetometer. In June 1997, it glimpsed asteroid Mathilde from afar, revealing a slowly-rotating carbon-rich object that’s as dark as fresh asphalt. Plus, the probe found that Mathilde sports yawning craters, which have since been named for terrestrial coal fields.

If Mathilde was Shoemaker’s appetizer, the main course was unequivocally Eros. To pick up an added push to get there, NEAR Shoemaker returned briefly to fling around Earth, whose gravitational influence firmly boosted the craft toward its final destination.

But during the final leg of NEAR Shoemaker’s trip, without warning, cruel fortune almost stalled the mission in its tracks.

Shoemaker survives a shake up

A few weeks before arriving at Eros, the probe attempted to fine-tune its inbound trajectory. However, its engine spluttered and died after a few seconds, causing it to begin to tumble.

Mission controllers were eventually able to stabilize the probe. But it was still “the longest 27 hours of my life,” lamented project manager Tom Coughlin of Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. The spacecraft had survived — yes. But that not-so-brief brush with calamity eliminated all hopes of entering orbit around Eros by January 1999.

Fortunately, the delay did not mean that an orbital mission was out of the question, and efforts were already underway for another attempt the following year.

Finally, despite suffering a computer reset, weathering the hyped Y2K software bug, and enduring another far-from-perfect engine firing, on the first Valentine’s Day morning of the new millennium, NEAR Shoemaker slipped into orbit around a celestial object named after the god of love.

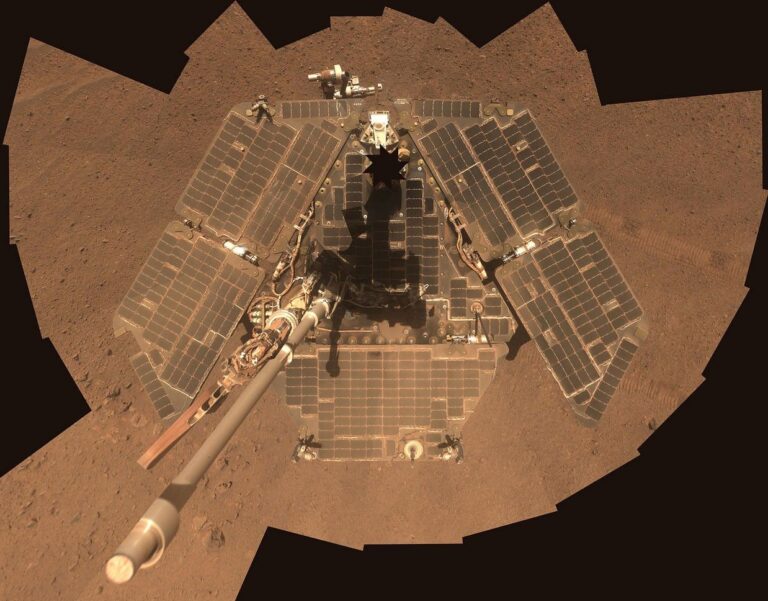

Shoemaker sets up shop on Eros

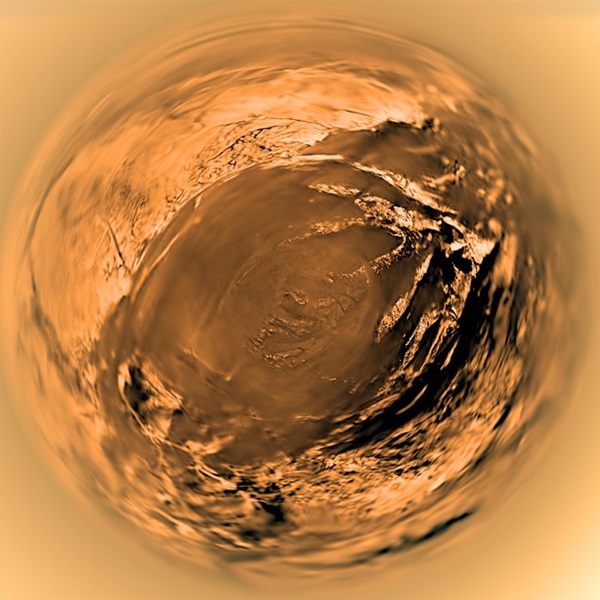

Over the next few months, NEAR Shoemaker circularized its orbit and approached Eros, coming within about 22 miles (35 km) of the asteroid’s surface. During this time, it globally mapped the ground and examined peculiar ridges, square-shaped craters, boulders, surface grooves, and trough-like depressions. Then, by January 2001, as it nearly brushed the edge of Eros at an altitude of just 1.7 miles (2.7 km), hopes of a soft landing on the asteroid’s surface entered the realm of possibility.

“This is a bonus,” mission director Robert Farquhar of Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory cautioned at the time. “The descent maneuvers are the most complicated we’ve ever tried, and because the spacecraft is an orbiter that wasn’t designed to land, there is only the smallest chance it will survive on the surface of Eros.”

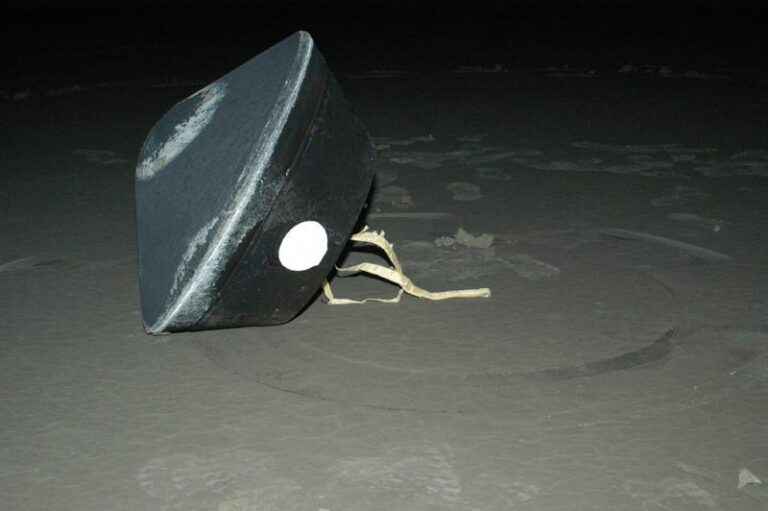

Over the course of 4.5 hours on February 12, 2001, NEAR Shoemaker executed its nail-biting descent with its camera pointed down to reveal the steady, inexorable approach of the surface. Landing, when it came, was surprisingly gentle, touching down at about 4 mph (6.4 km/h). NEAR Shoemaker also came to rest remarkably close to an interesting saddle-like depression called Himeros.

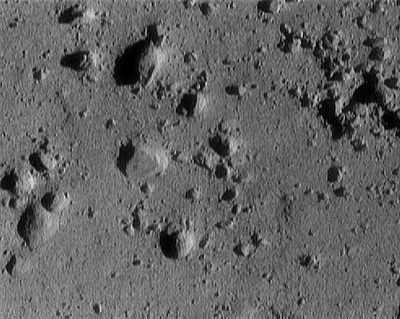

As the probe floated silently towards Himeros, it scrutinized this Key West-sized surface feature, which looked like part of a large impact crater. The last photograph of the site was taken less than 400 feet (120 m) above the surface, revealing a patchwork of pebble-strewn terrain, fragmented boulders, and a dust-filled crater the size of a football field. But Farquhar’s caution was well founded, for the landing was indeed the spacecraft’s curtain call.

NEAR Shoemaker finally went radio quiet on February 28, 2001.

Since then, several other missions — NASA’s Stardust, New Horizons, and Dawn; Europe’s Rosetta; and China’s Chang’e-2 — have gone on to examine near-Earth objects, main-belt asteroids, and trans-Neptunian bodies. And just last December, Japan’s Hayabusa-2 even returned samples from asteroid Ryugu to Earth, which scientists are now eagerly inspecting. Also chomping at the bit is NASA’s OSIRIS-Rex mission, which last October sampled asteroid Bennu. The mission aims to return those specimens to Earth in September 2023.

And there’s plenty more to come, too. In October of this year, NASA’s Lucy mission will set off on a decade-long trek to visit a half-dozen Jupiter-trailing Trojan asteroids. Next year, China’s ZhengHe spacecraft will fly a sample-return mission to the rapidly rotating near-Earth asteroid Kamo’oalewa. And also in 2022, NASA’s Psyche will head for a metallic asteroid of the same name.

It has been 20 years since NEAR Shoemaker made history by cuddling up with asteroid Eros just two days before Valentine’s Day. And that unexpectedly successful date kicked off a continuing quest to unlock the secrets of these tiny worlds, as well as the clues they might hold about how we came to be.