Key Takeaways:

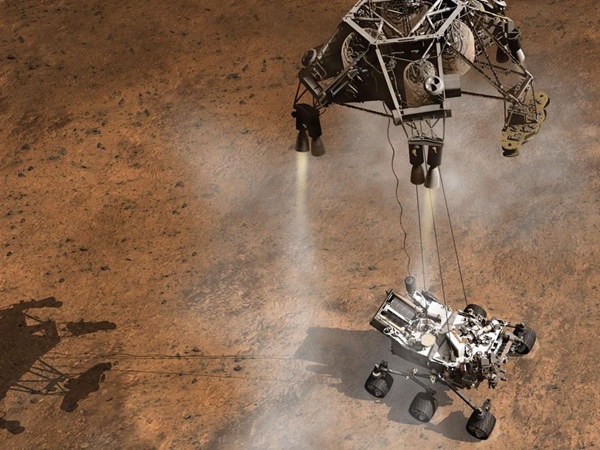

When NASA’s Perseverance rover lands on Mars this afternoon, the robot will owe its safe passage to one of the most unlikely pieces of technology developed since the dawn of the Space Age: the Skycrane. This seemingly sci-fi system sees the rover perilously dangle beneath a hovering rocket-powered spacecraft before being gently lowered to the ground (think Tom Cruise dropping from the ceiling in Mission Impossible).

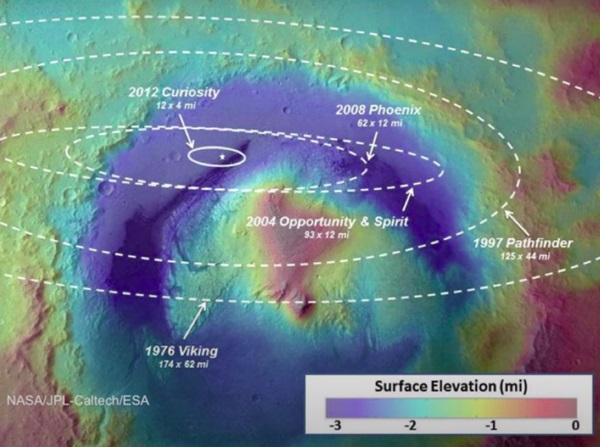

Though once considered an unrealistic solution to the problem of landing large craft on other worlds, today, engineers are confident the strange tech works. NASA has already successfully deployed it once. In 2012, the Skycrane safely set down the Mars Curiosity rover on the Red Planet. But when engineers first cooked up the idea nearly 20 years ago, few were sold on it.

The Skycrane was the consequence of considering — and then ruling out — every other option engineers could think of to land heavy rovers. And while the math checked out, there was no way to truly test it on Earth. So, engineers were left trusting a multi-billion dollar rover to a system that looked so bizarre and complex even the NASA administrator in charge at the time called it crazy.

“We talked about it to no end. If this didn’t go right, there would be nowhere to hide because every joe six-pack on the street would be saying that they knew it wouldn’t work,” Adam Steltzner of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, chief engineer for the Perseverance rover, tells Astronomy. His team dreamed up the Skycrane maneuver, and he was responsible for making sure it worked with Curiosity.

And while the system performed flawlessly in 2012, Steltzner and his team are not taking anything for granted this time around.

‘Seven minutes of terror’

When the Perseverance rover hits the Red Planet’s atmosphere today, it will be traveling at more than 10,000 miles per hour (16,000 kilometers per hour). That’s so fast that the rover would vaporize like a meteor if it weren’t safely tucked inside a heat-resistant, carbon fiber capsule that can withstanding temperatures up to a whopping 1,600 degrees Fahrenheit (870 degree Celsius).

These extreme temps are only the first challenge Perseverance will face during its death-defying plunge. Next, it needs to deploy its enormous supersonic parachute. Yet Perseverance’s parachute can only slow the craft to about 200 mph (320 km/h). And if it landed at that speed, the rover would create a nearly $3-billion crater.

Mars’ atmosphere is dense enough to pose major problems for engineers, but it’s still too thin for parachutes to fully slow down a plummeting lander. That’s why you need an additional step of the landing sequence that helps soften the rover’s touchdown. Steltzner likes to joke that it’s not the fall that kills you, it’s the landing.

Making matters worse, Mars is so far away from Earth that NASA can’t communicate with the spacecraft in real-time. Perseverance has to guide itself. By the time the spacecraft engineers back on Earth learn what’s happened, the rover will already have been dead or alive on Mars for seven minutes. NASA calls it the “seven minutes of terror.”

Mars rovers: From airbags to skycranes

And that’s why engineers have repeatedly come up with ingenious tactics for touching down on Mars. No one, or even two, solutions can accomplish the job.

The Viking landers used both parachutes and descent rockets to slow the spacecraft down just before landing, then the lander’s legs served as shock absorbers. Plus, Viking’s mission planners had to design special “showerhead” style rockets to avoid cooking the dirt beneath the spacecraft, which would have killed any potential signs of life they were looking for.

But when NASA started sending rovers to Mars, it quickly realized Viking’s tactics wouldn’t work. If the retro rockets fired too close to Mars’ dusty surface, they could fling rocks and debris back onto a delicate rover’s instruments and solar panels, putting it in danger.

That’s why NASA wrapped the Mars Exploration Rovers — Spirit and Opportunity — in airbags. Those airbags let the rovers safely bounce along Mars’ surface until they shed their final bit of momentum. Like the Skycrane maneuver, this bold idea was sound in theory, but seemed crazy at the time.

And in the years before the Mars Exploration Rovers were set to arrive at the Red Planet, the world’s space agencies got a series of painful reminders on the perils of interplanetary space travel. (Read more: The ‘Mars Underground’: How a Rag-Tag Group of Students Helped Spark a Return to the Red Planet.) Russia, Japan, The European Space Agency and the United Kingdom all saw missions fail at Mars. And NASA itself suffered back-to-back high-profile failures at Mars to round out the 1990s: the Mars Climate Orbiter burned up on entry and the Mars Polar Lander was destroyed during its landing.

At the turn of the millennium, NASA was keen on getting a win. And in 2003, its engineers delivered two successful landings — the Spirit and Opportunity rovers — using the audacious airbag system.

“We stuck two landings on the Mars Exploration Rovers, and when we got done with that we were pretty arrogant kids,” Steltzner recalls. With those successes in the bag, Steltzner and the other NASA engineers working on entry, descent and landing were riding high.

And as they looked ahead to what would eventually become the Mars Curiosity rover — a rover the size of a small car — they had to rethink the best ways to land on Mars. Their math showed airbags wouldn’t work; the rover was too beefy. There’s no known materials strong enough to handle Curiosity’s weight if they employed airbags like the ones used on Spirit and Opportunity. The tech simply couldn’t scale.

An alternative tactic would be to land the rover inside a platform, then have it drive off, as the tiny Sojourner rover did in 1996. But that approach also nearly killed Sojourner. And, as NASA learned with the Mars Polar Lander, depending on legs brings its own problems. The ill-fated Polar Lander likely died because the spacecraft misinterpreted vibrations in its legs.

So, way back in the early 2000s, NASA’s engineers decided to brainstorm and put together a list of every single idea they could come up with for landing a hefty rover on Mars. They went through them one at a time, ruling each one out for one reason or another. And that’s how Curiosity ended up with the Skycrane — nothing else seemed as likely to succeed. It proved to be the least crazy idea.

Curiosity Skycrane: “The Right Kind of Crazy”

The Skycrane works much like a heavy-lift helicopter (without the blades), using tether cables to lower the rover down to the surface while the crane relies on rocket propulsion to hover above. In fact, the team even consulted with the engineers and pilots behind the Sikorsky Skycrane, a helicopter that uses very similar technique to haul logs from forests, as well as other heavy cargo. But unlike earthly helicopters, as soon as the rover’s wheels hit Mars regolith, the flying crane shoots itself clear of the landing area, completing its task in a fiery explosion.

Unfortunately, there was no way on Earth to test how the rocket-powered Skycrane would perform on Mars. Engineers could run simulations and verify their calculations time and again. But they could never know for sure if Curiosity would actually survive the daring maneuver. And that’s what made it such a hard sell, even inside NASA.

At one point, the agency’s then-administrator, Mike Griffin, invited Steltzner to NASA headquarters to give a talk to managers from space centers around the country. As Steltzner stood at the lectern, Griffin walked in late wearing a turtleneck and double-breasted suit, then turned and addressed the audience. “When I heard what these guys are doing, I said to myself, these guys are crazy,” Griffen said, according to Steltzner. “So, I asked them to come here and explain what they’re doing.”

After Steltzner wrapped up his talk, the administrator and the engineer spent some time arguing back and forth before Griffin offered up: “I still think it’s crazy, but it might be crazy enough to work. It might be the right kind of crazy.”

The Skycrane becomes NASA’s norm

According to Steltzner, the overall skepticism surrounding the Skycrane notably changed after his talk at NASA headquarters. Previously, other engineers and space centers were hesitant to seriously support the wild idea. But with the administrator’s comments, that reluctance faded away. And as planning for the Curiosity mission pushed forward, NASA threw its full support behind the effort, Skycrane included.

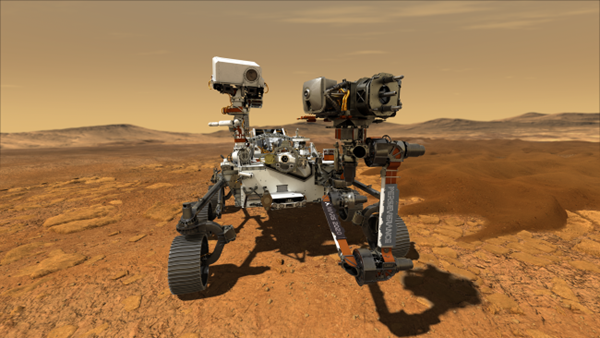

“If you’re landing a rover on Mars, there’s no doubt this is the right way,” Steltzner says.

The rovers are built to handle rough terrain. So, when the Skycrane drops it off at speed, it’s not significantly different than stumbling off a large rock. In fact, both Curiosity and Perseverance are tough enough that they could survive even if the Skycrane dropped them right on top of a small boulder. The Skycrane let NASA’s robotics engineers design a rover that could navigate the surface without worrying about having to make compromises just for its landing.

The technique has also proven to pair nicely with radar sensors that let the spacecraft observe its surroundings and autonomously guide itself to a safe area. This allowed the Curiosity rover to hit a relatively tiny landing target on Mars, and Perseverance will use a similar — yet even more precise — approach.

But according to Steltzner, that doesn’t mean the seven minutes of terror will be any less terrifying this time around.

“Last time, we certainly had questions about whether this really was a crazy thing to try to do,” he says. “Had we missed a big thing? Was it totally wrong? Did all the pieces actually come together and work? We answered those questions, but there are still hundreds of thousands of details you have to get right to make them work again. Our job is to make it work this time. I will be frightened all the way.”