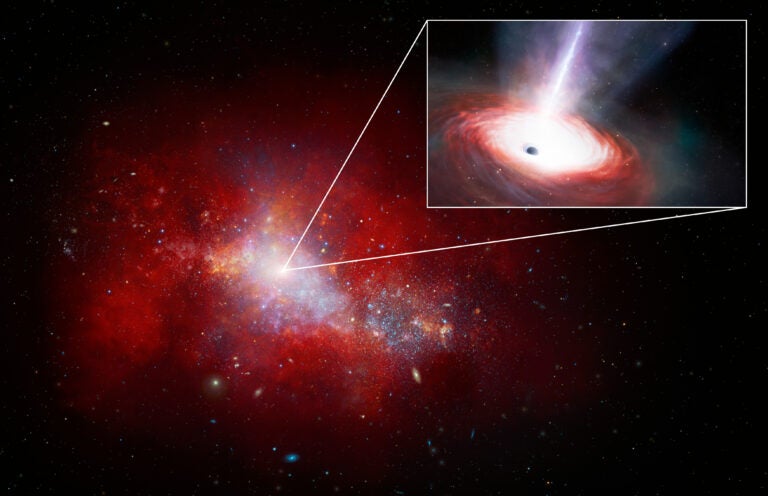

Black holes are a tricky bunch. While Einstein’s theory of relativity predicts they’re common, tracking down the first one was quite a challenge. Unlike stars, black holes themselves don’t emit any light, so the only thing we can measure about them is their size and spin.

Today, we know black holes exist — we even have a picture of one! But scientists haven’t had definitive evidence of black holes for very long. The first one, Cygnus X-1, was discovered in 1964. But it still took nearly 30 years for the two leading black hole physicists, Stephen Hawking and Kip Thorne, to agree Cygnus X-1 was really a black hole.

The famous black hole bet

There was little doubt in Hawking’s mind that black holes existed. After all, they were one of the focuses of his career. But whether scientists could actually find one was another question entirely.

That lack of discovery, understandably, made Hawking a bit nervous — which is why he hedged his research efforts with the bet.

“This was a form of insurance policy for me. I have done a lot of work on black holes, and it would all be wasted if it turned out that black holes do not exist,” said Hawking in his book, A Brief History of Time. “But in that case, I would have the consolation of winning my bet…”

He goes on to say that when the bet was first placed in 1975, he and Thorne were 80 percent certain that Cygnus X-1 was a black hole. By 1988, Hawking reported they were both 95 percent certain. Yet, they agreed, the bet could only be settled when they were both 100 percent sure.

By 1990, further observation had been done of the system, building enough evidence that it contained a black hole that Hawking was forced to concede the bet. And, according to Thorne, Hawking waited for the opportune moment to admit defeat.

“I was in Moscow … when Stephen and his entourage, with help from my students, broke into my Caltech office and he thumbprinted his concession,” Thorne told Astronomy via email. “When I returned [a] few weeks later, I saw it and celebrated — as did he. It was wonderful that the observations had become so firm that we were both fully convinced Cygnus X-1 is a black hole and a massive star orbiting each other.”

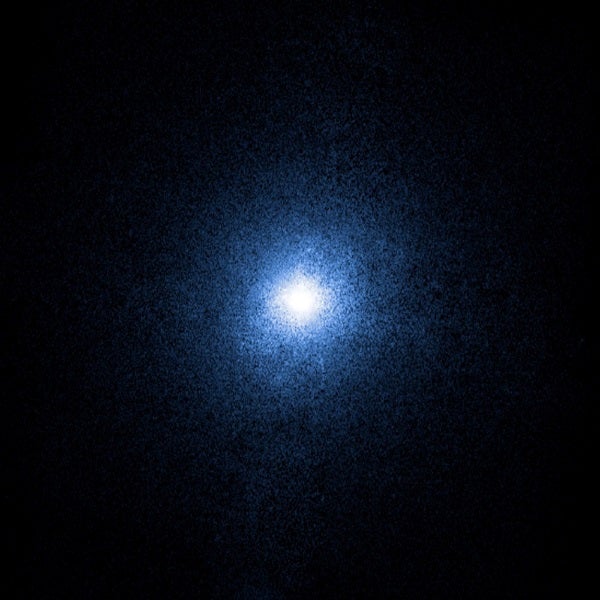

A closer look at Cygnus X-1

Cygnus X-1 was first discovered when a pair of Geiger counters were blasted high into the atmosphere aboard a sub-orbital rocket. The Geiger counters picked up a signal that scientists were able to trace back to a system containing a blue supergiant star orbiting another massive object some 7,200 light-years away. The second object, they determined, was also strongly radiating X-rays, which would make sense if it were a black hole.

Since its discovery in 1964, Cygnus X-1 has been the focus of numerous studies. But, as it turns out, the world’s first black hole isn’t done surprising physicists just yet.

A recent study, published Feb. 18 in Science, revealed the black hole is actually 21 solar masses. This makes the object the largest stellar-mass black hole ever discovered without the use of gravitational waves. And according to the researchers, this new measurement challenges astronomers’ understanding of how black holes form.

“Stars lose mass to their surrounding environment through stellar winds that blow away from their surface,” said co-author Ilya Mandel from Monash University in a press release. “But to make a black hole this heavy, we need to dial down the amount of mass that bright stars lose during their lifetimes.”

And Cygnus X-1’s exceptional mass isn’t its only record-breaking aspect. As co-author Xueshan Zhan explains, “Cygnus X-1 is spinning incredibly quickly — very close to the speed of light and faster than any other black hole found to date.” Such a high spin also deviates from the understood norm of black hole evolution.

Conclusive proof of black holes may be relatively recent, but it’s becoming increasingly clear they are peppered throughout the cosmos. So, even if astronomers eventually untangle all the mysteries of Cygnus X-1 — the first of its kind — its countless kin are sure to still hold many surprises.