Key Takeaways:

• The search for alien intelligence is one of the most compelling and important endeavors in modern science, but…

• …the interstellar object known as ‘Oumuamua is not the long-sought evidence demonstrating the existence of intelligent life elsewhere in the universe.

• And FYI, you don’t have to feel shy about not knowing how to pronounce ‘Oumuamua. Just say, “oh MOO uh MOO uh,” as if you were greeting two cows.

In case you’re not familiar with the story of ‘Oumuamua, here’s a quick recap. In October of 2017, a postdoc researcher named Robert Weryk, working with the Pan-STARRS telescope in Hawaii, detected a peculiar object moving away from the Sun at high speed. Its extreme, hyperbolic orbit indicated that the object was not a member of our solar system. It must have originated from far beyond, somewhere in interstellar space.

Astronomers had inferred that bits of debris from other star systems must transit close to us all the time, but this was first time one of them had ever been observed. The Pan-STARRS team named the object ‘Oumuamua, a Hawaiian word meaning, roughly, “advance messenger from afar.”

‘Oumuamua’s orbit was not the only surprising detail about it. As observers monitored the object, they measured it getting strongly brighter and dimmer, its brightness varying by about a factor of 10. The implication was that ‘Oumuamua has a highly asymmetrical shape, perhaps like a cigar tumbling in space: When we saw the long dimension it appeared bright, when we saw it roughly tip-on it appeared dim. Small celestial bodies often have ragged shapes, but such a strongly elongated form is, well, highly irregular.

Very puzzling!

To place these strange details in context, you should know that the amount of information we were able to gather about ‘Oumuamua was minuscule. It is a tiny object, already extremely faint when it was discovered, observed for just a few weeks. We still don’t know its true shape or its exact composition. We don’t know if it was shedding gases that we simply could not observe. But it was and is undeniably weird — weird enough that Avi Loeb at Harvard wondered if it might be an alien artifact rather than a natural interstellar interloper.

Since 2018, astronomers have lost sight of ‘Oumuamua completely. There’s no more information coming in. There is, however, a new book by Avi Loeb and a flurry of associated media coverage that has rekindled the debate over whether ‘Oumuamua might be evidence of alien technology — and that has sparked a whole new debate about the best way to investigate a claim like that.

From the start, many astronomers criticized Loeb for raising the possibility that ‘Oumuamua could be an alien artifact; several of them regarded his position as one based more on clickbait than on science. Loeb responded by saying that he believed all hypotheses should be open to investigation, and that there was no reason to exclude the possibility of extraterrestrial technology when considering the oddities of ‘Oumuamua. I had a long conversation with him and I largely agreed with him about the value of airing unconventional ideas.

Since then, Loeb has also made outspoken comments that SETI (the search for extraterrestrial intelligence) deserves more attention and more funding. His tone was wildly inappropriate at times, but I agreed with his overall argument here, too. The detection of an alien civilization would revolutionize science, and probably culture, politics, religion, and ethics as well. It’s ridiculous that NASA was effectively blocked from funding any SETI projects after 1992, and only began doing so again last year.

Where Loeb lost me is when he shifted from championing open-mindedness to championing his specific hypothesis about ‘Oumuamua. Of course it is essential to keep looking for unexpected and inexplicable phenomena, and of course we should scrutinize anything that could be a sign of alien intelligence. But that’s a long way from stating, as Loeb does in the introduction to his book Extraterrestrial, that “the simplest explanation for these peculiarities [of ‘Oumuamua] is that the object was created by an intelligent civilization not of this Earth.”

The possibility of extraterrestrial intelligence is so captivating and staggering that it tends to inspire irrational, knee-jerk responses. Normally sober publications like The New York Times published oddly naive essays about the ‘Oumuamua controversy. People with no particular expertise in astrobiology often have strong opinions on the topic of alien civilizations — that they must exist in such a vast universe, for instance, or that the whole topic is ridiculous and unscientific. I find it hard to check my own emotions on the topic, and Avi Loeb appears to have fallen into the trap as well.

An effective tool for returning to sanity is the famous Drake equation. It’s not a equation so much as a succinct summary of all the huge, glorious unknowns in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. In his book, Loeb calls the Drake equation “nothing more than a heuristic, a shorthand tool.” His description is not inaccurate, but his dismissive attitude is. The Drake equation is a way to make sure we are asking the right questions, and not substituting intuition for actual answers.

Each term in the Drake equation sets the conditional probability of the term that comes after. In probability statistics, this concept is known as a Bayesian prior. It is fundamentally nothing more than a piece of information that influences your beliefs about the likelihood of another event.

To give a blunt analogy: Suppose your friend told you that a leprechaun broke into your car and stole it. You’d find that rather hard to believe, and demand some extremely convincing proof. Now suppose that we lived in a world in which we knew that leprechauns were real and that they were commonplace. That additional piece of prior information would make you vastly more likely to believe your friend’s story.

In more subtle (and less ridiculous) ways, the same is true of the terms of the Drake equation. Do most stars have habitable planets? If so, that influences your thinking about the likelihood that some of those planets actually produce life. Is life common throughout the universe? If so, that influences your thinking about the likelihood that some of those planets host sentient beings that could produce space-faring technology.

This concept is the foundation of the familiar dictum, popularized by Carl Sagan, that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” In Extraterrestrial, Avi Loeb writes that “it is not obvious to me why extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence (evidence is evidence, no?).” Prior information is the reason why.

If we already knew that space was full of alien spaceships, the standard of evidence for identifying ‘Oumuamua as one of them would be very low. Given that we don’t know whether life exists anywhere in the universe beyond Earth, the standard is very high. The grand ambition of astrobiology in general, and SETI in particular, is to glean more information about the various aspects of life in the universe, filling in details about each of the factors in the Drake equation.

That said, there is no reason why we need to work through the Drake equation factor by factor, left to right. Every part of it could and should be investigated right now; Loeb is entirely correct on this point. Right now, we know only the first two factors with any degree of confidence. Anything we learn about one of the subsequent factors will inform our understanding of all the others. Every discovery will get us one step closer to answering the existential question of astronomy, and of life in general: Are we alone?

Note, too, that every factor in the Drake equation is a huge mystery in itself. We don’t need to invoke alien spaceships to make this research captivating and personal. We still have so much to learn about life and the universe and our place in the great order of existence.

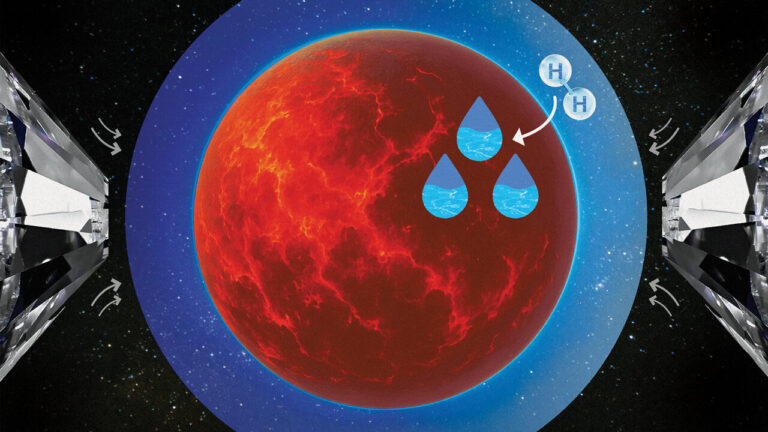

Consider the 3rd factor, the number of habitable worlds that exist in an average planetary system, and the 4th, the fraction of habitable worlds on which life actually appears. We don’t even know what those numbers are in our own solar system! We might find life on Mars, Europa, and Enceladus and realize that living worlds are extremely common. Or we might find nothing but barren land, and no signs of life on superficially earthlike planets around other stars. Earth might be part of a vast web of cosmic biology, or it might be a rare — even unique — outlier. Either answer would transform the way we view ourselves.

I’m especially fascinated by th 5th factor, the fraction of life-bearing worlds on which intelligence appears. People often whiggishly assume that the natural tendency of evolution is to produce our style of intelligence. But the basic elements for high-level cognition have existed among living things for well over 200 million years, yet Homo sapiens have been around only about 1/1000th that long. It’s not at all clear that self-aware intelligence is an inevitable evolutionary outcome.

To me, this is the great lesson from ‘Oumuamua, along with all the media hype and scientific gnashing it has inspired: We must keep looking for other intelligence out there in the universe, but we must do it with relentless self-awareness of our biases. Until we have a deeper understanding of where and how life arises, it’s meaningless to claim that an alien spaceship is the “simplest explanation” for the enigma of ‘Oumuamua.

A more honest position is that every astronomical enigma, every inexplicable discovery, is another potential clue. We should keep looking for them, not only because we might discover alien life, but also because we will learn something exciting no matter what.

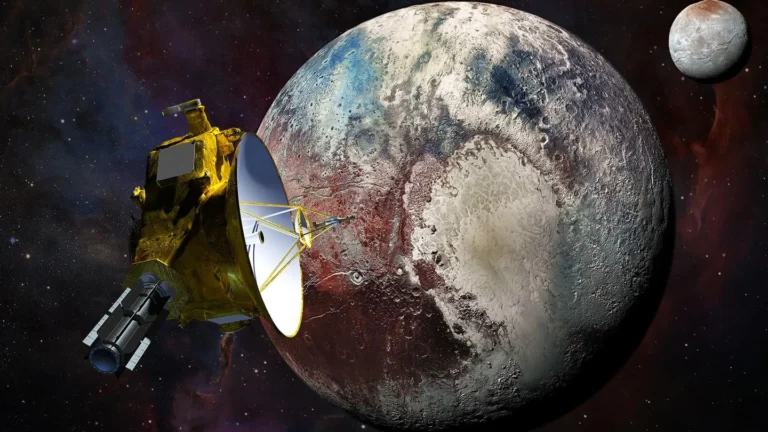

‘Oumuamua was soon followed by a second interstellar object, Comet Borisov, which looked much more like a conventional solar-system comet. The upcoming Rubin Observatory is likely to discover many more such objects, so soon we will know whether ‘Oumuamua is one of a whole population, or a true outlier. SETI researchers are moving beyond radio, looking for optical signals or chemical evidence of extraterrestrial civilizations, scanning for unusual natural phenomena along the way.

NASA and the National Science Foundation are tentatively restoring support for SETI. Private efforts like Breakthrough Initiatives are jolting the field with new funding and new ideas. The public is clearly captivated by these ideas, which makes it all the more frustrating that we as a society spend so little money investigating such a fundamental question.

‘Oumuamua, faint though it is, can be a beacon to us. It can show us a way to do better and search harder. Not because we think it is likely to be an alien spaceship but because, dammit, if there are alien ships out there — or alien whales or trees or microbes, for that matter — we want to know. We want to unleash the full power of the human intellect to seek out any other members of our cosmic family. But we need to do it with honesty, transparency, and humility.