Rainfall is one of the defining characteristics of our weather, with amounts varying dramatically from one region to another. It shapes both our skies and our landscape, carving valleys while filling rivers and lakes.

We know similar processes are also at work elsewhere. Titan, too, has rivers, lakes, valley networks and rain, even though the fluid involved is quite different — liquid methane instead of water.

Mars also seems to bear the marks of rainfall, albeit from some billions of years ago. Although gas giants such as Jupiter and Saturn have no surface, raindrops are thought to play a crucial role in the dramatic storms visible on their surfaces because the drops transport heat through the atmosphere.

And that raises an interesting question: what of rain on even more distant; how similar is it likely to be to rain on Earth?

Now we get an answer, thanks to the work of Kaitlyn Loftus and Robin Wordsworth, both at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This pair says just three factors determine the size of raindrops in any given atmosphere, regardless of the way the drops form. Because of this, Loftus and Wordsworth say raindrops on other planets are likely to share remarkable similarities to raindrops here on Earth.

Cloud mechanics

First, some background. Raindrops form and grow inside clouds when water vapor condenses around much smaller particles such as aerosols. This turns out to be a complex non-linear process. Condensation redistributes heat and humidity within the cloud, which in turn affects future drop formation. Exactly how this happens over the vast range of spatial scales inside clouds is poorly understood.

Nevertheless, the drops that form in this process are remarkably similar. Most raindrops are about a millimeter in scale and almost none are bigger than 4mm across because any larger drops break apart. The size is uniform because the physics that governs the drops as they pass through the atmosphere is the same for them all, regardless of how they form.

Loftus and Wordsworth say that just three properties play a role — the shape of the raindrop, its terminal velocity and its rate of evaporation as it falls. “From these properties, we demonstrate that, across a wide range of planetary conditions, only raindrops in a relatively narrow size range can reach the surface from clouds,” say the researchers.

The shape of raindrops is relatively well understood. “Falling raindrops adopt a range of shapes depending on their size — though never the teardrop shape inscribed in the public imagination,” says Loftus and Wordsworth. “As raindrops grow in mass, they evolve from spheres to oblate spheroids to shapes resembling the top of a hamburger bun.”

The researchers can also determine the terminal velocity of raindrops in any atmosphere. This depends on the forces acting downwards — gravity — and the aerodynamic drag which acts in the opposite direction.

This in turn depends on factors such as the cross-section of the raindrop, its speed through the atmosphere, the density and viscosity of the atmosphere, and so on. When these forces balance, the drop falls at a steady, or terminal, speed.

On Earth this happens very quickly. Loftus and Wordsworth say even the largest raindrops accelerate to 99 percent of their terminal velocity within 1 percent of their total fall distance.

They also study how changes in drop size, caused by evaporation, for example, influence this speed. Not by much, it turns out. So it’s likely that drops in other atmospheres will behave in the same way.

Finally, the pair look at the evaporation rate of raindrops. This is a little more complex because the evaporation rate at the drop’s surface depends on the surrounding humidity, the density of the atmosphere, how vapor diffuses through it and of course the temperature of the drop and surrounding air.

The movement through the air can change this temperature as does heat transport via conduction and at higher temperatures by radiation. So the physics is complex. Nevertheless, the researchers say that with all things considered, the evaporation rate can be characterized by a single parameter.

Surface tension

They go on to calculate the size that raindrops can grow to in a wide range of conditions. One important factor is that raindrops are held together by the surface tension of the liquid. But when external forces become stronger than this, the drops break apart. This process prevents raindrops on Earth ever growing bigger than a few millimeters across.

Loftus and Wordsworth say that a similar limit will exist in other atmospheres over a wide range of conditions. So in general, extraterrestrial raindrops will be a similar size to those on Earth within a few factors, but not by orders of magnitude.

“For terrestrial planets, raindrops sizes capable of transporting condensed mass to the surface only span about an order of magnitude,” they say. “We show across a wide range of condensables and planetary parameters that maximum raindrop sizes do not significantly vary.”

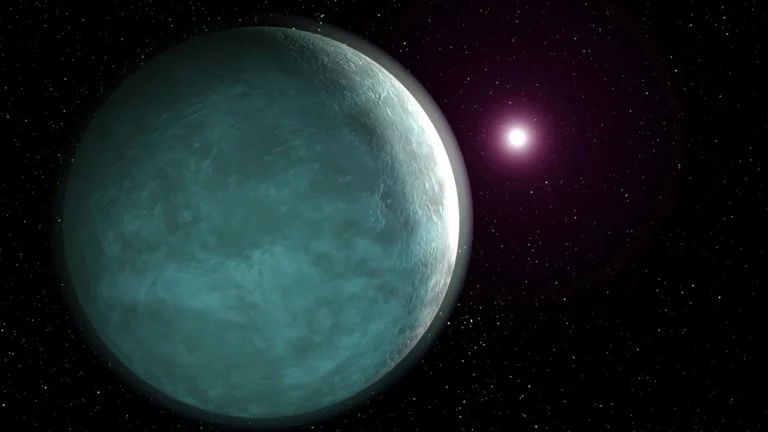

The team points out that the same physics applies to drops that are not composed of water. Astronomers have observed iron condensing in the ultra-hot atmosphere of an exoplanet called WASP-76b. The “iron rain” here should follow the same rules. Indeed, similar temperatures, and presumably similar phenomenon, can occur on Earth during meteor impacts.

That’s a fascinating step towards a general description of raindrop behavior on other planets. Perhaps Loftus and Wordsworth will devote their next paper to extraterrestrial rainbows.

Ref: The Physics of Falling Raindrops in Diverse Planetary Atmospheres: arxiv.org/abs/2102.09570