Once upon a time, GJ 1132 b was a smallish gas giant planet. Then powerful radiation from its parent star burned off its massive envelope of gas, leaving behind only a desiccated rocky core — a super-Earth, about 1.6 times the mass of our planet.

Now, a group led by researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena has analyzed Hubble Space Telescope observations of GJ 1132 b and found something very peculiar: the planet seems to have reestablished an atmosphere. Furthermore, the composition of the gases suggests a volcanic origin.

Based on what we know of our own solar system, full atmospheric makeovers on rocky planets are not uncommon. Earth’s atmosphere has been completely remade twice — first by volcanic activity and meteorite impacts, and then by the emergence of life. Mars is on its second or third atmosphere. But this is the first time that a secondary atmosphere has been reported on an exoplanet.

Some researchers think the detection is more tentative than the team claims. But if it stands, it could have wider implications for theories of planetary formation — and demonstrate that studying exoplanet atmospheres can also offer insight into what happens below the surface.

Refreshed air

GJ 1132 b orbits a red dwarf only 40 light years from Earth in the constellation Vela. It was discovered in 2015 by a Harvard-led team using an array of small ground-based telescopes to look for transits — when a planet crosses in front of its host star and dims it slightly.

During transits, astronomers can also study an exoplanet’s atmosphere by observing what wavelengths the atmosphere absorbs as light from its host star passes through it. Using this method, in 2017, a European team reported finding a water-rich atmosphere. However, follow-up observations by some of the planet’s discoverers called this into question; the team argued their data were consistent with no atmosphere at all. A lack of atmosphere also aligned with theory, which predicts that a rocky world so close to its host star cannot retain its primordial atmosphere — it would quickly evaporate into space.

But the new study, accepted for publication in the Astronomical Journal and posted March 10 to the arXiv preprint server, adds weight yet again to the idea that GJ 1132 b has an atmosphere. Using data that Hubble collected in 2016, the researchers identified gases including hydrogen cyanide and methane. “This world really stood out because it is small, and with a clear spectral signature,” says JPL’s Mark Swain, who led the work.

However, this does not completely overturn theory. The team modelled the evolution of the planet and concluded that GJ 1132 b — whose temperature is a sweltering 440 degrees Fahrenheit (227 degrees Celsius) — likely did lose its original atmosphere of hydrogen and helium in the first 100 million years of its evolution. This means that what they detected is the planet’s second atmosphere.

“It is very likely that the planet lost everything at the very beginning,” says JPL’s Raissa Estrela, a study co-author. “But the transit observations show spectral features which means there definitely is an atmosphere.” And those features, she adds, suggest that the gases are rich in hydrogen and low in oxygen content — which suggests they might be explained by volcanic outgassing.

Volcanic origins

Detecting a secondary atmosphere derived from volcanic activity would be a first for exoplanet studies.

Before GJ 1132 b, all the exoplanet atmospheres we’ve ever seen are thought to have formed the same way: during the initial formation of the local system, protoplanets grow by accreting material from the disk of gas around their host stars, and their atmospheres are derived from a leftover envelope of gas.

Since their modelling ruled out the possibility of this primordial atmosphere surviving on GJ 1132 b, Swain and his colleagues turned to a 2019 paper that proposes a stage in the process where a nascent planet accreting a hydrogen atmosphere can absorb that hydrogen into its molten mantle. This reservoir of hydrogen, the team proposes, could be released later through volcanic activity.

There is some evidence for this cycle happening on the primordial Earth, the team says, which had a very different air composition than it does today. “There are some rocks that have been dug up from the Earth’s mantle that show a very low oxygen content,” says Swain. Many geologists think that these rocks formed when Earth had a primordial, hydrogen-rich atmosphere — which eventually went deep into the ground.

The team modelled this possibility for GJ 1132 b and found that if this hydrogen-rich magma released its gas above ground, it could produce what they observed in the atmosphere. This includes features like the planet’s unusually high levels of hydrogen cyanide, which makes up about 0.5 percent of the planet’s total atmosphere.

The study is the first to connect atmospheric observations to formation theories of a planet’s mantle, which also has wider implications for studying exoplanet formation. One line of thought holds that many super-Earths are actually the leftover cores of sub-Neptunes — a class of gaseous planet whose growth stalls out before it can reach Neptune size — that have lost their primordial envelope of gas. This study raises the possibility that these worlds may still host atmospheres that astronomers can study, even when those planets are very close to their host stars.

“What our results provide is observational evidence that, at least in some cases, this class of planet can reestablish an atmosphere,” says Swain.

A promising follow-up target

Leslie Rogers, an astrophysicist at the University of Chicago who was not involved in this study, doesn’t think the evidence for a secondary atmosphere is definitive. “I think they could have better quantified the statistical significance of their results,” she says.

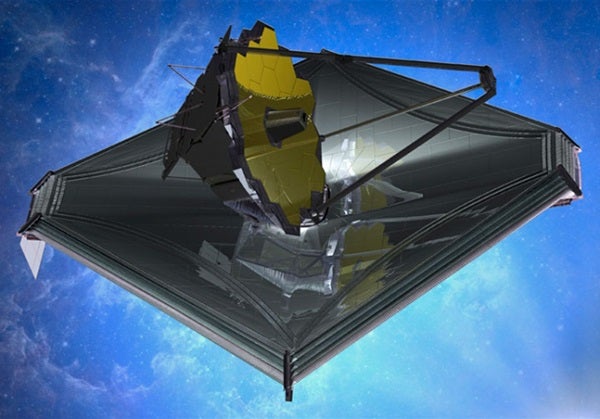

But she concedes that for any rocky planet, getting atmospheric observations with good signal-to-noise ratio is a challenge. This is why astronomers are looking forward to the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which is slated to launch October 31, 2021. It will have far better precision and observational sensitivity for characterizing the atmospheres of exoplanets than current instruments.

Rogers thinks that although the new study is not conclusive, “the observation hints at an unusual world which is certainly worth another look.” The competition for time on JWST will be fierce, she adds, “but these new Hubble results could give a boost to a proposal.”