The person who probably did the most to bring various efforts to the attention of the public was astronomer Carl Sagan. But the notion of, and belief in, alien life was around long before radio telescopes or science popularizers. So where did the idea that we’re not alone in the universe get started? Since when did earthlings look up at the sky and think, hey, is anybody else home?

Atomic theory, round one

In his book Life on Other Worlds, astronomer and science historian Steven J. Dick explains that the notion of life elsewhere in the cosmos came up at least as long ago as the ancient Greeks. Atomism was a view developed by the Greek scholar Democritus in the fifth century BCE, and argued that everything in existence is made up of tiny particles that are both infinite in number and unchangeable. All the things we see around us are simply different arrangements of these invisible particles. The theory that everything in the universe is made of the same basic stuff led quite naturally to the idea that if there is life on Earth, there could well be life elsewhere.

Epicurus (341-270 BCE), the founder of the school of philosophy known as Epicureanism, later revived and refined atomism. The implications regarding life on other planets were not lost on him. In a letter to Herodotus, Epicurus made an argument that will seem familiar today:

“There is an infinite number of worlds, some like this world, others unlike it. … For the atoms out of which a world might arise, or by which a world might be formed, have not all been expended on one world or a finite number of worlds, whether like or unlike this one. Hence there will be nothing to hinder an infinity of worlds.”

So in an infinity of worlds, you may well have another — perhaps several other — worlds very much like our own. Or as some might say today, in an infinite universe, anything that can happen does happen.

Epicurus also pointed out that:

“… nobody could prove one way or the other that in one sort of world there would be found the beginnings out of which animals, plants and all the rest of the things we see arise, and that in another sort of world this would have been impossible.”

The Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius (circa 99-55 BCE) helped spread and explain Epicurean ideas in his book De Rerum Natura, or in English, On the Nature of Things.

Modern thinkers take over the search

The idea gained even more traction after the Copernican Revolution. When scholars began to accept that the Earth was not the center of the solar system, but one of a number of planets orbiting the sun, it was not hard to imagine those other planets were inhabited, too. Thinkers such as Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler certainly considered the possibility, though they had a problem that Epicurus and Lucretius did not: The Catholic Church. The Church did not officially accept the Copernican world view until 1822. Of course that did not keep people from looking at the skies and speculating about who might live there; they just did it more circumspectly than the ancient Greeks had.

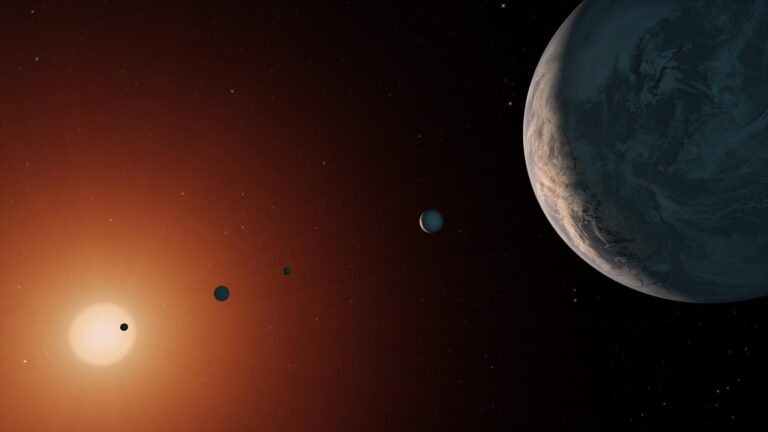

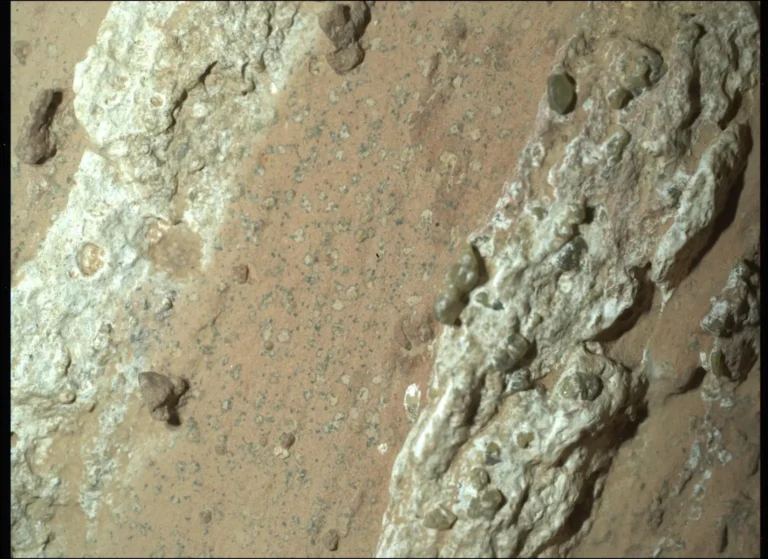

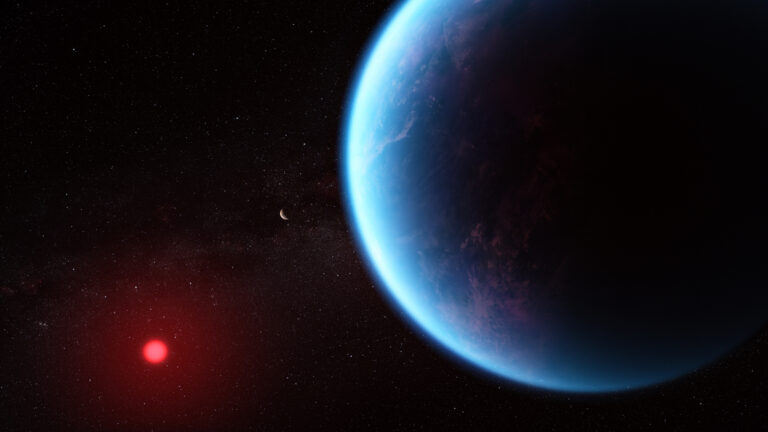

Today, we not only speculate about alien life, we go in search of it. The mission of the Mars rover Perseverance is to seek signs of ancient life on the red planet. If Perseverance does find signs of life, it would likely be microbial life. Though the ancient Greeks could easily imagine plants and animals on other worlds, they had little understanding of microscopic life living on their own planet and in their own bodies. Still it’s easy to imagine them being delighted by the notion, and not at all surprised that their descendants are seeking it on Mars.