Key Takeaways:

- William Herschel, a self-taught astronomer and musician, discovered Uranus on March 13, 1781, initially believing it to be a comet due to its initially perceived size and lack of a tail.

- Subsequent observations by Herschel and other astronomers, including Nevil Maskelyne, Anders Lexell, Jean-Baptiste Saron, and Pierre Laplace, confirmed Uranus' planetary nature and significantly expanded the known size of the solar system.

- While Herschel initially proposed naming the planet "Georgium Sidus" in honor of King George III, the name Uranus, proposed by Johann Elert Bode, ultimately prevailed, aligning with classical mythological naming conventions.

- Uranus had been observed previously by John Flamsteed and Pierre Charles Lemonnier, but its planetary status remained unrecognized until Herschel's discovery.

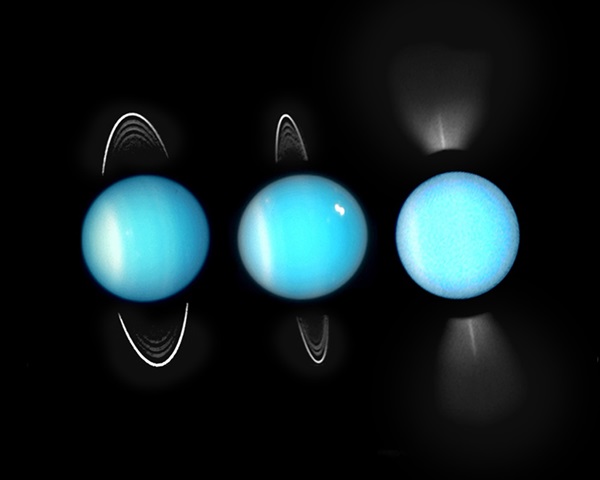

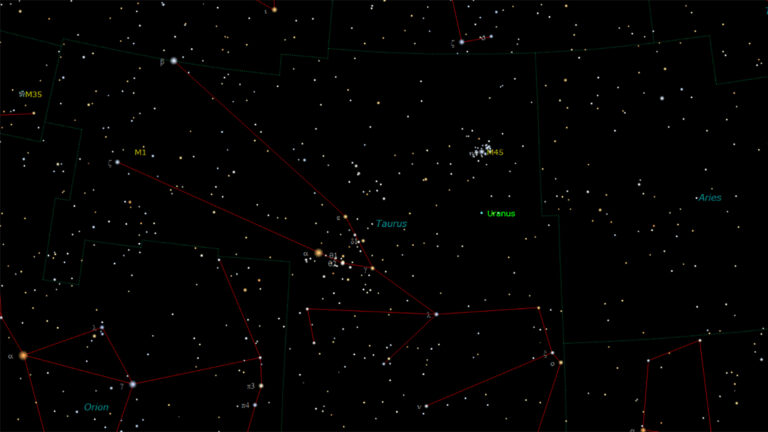

Step out to your backyard tonight and give your eyes a few minutes to acclimate to the darkness. Glancing eastward, just a handful of degrees above the horizon, you might discover a tiny gem shimmering at roughly sixth magnitude, hidden within the mid-sized constellation Aries the Ram. A telescope or binoculars should sharpen it into stark relief, revealing an unmistakably aquamarine hue.

If luck is on your side, you’ve just found Uranus — a planet which, until 240 years ago, humanity did not know existed.

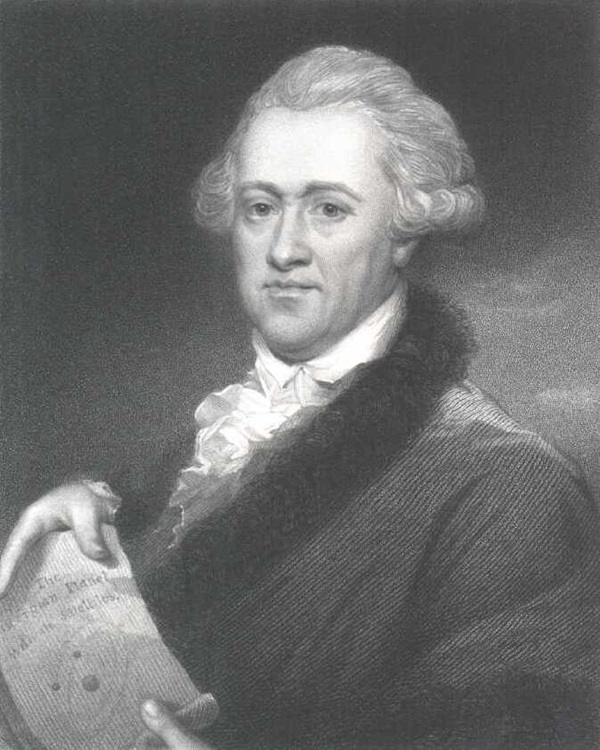

The man who discovered the ice giant, William Herschel (1738-1822), was a self-educated genius, the progeny of a German musical family whose Hanoverian father sent him to Britain after the Seven Years’ War with France. There, Herschel proved a quick study in the English language, and he established himself as an organist, violinist, oboist, and harpsichordist in the wealthy Somerset spa town of Bath.

Keen for upward social mobility and professional advancement, Herschel was well-read, teaching himself mathematics, trigonometry, mechanics, and optics. It was this innate curiosity which drew him, moth-like, to the entrancing flame of astronomy.

With his younger sister Caroline (1750-1848), the siblings ground and polished mirrors from a highly reflective metal (speculum, which is two-thirds copper and one-third tin), built their own telescopes, and used those scopes to target the sources of some of the thorniest mysteries of the 18th-century’s night sky.

Herschel stumbles onto something odd

From the garden of the Herschels’ five-story townhouse — which is now a museum — on New King Street in fashionable Bath, this intrepid brother-and-sister team observed a peculiar breed of celestial objects called double stars. By carefully measuring their proper motions, or the stars’ apparent movements compared to more distant stars, the Herschels hoped to discern clues about their distances.

But on the clear Tuesday evening of March 13, 1781, as 42-year-old William Herschel hunkered down at the eyepiece of his 6.2-inch Newtonian reflector, he saw something he did not expect.

Between 10 and 11 o’clock, “while I was examining the small stars in the neighbourhood of H Geminorum,” Herschel wrote, “[my attention was drawn to] one that appeared visibly larger than the rest.”

Struck by the difference in both magnitude and apparent size, Herschel first thought he had discovered a new comet. But four nights later, he spotted the object again, which thickened the plot. It seemed odd, Herschel mused, for any comet to possess such a well-defined disk — much less the complete absence of a long, gaseous tail in its wake.

He reported his find to the Royal Society, as well as his close friend, Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne. “In the quartile near Tauri,” we can imagine Herschel writing in his journal by the dim glow of a candle, “the lowest of two is a curious, either nebulous star or perhaps a comet.”

The solar system gets a new planet

It soon became obvious that the aquamarine object was no comet. And suspicions on the part of both Herschel and Maskelyne were made clear in their letters.

“I am to acknowledge my obligation to you for the communication of your discovery of the present comet, or planet, I don’t know which to call it,” Maskelyne wrote. “It is as likely to be a regular planet moving in an orbit nearly circular round the Sun as a comet moving in a very eccentric ellipsis.”

Over the next several months, Swedish astronomer Anders Lexell and French astronomers Jean-Baptiste Saron and Pierre Laplace worked to show that the object’s orbital characteristics were indeed more akin to a planet than a comet.

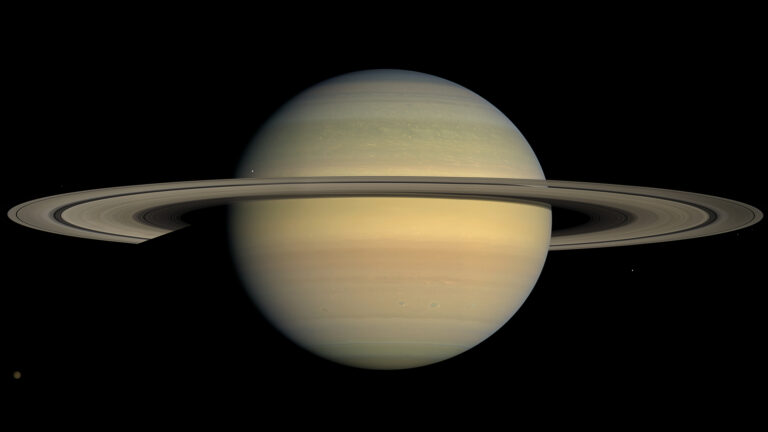

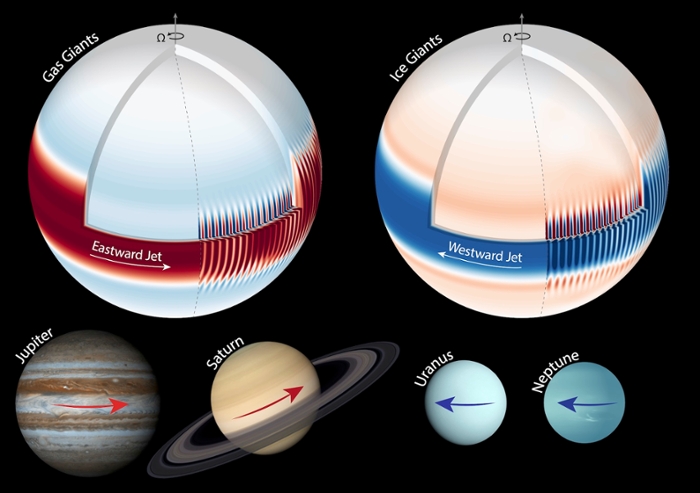

The significance of discovering yet-to-be-named Uranus was profound. For millennia, even the most educated people knew of only six planets — from tiny, Sun-hugging Mercury to ring-bedecked and distant Saturn. And calculations of Uranus’ orbit indicated that this seventh planet lay twice as far from the Sun as Saturn. In a single night, Herschel essentially doubled the size of the known solar system.

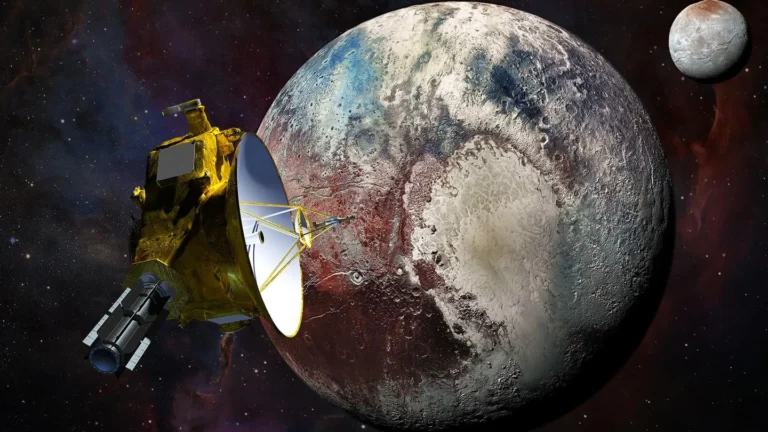

The new planet was not just distant, either. It was enormous. Herschel suggested an equatorial diameter of 34,000 miles (55,000 kilometers), roughly four times wider than Earth. This estimate turned out to be impressively close to the 32,000 miles (51,500 km) diameter derived from Voyager 2 spacecraft data.

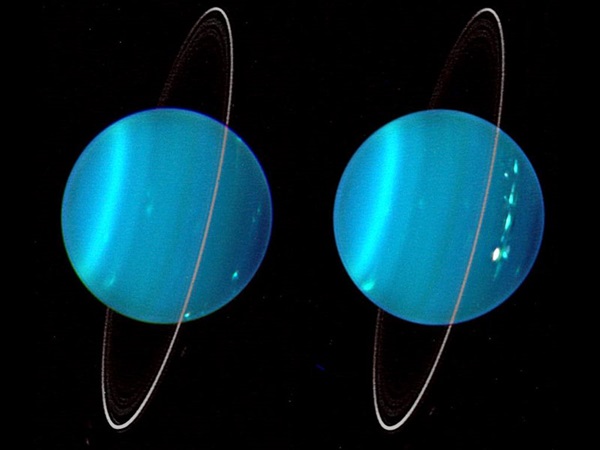

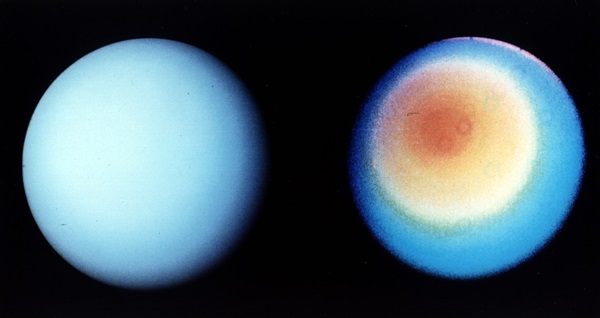

Voyager 2 captured these images of Uranus at a distance of 9.1 million miles (14.5 million km) in 1986. The left image used blue, green, and orange filters, and it was processed to approximate the true color of the planet. The view on the right was taken wit different filters and the contrast was exaggerated.

Intriguingly, though, Herschel was not the first person to spot Uranus. The faint world had been seen many times before. Yet, its true nature went unrecognised. Britain’s first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, observed Uranus six times in 1690, but catalogued it as a star. And French astronomer Pierre Charles Lemonnier spotted it a dozen times between 1750 and 1769, including sightings on four consecutive nights.

Finding a fitting name

For Herschel himself, as Uranus’ discoverer, the honors came thick and fast: membership to the Royal Society, receipt of the prestigious Copley Medal, a royal pension, and funding to build the biggest telescope in the world at that time.

Nonetheless, naming the new planet proved a tough nut to crack. Some astronomers felt it should be named for its discoverer. But Herschel, intent on currying favor with Britain’s King George III, suggested Georgium Sidus (“Georgian Star”).

In his writings, Herschel tried to rationalize this pompously cumbersome choice. “The first consideration of any particular event, or remarkable incident, seems to be its chronology,” he wrote. “If in any future age it should be asked, when this last-found planet was discovered, it would be a very satisfactory answer to say: In the reign of King George the Third.”

Unsurprisingly, in the final years of the 18th century, royal references were poorly received by the United States, as well as by Britain’s nemesis France, as well as other countries who were not fond of the crown. Astronomers also scoffed at the indication that the Georgian Star, in any shape or form, was a star. And to top it off, naming the world after a king was totally at odds with the classical naming tradition for planets.

The name Uranus comes from Greek mythology and was proposed in 1783 by German astronomer Johann Elert Bode. It was a nod to the Roman god Caelus, the mythological father of Saturn (Cronus), who fathered Jupiter (Zeus), who, in turn, fathered Mercury, Venus, and Mars. The name not only fit, but stuck.

By pure happenstance, when Herschel died in 1822, the span of his life had run the same number of years — 84 — that Uranus takes to circle the Sun once. On Herschel’s epitaph at St. Laurence’s Church in Berkshire, an inscription reads: “He broke through the barriers of the heavens.” And indeed, by doubling the known size of the solar system, the man who found Uranus did just that.