Key Takeaways:

When I was eight years old, a mundane school assignment changed my life. In my class at Lomond Elementary in Shaker Heights, Ohio, I had to write a school report about one of the planets. To ensure variety, the teacher picked a planet for each student. Mostly the kids wanted Saturn (the one with the cool rings) or Mars (the one where Martians come from). I got…Neptune.

Bummer. Who wants Neptune? What even is Neptune? I wanted Saturn or Mars, too! I dug out an old copy of the Golden Book of Astronomy that my parents bought for my older brother. I started reading about Neptune. And I was hooked.

Neptune is cold, dim, distant, slow, strange, enigmatic, exotic, alone. (Remember, this was many years before Voyager 2 flew past the planet, so it was really unknown back then.) To my young self — feeling like an oddball in a new school in a new city — Neptune seemed a kindred spirit. It circled out there, 30 times as far from the Sun as Earth, chilling in perpetual twilight, proudly mysterious and full of promise. Neptune didn’t need to be known, but it could be known if we really wanted to make the effort.

I was responding, no doubt, to the inescapable human tendency to project personal qualities on inanimate objects. But at a half-comprehending level, I was also realizing that astronomy, like all of science, is a gloriously personal process. The only reason that we knew anything at all about Neptune was because somebody wondered and did make that effort to find out. All of the things that we still didn’t know about the planet were waiting, up for grabs, for somebody else to come along and make a new, more effective effort.

At the time, I could not have articulated why I cared about the planets and stars. There was no immediate practical benefit to studying Neptune, and there was no immediate practical benefit to me from knowing about Neptune. But so what? The benefit to me was that knowing about Neptune, and all the other astronomical wonders it led me to, gave me a thrilling new perspective on my life. The universe felt bigger and richer to the part of me that connected to religious faith. It felt bigger and richer to the part that didn’t as well.

From my current adult perspective, it’s easy enough to come up with a list of pragmatic advances that justify investing in astronomy. If you regularly read popular science stories, you have probably encountered some of these arguments: Over the centuries, astronomical research and space exploration have driven critical advances in timekeeping, navigation, optics technology, digital imaging, and high-speed computing. But the nuts-and-bolts, dollars-and-cents payout is not the point.

Or rather, the tangible benefits are only part of the point. They are the side-effect, the colossal bonus that comes with an activated sense of curiosity. Curiosity and wonder inevitably lead to those benefits. The process does not work the other way. The tangible benefits do not necessarily trigger feelings of wonder. People can tap away endlessly on their iPhones, living disease-free and well-fed in their modern homes, and have no strong appreciation for how those things came to be.

To be clear, I don’t blame anyone for feeling this disconnect. Life is busy, and many scientific concepts are challenging or downright intimidating as commonly presented. On the contrary, I regret that so many people are alienated from the joyous discoveries all around them. I am always looking for ways to bring them back.

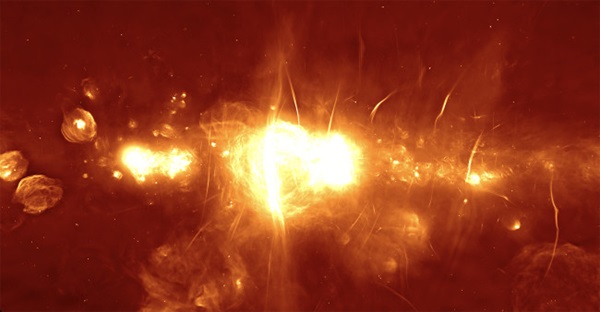

I think of astronomy as a wedge that helps open people’s minds, reawakening or amplifying that wonder instinct we were all born with. Staring off to the stars, we are looking back into time. With the naked eye, we can see the Andromeda galaxy, 2.5 million years in the past, around the time the first Homo species evolved. Through great telescopes we can easily see back to a time before Earth even existed. And everywhere we look, in every direction, we are gazing past far-off planetary systems where life, even intelligent life, might well be looking back.

Astronomy does not trigger the same kind of reflexive political and cultural responses as climate change (“are they going to raise my taxes?”) or public health (“I should be free to do what I want”). It gives people a wide-open space, literally, to think about what human minds can do when set loose to gather information, formulate ideas, test hypotheses, seek better answers. And then, maybe, they can turn back to the politicized issues and see that there, too, the path to the better answers is exactly the same.

The reason astronomy is an effective wedge is precisely because it is impractical and emotional. It shows the possibility of answers even to questions that seem impossibly difficult, the possibility of casting light into the darkness. It works as a wedge, too, because it shows how much of our experience of the world depends on equality and fairness. Wonder and curiosity are not fully available to people who are living in hunger, lacking health services, in economic desperation, or without access to education and to the other tools that help an inquisitive mind wander wherever it wants to go.

Wonder should be available to everyone.

We live in an age of great challenges, but the truth is, humans always have. As the technological capabilities of our species have expanded, so too has the scope of the dangers we face — many of them dangers of our own making. Global travel and shrinking wilderness areas foster the rise of pandemics like Covid-19. Human activity is changing Earth’s climate and driving species to extinction. We rely on fragile systems of electrical connections, software, and modern materials that we have built up more quickly than we can safeguard them.

And yet, I am resolutely optimistic that we can rise to these challenges as we have before. Scratch that: I’m confident that we can rise to them better than before, with a greater sense of shared purpose and long-term goals than ever before. Neptune, and all that it represents, is the source of my confidence.

Astronomy shows us the possibility of finding common cause. We don’t have to agree on the specific answers (we never will), but we can agree that an answer is possible — that problems are solvable, and must be solved. That is sufficient.

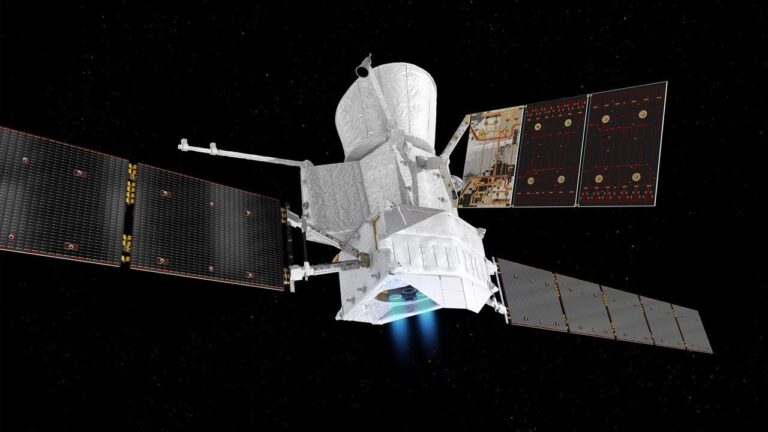

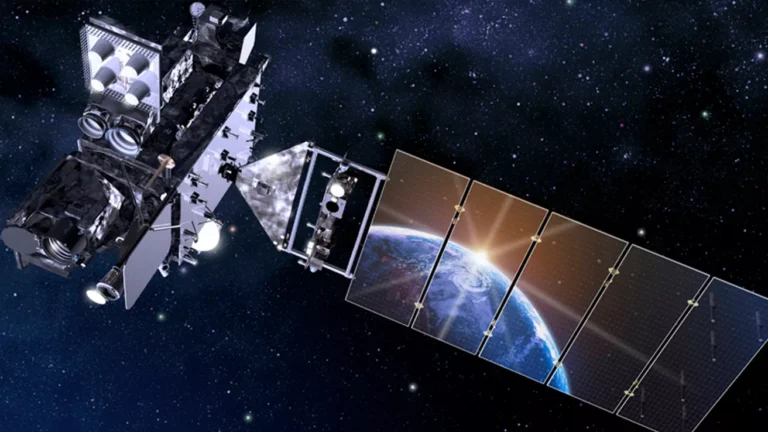

Human curiosity leads to investigation. Investigation leads to knowledge. Knowledge leads to solutions. Sometimes those solutions can seem comically remote from everyday life: the Ingenuity helicopter about to lift off on Mars, the Vera Rubin Observatory taking shape in Chile, the Voyager spacecraft streaking past Neptune. Their remoteness and the audacity of their goals just drives home the message. When we are clear about our goals and when we work together to achieve them, drawing on the greatest resources of our knowledge, we humans are capable of improbably great accomplishments.

I look back to Neptune. I look out to the stars. And I, like you (I hope), look forward to the hard work of building a better future.

A sad closing note: This is the last of my Out There columns for Discover. After 23 years, 6 months, and 6 days, my formal connection to the magazine is coming to an end. But it’s not really the end. I will continue as a contributor to the magazine. Elsewhere, I will be recording my Science Rules podcast, writing for an upcoming TV show, The End is Nye, and sharing my thoughts on Twitter and many other other places.