Key Takeaways:

NASA’s InSight lander has been on the Red Planet for more than 830 martian days, known as sols. That’s a little more than one martian year, or just over two Earth years.

In that time, its Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument has recorded more than 500 marsquakes. Most are small — less than magnitude 2 on the Richter scale — but last February, researchers reported in Nature Geoscience that two of the largest quakes (magnitudes 3.6 and 3.5) had been traced back to a nearby volcanic region called Cerberus Fossae. Now, two more similarly strong quakes (magnitudes of 3.1 and 3.3), detected in March 2021, have been tied to the same region, strengthening the case that Cerberus Fossae is seismically active.

Center of activity

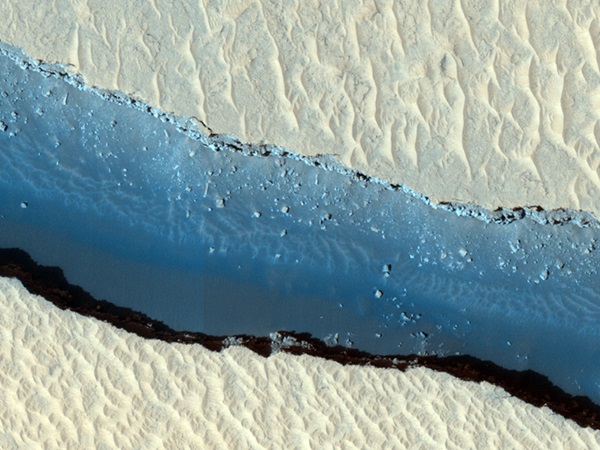

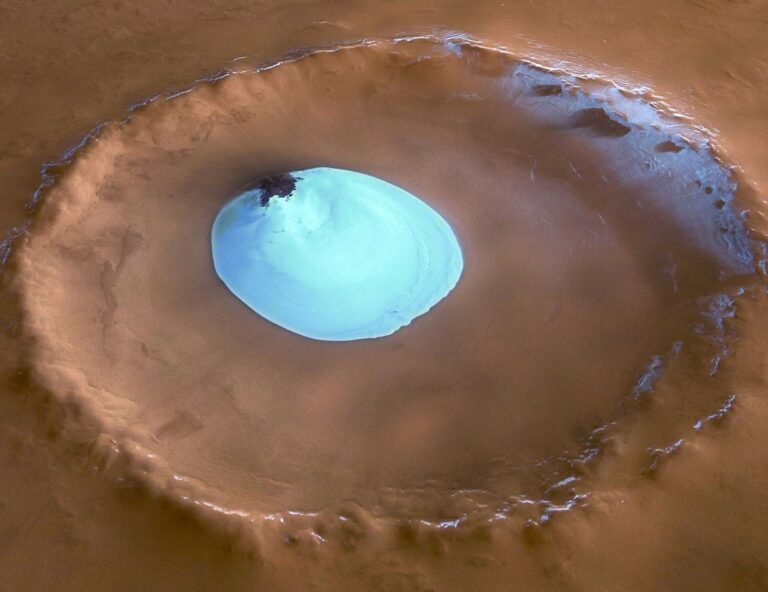

Most of Mars’ surface is a few billion years old. But Cerberus Fossae is different — it is one of the planet’s youngest features, showing evidence of seismic activity within the past 2.5 million years. The region contains deep surface cracks that filled about 10 million years ago with lava, which has since been shaken up by more recent quakes. Researchers have also spotted boulders that appear to have rolled down cliffsides, perhaps knocked loose by those same not-so-ancient rumbles.

The fact that four large quakes have now been traced to this region lends significant evidence to the idea that Cerberus Fossae remains seismically active. What’s more, all of these quakes offer a key window into Mars’ interior structure. That’s because all four marsquakes seem more Earth-like than Moon-like, meaning they traveled more directly from their point of origin through the deeper layers of the Red Planet to reach SEIS.

However, researchers still aren’t sure exactly what is causing the quakes — whether they’re the result of current volcanic activity (albeit beneath the surface) or more passive cooling. Such cooling is believed to cause most quakes on Mars, as the planet cools and contracts, cracking the crust. Detecting more quakes and bigger tremblors will continue to develop our picture of exactly how the Red Planet’s interior behaves today. And SEIS will have plenty more opportunities to catch such quakes, as InSight’s mission has been approved by NASA to continue through December 2022.

Pile it on

March was a busy month for InSight and SEIS. Not only did the seismometer detect two large quakes, but the spacecraft also began working toward one of its next mission goals: scooping up dirt to cover the cable linking SEIS to the lander. This will insulate the cable against temperature swings, reducing noise in its data.

“The seismometer is on the surface and, although protected by a shield, it does pick up wind and is exposed to big daily thermal cycles,” Suzanne Smrekar, InSight’s deputy principal investigator, told Astronomy last year. “Thus, we need to do careful work to remove non-seismic sources using our wind, temperature, and pressure sensors. This slows down publication of results — we don’t want to interpret a glitch as a quake!”

Over the course of a single sol, which lasts about 24 hours and 40 minutes, surface temperatures at InSight’s location can swing between about 32 degrees Fahrenheit (0 degrees Celsius) during the day to –148 F (–100 C) at night. So, covering the cable with dirt will help keep it insulated, allowing SEIS to better hear what it came for: real marsquakes.

The lander began its task March 14, using its steam shovel-like arm to pick up and drizzle a scoop of martian soil over SEIS’ dome. That allowed the dirt to slide down the curved surface of the dome before falling on top of the cable, all without risking the robotic arm interfering with the dome’s seal against the ground. The lander will now continue to drop scoop after scoop of dirt along the cable’s length.

With less interference from wind and weather, researchers hope the seismometer will be even more sensitive to marsquakes in the future, allowing them to more quickly identify real events as well as delve even deeper beneath the Red Planet’s surface to discover what lies within.