Key Takeaways:

- Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet Air Force pilot from a peasant background, was selected in 1960 to become the first human in space, embodying a specific Soviet ideal for propaganda purposes.

- On April 12, 1961, Gagarin successfully completed the Vostok 1 mission, becoming the first human to orbit Earth at an altitude of 203 miles (327 kilometers).

- The Vostok 1 spacecraft, designed for primarily autonomous operation but equipped with a manual override code, concluded its mission with Gagarin safely ejecting and parachuting to the ground after less than two hours in orbit.

- Gagarin's pioneering flight initiated a new era of human space exploration, inspiring numerous subsequent international and commercial space endeavors, though he was prohibited from further spaceflights and tragically died in an aviation accident in 1968.

Last month, three smartly dressed spacemen took time from their training to pause for a moment of reflection. As their greatcoats held back the chill of an early Moscow spring, they laid a splash of red blooms at a grave embedded in the brickwork of the city’s Kremlin Necropolis.

Earlier, in the half-gloom of a tiny office, they surveyed a faded world map, archaic telephones, and a clock perpetually halted at the instant of its former owner’s death. These three space farers — Oleg Novitsky, Pyotr Dubrov, and Mark Vande Hei — surely felt the presence of Yuri Gagarin. And before they left Earth last Friday, they paid tribute to that unassuming hero who, 60 years ago, kicked off a space adventure that will likely never end.

Yuri Gagarin’s early life

Gagarin’s upbringing betrayed little of the icon he would become. Born into peasant stock in the Russian village of Klushino in March 1934, his formative years were brutalized by World War II. He learned to read from old military manuals, pestered his father into helping him build miniature gliders, and found work as an apprentice foundryman. A love of aviation drew him to the Soviet Air Force, where he flew MiG-15 fighters over Murmansk — until he was hired for cosmonaut training in March 1960.

In true Soviet propagandist fashion, the ordinariness of this fresh-faced twentysomething helped him win selection as the world’s first space traveler. According to his backup, cosmonaut Gherman Titov, Gagarin was “a lad who made his dream come true, all by himself.” And while Titov was a poetry-loving teacher’s son, Gagarin represented the ideal communist pin-up: a humble farm boy who rose up from rags to reach the stars.

Yuri flies to space

On April 12, 1961, Titov and Gagarin breakfasted on meat puree and toast with blackcurrant jam. They then donned their orange pressure suits before being bussed to the Baikonur launch pad on the windswept Central Asian steppe. (Legend maintains that Gagarin answered the call of nature by relieving himself against one of the bus tires.) Once the pair arrived at the launch site, and unable to share the Russian going-away tradition of three kisses on alternate cheeks, Gagarin and Titov instead clinked their helmets together in brotherly solidarity.

Inside the spherical cabin of his Vostok 1 capsule (nicknamed the sharik, or “little ball”), Gagarin’s harness was tightened, his ejection seat armed, and his oxygen hose fastened. The spaceship was meant to function autonomously, for fear that separation anxiety might cause the cosmonaut to go mad once in space. But Gagarin was also furnished with a three-digit, not-so-secret code, which would disengage the autopilot and cede control of the craft over to him, if necessary.

At 9:07 A.M. Moscow Time, the rocket — a converted R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile, known as Semyorka, or “Little Seven”— roared to life before climbing toward the heavens. “Poyekhali!” shrieked Gagarin, which translates to “Let’s go!”

Gagarin later recalled “an ever-growing din,” partly muffled by his helmet, as the R-7 climbed higher. The g-forces he experienced during ascent made speaking difficult. His heart rate soared from 66 to 158 beats per minute. By 9:18 A.M., he was safely in orbit. Before his very eyes, a tiny Russian doll comically floated in mid-air, an indicator of weightlessness, which started a tradition that endures to this day. In fact, last week, a toy kitten rode to space with Novitsky, Dubrov and Vande Hei for the same purpose.

Reaching 203 miles (327 kilometers), Gagarin smashed the World Aviation Altitude Record. And as Vostok 1 progressed eastwards, tracking stations peppered across Siberia — from Novosibirsk to Kolpashevo and Khabarovsk to Yelizovo — serenaded him with musical greetings. At Yelizovo station on the Kamchatka peninsula, cosmonaut Alexei Leonov was treated to the first crude television image beamed from space. “I could not make out his facial features,” Leonov remembered, “but I could tell from the way he moved that it was Yuri.”

At 9:32 A.M., as Vostok 1 cut across the South Pacific and headed for the Strait of Magellan, Radio Moscow broke the electrifying news. “The world’s first spaceship, Vostok, with a man on board, was launched into orbit from the Soviet Union.” And although U.S. listening posts were already aware of the mission, the tensions of the Cold War meant the announcement was still incredibly jarring. A struggling nation full of simple farmers (or so many observers in the West thought) had achieved the singular technological triumph of the 20th century.

Less than two hours later, as Vostok 1 plunged back to Earth, Gagarin ejected from the craft and safely parachuted to the ground. The spot where his feet found terra firma, near the small town of Engels, is today marked by a 40-foot-tall (12 m) inscribed obelisk. The pioneering astronaut’s launch pad at Baikonur, known as Gagarin’s Start, also still remains in use.

The beginning of a new era

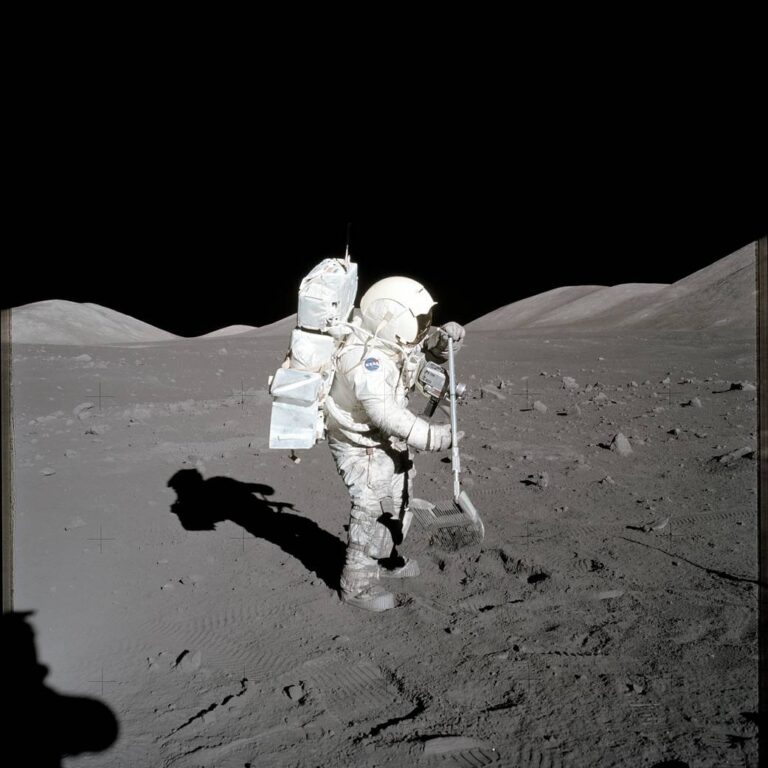

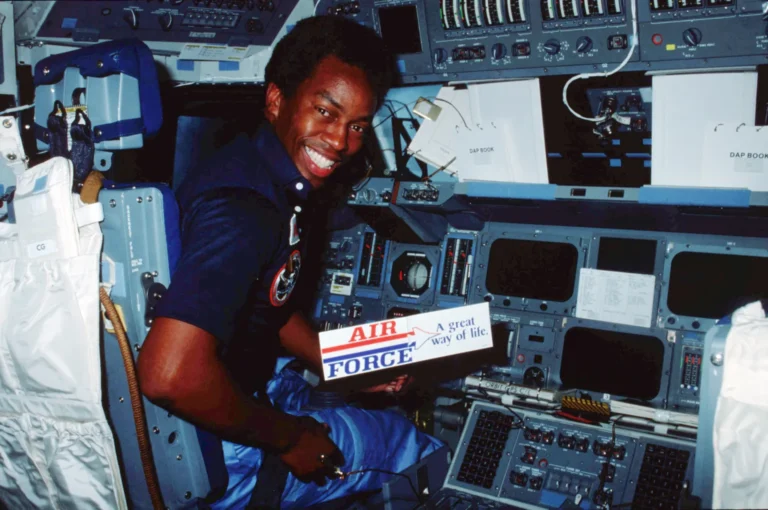

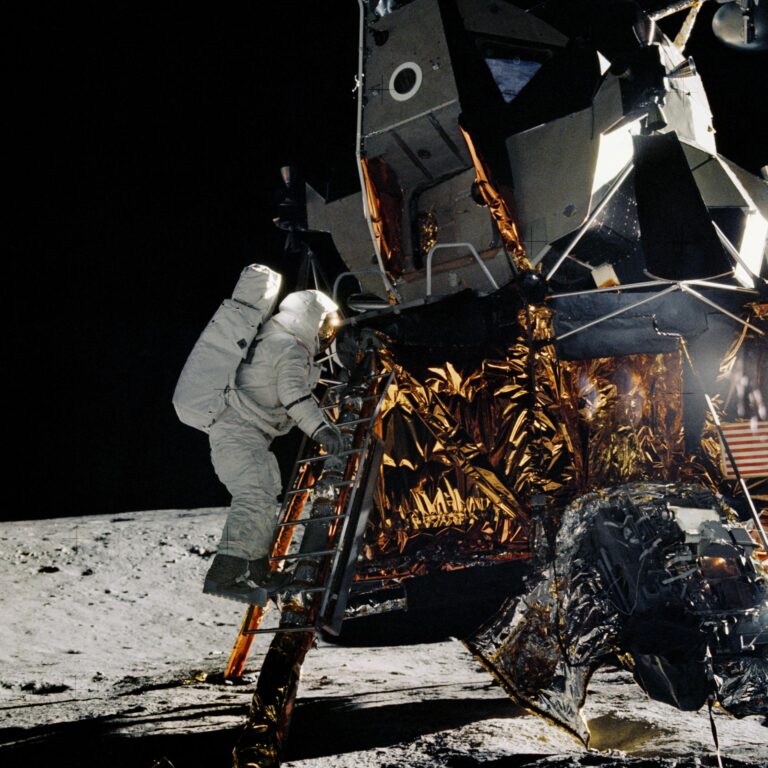

Vostok 1 was a transformative moment. Over the next six decades, 504 men and 65 women representing 41 sovereign nations and a half-dozen religious faiths would venture to space, with their ages ranging from 25-year-old Gherman Titov to 77-year-old John Glenn. Twenty-four of these astronauts have voyaged to the Moon, with 12 of them actually leaving their footprints on the dusty surface. Additionally, 42 men and women have spent more than a year of their lives in space.

Gagarin, however, saw little of this unfolding adventure. Fearing for his life, officials barred Gagarin from a second spaceflight after the Soyuz 1 crash claimed the life of his fellow cosmonaut and close friend, Vladimir Komarov. Gagarin, the highly prized Soviet poster-boy, eventually battled his way back to active-duty cosmonaut status. He might have even flown again, but before that chance presented itself, he tragically died in an airplane crash in March 1968. Gagarin was 34 years old.

Now, as the world prepares for a new space race not based on a simmering Cold War, America’s Artemis Program aims for boots on the Moon by 2024. And later this year, the four crew members of Inspiration4 hope to carry out the first all-civilian spaceflight inside a SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule.

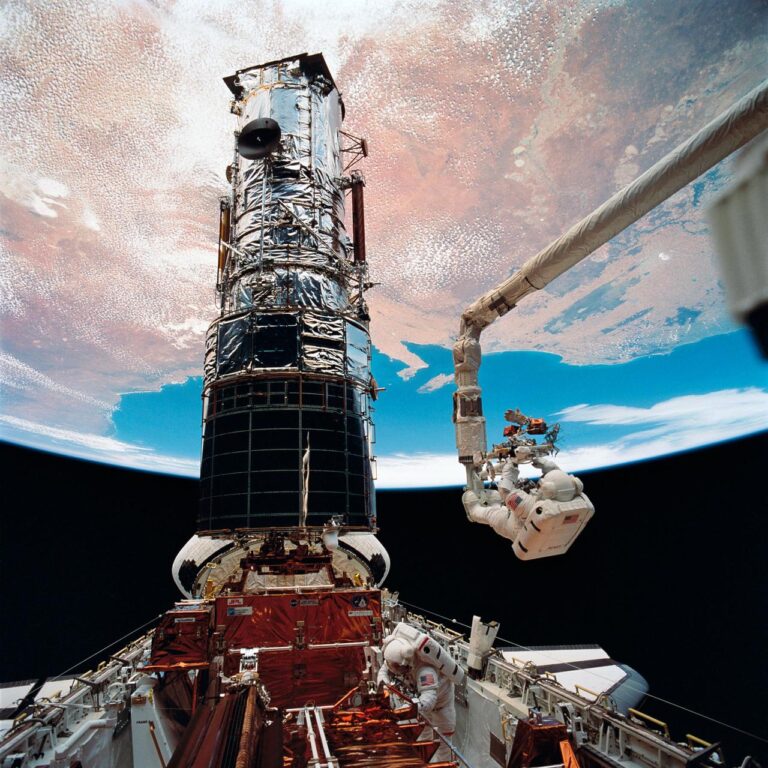

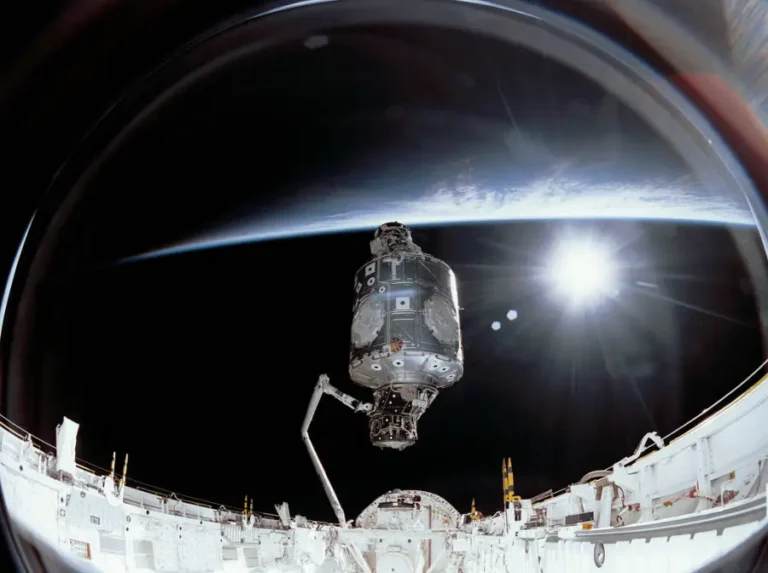

And that’s only the start of the commercial spaceflight to come: Houston-based Axiom is planning private missions (and add-on modules) to the International Space Station beginning in the next few years. Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo draws ever nearer to making suborbital tourism a reality, aiming to commence commercial operations around the start of 2022. And the dearMoon project hopes to see the first-ever lunar tourists fly to the Moon aboard a SpaceX Starship in just two years’ time. Others, including Bigelow Aerospace, envisage inflatable, Earth-circling habitats designed for commercial research. And China and Russia have even outlined plans to collaborate on a Moon base later this decade.

The future seems brighter than ever, if we’re willing to embrace it. And as Gagarin, the man who started it all, once said: “Poyekhali!” Let’s go.