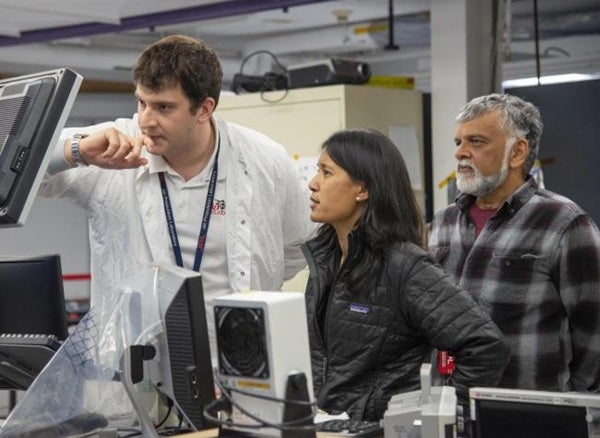

If you want to go flying on Mars, you’re going to need a great flight engineer. When NASA sought out the best person for the job, they selected MiMi Aung. As deputy director of the Autonomous Systems Division at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, she had already tackled fantastically challenging projects designed to enable formation flying in space and high-precision landings on other worlds. Then NASA gave Aung, a Burmese-American engineer, her toughest assignment yet: manage a project to build a helicopter that can fly on Mars.

The helicopter is called Ingenuity. It just traveled to Mars strapped to the belly oft the newly arrived Perseverance rover. And yes, Ingenuity is about to go flying on Mars.

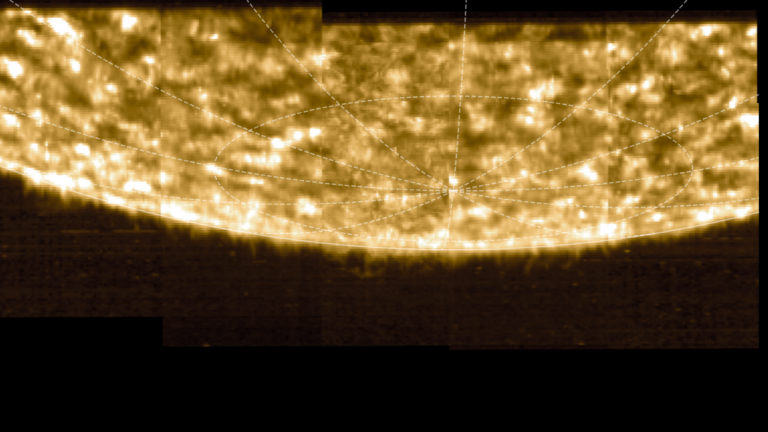

Perseverance has jettisoned a protective shield, exposing Ingenuity to the Mars environment for the first time. The rover is now driving to an open area — a safe place for a test flight — and performing what mission controllers call “reverse origami” to unfold the stowed helicopter and lower it gently to the ground. Sometime on or shortly after April 8, Ingenuity will spin up its wings and attempt liftoff in the extremely thin martian atmosphere.

If successful, it will be the first powered flight on another world. It will almost surely not be the last. Years of determined work by Aung and her team have broken through the challenges to flying on Mars, challenges that many engineers considered insurmountable. Now the techniques and technologies are available for future flyers on Mars. Or maybe above the clouds of Venus, or even high in the atmospheres of the giant planets. The cliche is apt here: The sky’s the limit.

I spoke with Aung about the engineering efforts that went into creating Ingenuity, and what to watch for as it attempts its Wright Brothers moment on Mars. A lightly edited version of our conversation follows. (The second part of the conversation, covering Aung’s remarkable career at JPL, will run in my next column.)

You’ve been working on this project for many years. How does it feel to see Ingenuity finally sitting on the surface of Mars, ready to fly?

I have to keep reminding everybody, you have to look at Ingenuity from the question we started with: “Can it be possible to fly on Mars?” Now that’s no longer a question. We have flown in a really thin, Mars-like atmosphere [in tests on Earth]. That was very difficult job. A lot of challenges along the way to get there.

Then it was no longer a question of whether we could fly. It was like, how? We had to overcome how and build this system. From head to toe, the Ingenuity helicopter is just 1.8 kilograms. That is a huge, huge accomplishment.

So this is not just the first flight on Mars, this is the beginning of a new era of space exploration?

That’s right. Going forward, we are equipped to design lighter vehicles. We now have the equations, we have the models, we have the simulations. We have people connected across NASA and with industry to go on to the future. So that is set in place. Every step going forward is now checking and saying, “This one solution we came up with to build, what are the shortfalls? What were the unknown unknowns? What did we not think about?”

What have you learned already, during the months when Ingenuity was bundled up with Perseverance during the flight to Mars?

The first big thing was when we turned on [the helicopter] in space vacuum. We had already tested our hardware. Due to the light weight, we had to use commercial off the shelf, lightweight components, right? We had tested the helicopter in a Mars-like environment [on Earth], but we were still just simulating. We turned it on and it worked, that’s great — but do you know how much breath-holding there was? But we got through the launch environment and the true space vacuum, so we’re good there.

Then there was descent and landing, same thing: “Is everybody okay?” The day after landing, when we turned on, our thermostat circuit started working again. Now we’re working in the Mars atmospheric environment! We know that the vehicle arrived at Mars the way we packed it and launched it, so we’re a lot more confident.

Can you walk me through the milestones happening right now as you prepare for Ingenuity’s first-ever flight on Mars?

We already know are working the way we want to on the rover. The next big moment is when we deploy, starting now. This is where we work with the Perseverance rover team: JPL and Lockheed Martin that did the Mars helicopter delivery system and AeroVironment, as well as NASA Ames and NASA Langley. We all worked together to put it onto the rover.

During deployment, again, we want to know: Are we learning anything new in the Mars environment? The drop is probably the biggest moment for us. That energy budget that we did, that little thermal shell that was trapping the carbon dioxide. Did we calculate the energy right for the Mars temperatures that we modeled? So this is a cross section of thermal and power and electronics, and all of the modeling there is. It’s all about survival now. How well did our hardware survive? After drop, do we survive the first night?

In the best-case scenario, you would get five test flights on Mars, is that right?

Yes. We have up to five flights planned. We have a 30-day experimental window, and then we’re done. We fly on a three-day cadence, so it’s not like we can fly three days in a row.

What limits you to five flights? If Ingenuity’s hardware exceeds your expectations, could you keep going?

The fixed limit is time. We have 30 days. As you know, Perseverance has its own incredibly important primary mission. Days on Mars are extremely valuable, so I’m very appreciative of getting those days. We’ll be packing those 30 days. Then you need get to get back to the primary science of the Perseverance rover’s mission.

As an engineer, what will you be watching for during the Ingenuity test flights? You talk like you’ve already completed the hardest parts of the mission.

You absolutely got it. To all to us, we know this vehicle. We’ve flown the [test] vehicles so many times, the tens and tens of times, in flight chambers. We stressed the engineering development model and the flight model and tested it? How did it survive the trip? The main thing is that we want to learn. If anything unexpected happens, how do we get the information so that we can feed that information into the next generation of [flight] vehicles? That’s what drives us now.

You’re already thinking about new flying vehicles for Mars or other worlds?

Absolutely. There is something deep that drives you when you do so much work for so many years, right? For us, that drive is adding an aerial dimension to space exploration. Not just a spacecraft in space or rovers on the surface: We’ll also have the ability to fly around in the way we want to. Adding that aerial dimension will be useful in many ways. Rovers need scouts that can see far ahead, high-definition scouts that can get a clear picture of where you are. Astronauts in the future will want to explore places they can’t get to.

Now, what is it possible to build? How can we fulfill the vision?

Can you go bigger than Ingenuity? Could you have giant helicopters zooming around on Mars?

We’re at a 1.2-meter diameter system [Ingenuity’s flying rotors] because that’s the largest that would fit in the Perseverance rover, and that’s the largest mass they could give us. For future helicopters, we’re looking at a three- or three-and-a-half meter diameter [rotor], and a mass of about 15 kilograms. Anything larger than that, the floppiness of the system comes into play [and makes the helicopter unstable]. A system like that could carry a one-kilogram payloads. That’s the vision.

What kind of science could you do with a one-kilogram payload flying around on Mars?

Oh, the science community has lots of ideas about instruments! They are also coming up with [potential] payloads that are getting lighter and lighter. And maybe we could get to a two-kilogram payload. Unfortunately, Mars just doesn’t have enough atmospheric density to make it safe to fly anything bigger.

You’re adamant that Ingenuity is not a “drone.” What’s wrong with that word?

I often get getting teased about not using the word “drone” for the Mars helicopter, but I feel very strongly about it, for the following reason: We are just getting over the fundamentals. This is a pathfinder mission to show, How do you build it and how do you operate it? We’re breaking the paradigm, but it has a lot further to go. Once [flying machines] become a norm — which is our dream, which is why we work so hard — then yes, there will be Mars drones at that point.

There is another flying machine already in the works, the Dragonfly mission that will fly on Titan in 2036. Do you collaborate with that team?

Dragonfly is quite different. It’s a large system, a spacecraft-class instrument, because there is so much atmosphere on Titan. However, testing the aerial vehicle is still a first-time event. How do you spin for the first time without vibrating and shaking apart? Everything that we had to solve, Dragonfly will also be doing that. It will be fantastic to share the lessons we’ve learned about how to the aerial vehicle and how do you simulate the [alien] flight environment on Earth.

Where else might we go flying in the solar system?

Every planetary object that has atmosphere is a potential target. When Dragonfly was selected, it was fantastic because, yes, there’s going to be another aerial vehicle! Yes, it really can become the norm. Anyplace we send landers or rovers to, why not have a flying machine accompanying it? That’s my dream. If you go to Mars, why not? Why not put multiple helicopters on [a future rover], multiple copies? By then we can call them drones. It’s a very powerful exploration tool.

I hadn’t even thought about that. You could have swarms of flying robots.

Absolutely! You can go to all dimensions. You could make it large and add telecommunication systems so you can communicate directly to Earth, then you don’t have to go to the rover or relay with orbiters. Or you can go small and send a whole bunch of them. If you go small, you can build a very small, extremely clean system [sterilized to avoid contaminating Mars or other worlds]. You could explore sensitive areas. Or we can send swarms that share information and take data simultaneously across different areas.

It opens up a whole new way of exploring.

Since you are always looking forward – what is the next challenge for you?

I’m working on a proposal to NASA on Venus mission called VERITAS. A decision from NASA [on whether to fly VERITAS] comes in July. So I’m at Mars with the helicopter, and I’m at Venus in parallel as we’re speaking.

It’s time to go back to Venus. We haven’t been there in 30 years. Our proposal is a whole global investigation of the surface and the interior. Venus holds so many answers to rocky planet evolution. It’s fundamental, and it’s our nearest neighbor. It’s started so similar to Earth in mass and the size.

You really have an amazing job.

Thank you so much. It’s really fun to tell this story. It’s like a big reward after all the work you do.