Key Takeaways:

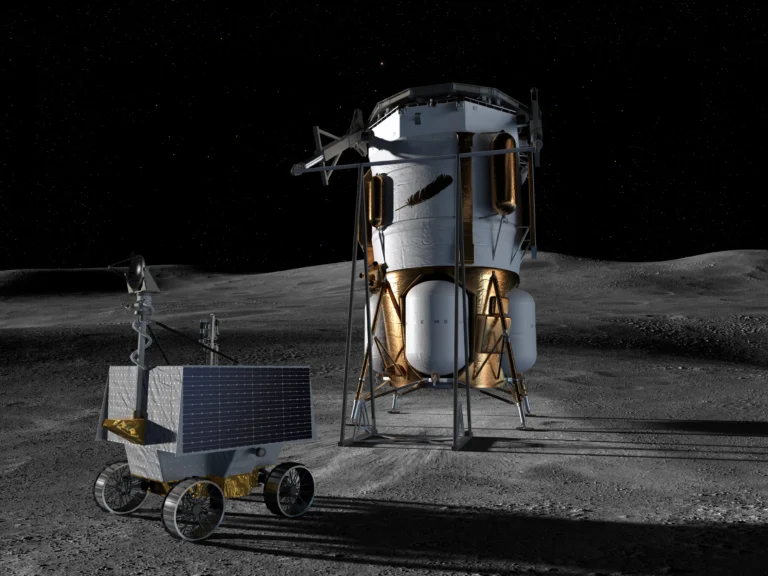

NASA’s Artemis program currently aims to put astronauts back on the Moon by 2024. However, a NASA report released in September 2020 outlining this goal also states that 2024 “is the most ambitious date possible.”

Ambition is admirable, but reality sometimes steps in. Delays are common (and likely) for many reasons, ranging from safety considerations to technological problems to ever-evolving budget and policy changes. That’s why it was no surprise that in a February 2021 interview with Ars Technica, Acting NASA Administrator Steve Jurczyk said putting boots on the Moon by 2024 may no longer be a realistic goal.

With delays may come embarrassment, but pushing back Artemis might also have a more tangible and potentially dangerous consequence: increased risk of exposure to dangerous extreme space weather for astronauts and spacecraft. According to a new paper published May 20 in Solar Physics, delaying crewed Moon landings into the late 2020s could increase the chances that lunar astronauts will be exposed to more extreme space weather and its damaging effects.

Why the weather in space matters

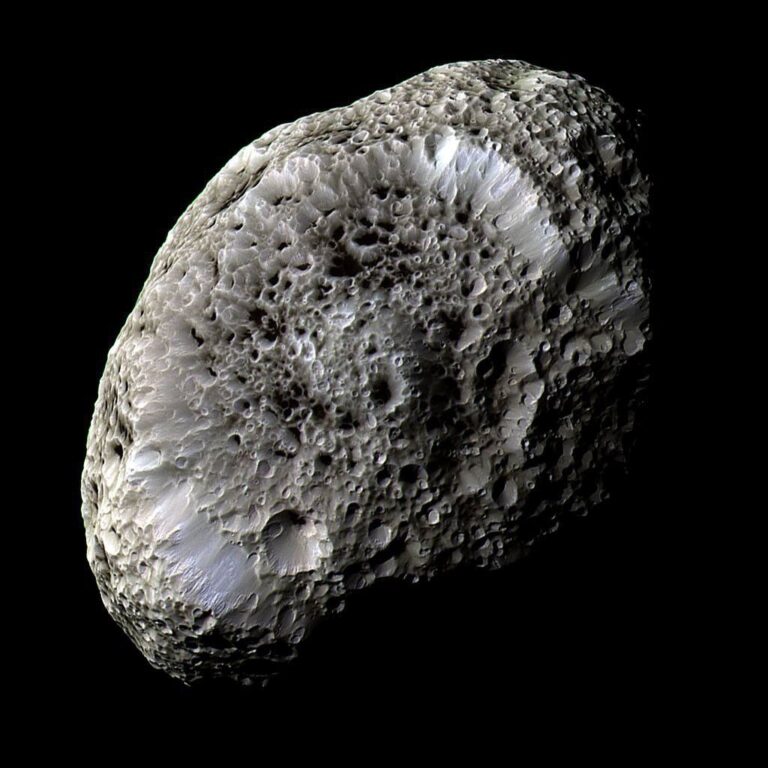

Space weather is the result of activity on the Sun. From the steadier solar wind to short-lived flares and outbursts of material called coronal mass ejections, this activity sends energetic particles racing through the solar system. On Earth, our atmosphere shields us from the effects of mild to moderate space weather. But the largest and most extreme solar storms are different.

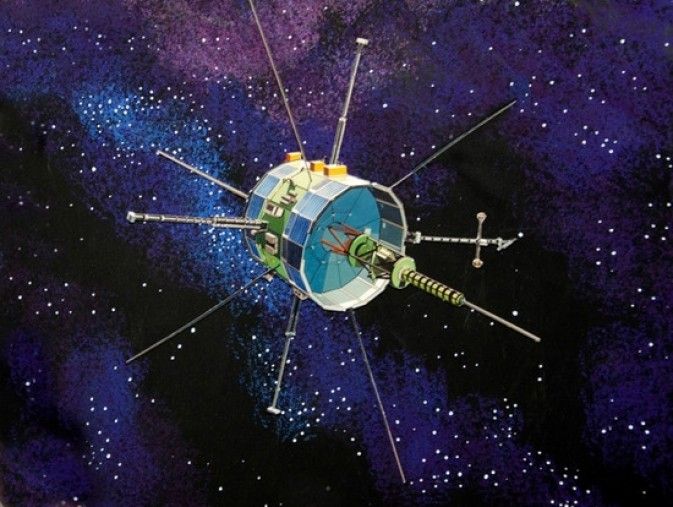

Powerful space storms can disrupt satellite communications and earthbound power grids. They can also pose serious and cumulative health risks to astronauts above Earth’s protective atmosphere. Those humans currently aboard the International Space Station (ISS) — located some 250 miles (400 kilometers) above Earth’s surface — must retreat inside the most heavily shielded parts of the station for safety when a strong storm passes through.

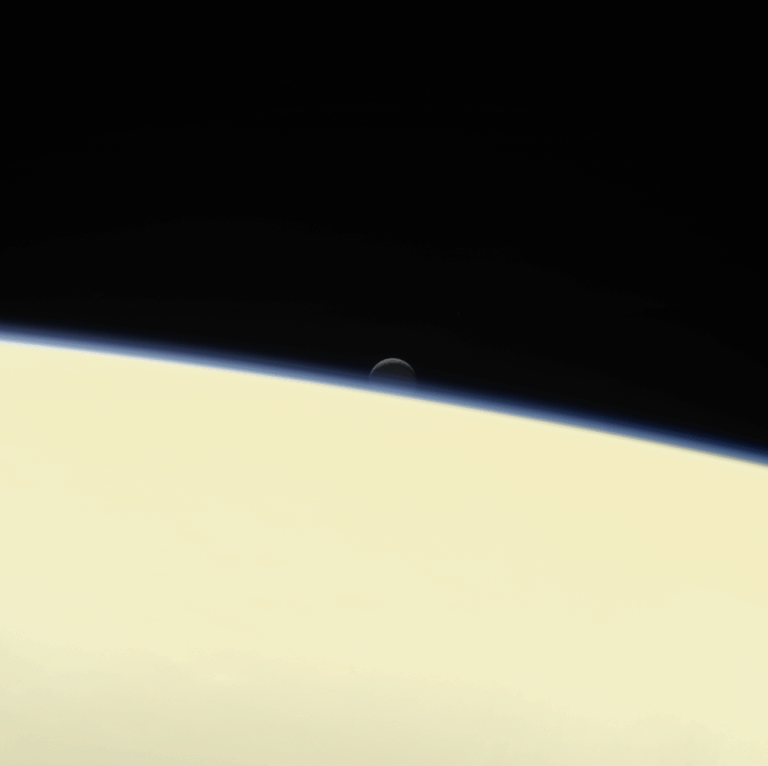

But even astronauts aboard the ISS have an advantage over those en route to or on the surface of the Moon. The ISS orbits within Earth’s magnetosphere, which helps to deflect or slow down some incoming particles. However, the Moon spends most of its time outside this bubble, eliminating that additional protective factor. That ups the risk for Artemis astronauts with respect to events that could affect astronaut health or damage spacecraft, preventing them from navigating space or communicating with Earth.

Like the ISS, their spacecraft will include more heavily shielded areas where astronauts can retreat for added protection. Additionally, NASA does have plans in place to help bolster protection for astronauts on the lunar surface during a major space storm: They’ll have astronauts pile supplies and even lunar soil around their shelters. That will put more mass between them and any incoming energetic particles, reducing the risk.

But it won’t eliminate the risk entirely, especially during the most extreme events. NASA currently plans to fly two mannequin torsos on the uncrewed Artemis 1 mission to determine just what kind of radiation environment astronauts will experience. (In addition to the solar wind and space weather events, cosmic rays from outside the galaxy also zip through space, further adding to the radiation background.) But unless there happens to be a major solar storm during that time, this experiment won’t take into account conditions during such an event.

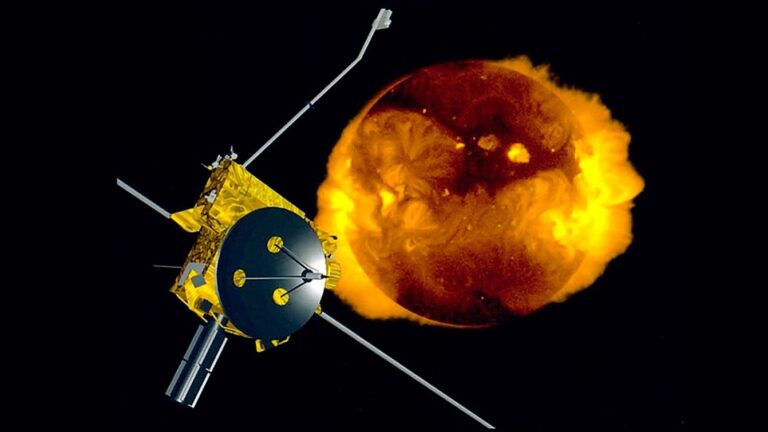

A look at solar activity

Astronomers know that the Sun has a regular 11-year cycle driven by changes brought on when its magnetic field flips about once a decade. The Sun recently entered cycle 25 in December 2019.

Each cycle has a maximum and a minimum period of activity, and astronomers have long known that outbursts and space weather are in general more likely to occur during a solar maximum. Researchers also know that moderately disruptive space weather events occur more frequently during solar cycles that yield more sunspots (which themselves are related to the Sun’s magnetic field and are more common during solar maxima).

Still, for all scientists know about the Sun, they previously didn’t know much about the timing of when our star generates the most extreme space storms. It was unclear whether the strongest outbursts are random or follow the same known patterns, or seasons, as other space weather.

In their new paper, the authors have finally answered that question. By analyzing 150 years of space weather records, they found that more extreme space weather events do indeed follow the same patterns as less extreme events. So, extreme space weather is more likely to occur during solar maxima and during cycles with more sunspots.

Furthermore, their analysis shows extreme space weather events occur earlier in even-numbered solar cycles and later in odd-numbered solar cycles. This could be, they think, related to the overall polarity of the Sun’s magnetic field during each subsequent cycle — i.e., which way is north and which way is south. That polarity flips during each solar maximum, so it starts out pointing different ways during even- and odd-numbered cycles, which begin at solar minimum.

Based on this new information, that means if human activity on or around the Moon is pushed back into the latter half of the 2020s — during odd-numbered solar cycle 25 — the risk from extreme space weather will increase. While extreme storms are less likely between now and 2026, the researchers say, the interval between 2026 and 2030 will carry a higher likelihood of big events that mission planners may have to consider.

Knowing for sure that extreme space weather is more likely during the latter half of the 2020s is already a big step toward improving astronaut safety and the chances of mission success. In this case, forewarned is definitely forearmed.