Citizen Science Salon is a partnership between Discover and SciStarter.Org.

NASA is recruiting citizen science volunteers to help astronomers discover exoplanets hidden in observations from one of its space telescopes.

A pair of citizen science projects, Planet Hunters TESS and Planet Patrol, are asking users to help sort through images from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and separate out potential exoplanet signals from those of planet impostors. Meanwhile, another project called Exoplanet Watch is tapping amateur astronomers to help follow up on new planet discoveries using backyard telescopes.

It’s an opportunity for volunteers to play an important role in astronomy’s exoplanet gold rush, where thousands of worlds have been discovered in recent decades. The projects will be featured as part of an event on May 21 called Planet Palooza during the upcoming CitSciCon, put on by NASA, SciStarter and the Citizen Science Association. The event is hosted by Phil Plait, AKA the Bad Astronomer.

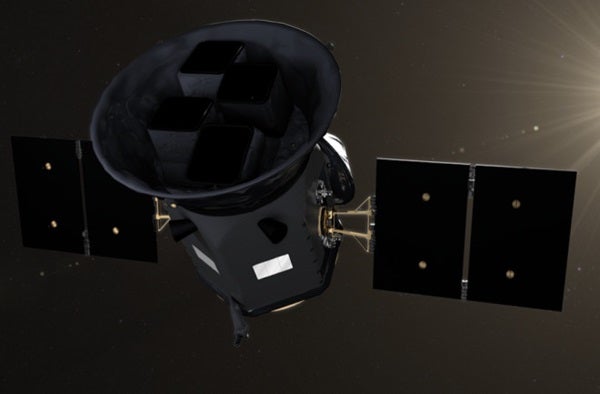

NASA’s TESS mission

In 2018, NASA launched TESS as a next-generation space telescope designed to find Earth’s cosmic neighbors. The mission was a successor to NASA’s iconic Kepler spacecraft, which found more than 5,000 potential exoplanets.

Like its predecessor, TESS’ mission is to discover new alien worlds by watching for dips of light in more than 200,000 bright, nearby stars. Astronomers call these dips “transits.” And during its initial two-year mission, TESS managed to image nearly the entire night sky and make nearly 100 confirmed new exoplanet discoveries. The space telescope has also turned up thousands of potential exoplanet candidates thanks to clever algorithms and sophisticated hardware. But confirming these candidates isn’t easy.

The initial planet candidates are found by an algorithm that scans TESS’ images. Then, astronomers enlist a second, highly effective algorithm to confirm the results of the first program. But even these cutting-edge computer codes get tripped up sometimes, leaving huge numbers of potential exoplanets that need to be confirmed manually.

“With TESS, the number of targets to look at now is in the millions, and even after you run the vetting software, the number is still in the millions,” says NASA astronomer and citizen science officer Marc Kuchner.

Most of those millions of targets are not exoplanets at all. But NASA still needs to do a basic analysis to find out if it’s noise, a binary star, or something more interesting. Astronomers can’t handle such a large job on their own, so citizen scientists have stepped in to take up the task.

Citizen science in astronomy

Turning to citizen science volunteers for this kind of help isn’t unusual in astronomy these days. Modern astronomical surveys commonly use computer algorithms to discover new objects in their vast archives of images. But astronomers know that computers can’t catch everything. And the human brain is often still better at identifying new planets than a computer.

“The datasets we’re getting for astronomy are just so huge right now,” says Kuchner, who also works on Planet Patrol. “Citizen scientists have already discovered half of the known comets and most of the long-period exoplanets. They’re making discoveries left and right. I think that astronomy projects are realizing that they need to work with the citizen science community to make the most of their data science.”

Citizen scientists have already helped discover hundreds of new exoplanets, thousands of brown dwarfs, plus other strange objects, like Boyajian’s star.

Volunteers with Planet Hunters TESS have made over 250,000 classifications of astronomical objects. And so far, some 5,000 Planet Patrol volunteers have made more than 400,000 image classifications. In fact, they’ve already analyzed all the project’s uploaded data, so the researchers are working on uploading new images for analysis.

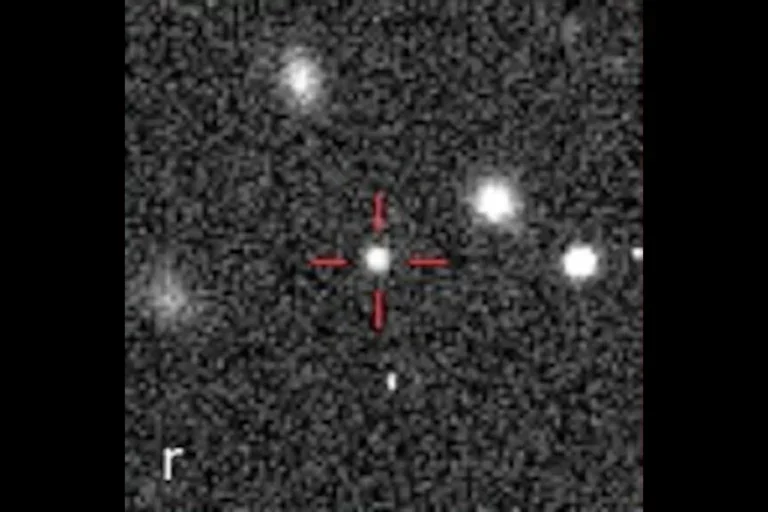

In Planet Patrol, users are asked to look at an image and apply some basic categorization, like whether there’s a bright spot in the center of the image, more than one bright spot, or no well-defined bright spot.

“Our automated algorithms are correct around 90 percent of the time,” says Planet Patrol’s project leader, Veselin Kostov, who works as a researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and the SETI Institute. “[But] sometimes, they struggle with weak signals.”

According to Kostov, the algorithms can get tripped up by false-positives, which look like the signals from exoplanets but are actually other natural phenomena. Common sources of confusion include stellar eclipses and occultations, where one star passes in front of another, as well as instrument artifacts.

Amateur astronomers hunting exoplanets

By the time the TESS mission is over, NASA expects the space telescope will have discovered thousands of confirmed exoplanets relatively close to Earth. Of those, some 300 are expected to be exoplanets the size of Earth or slightly bigger. Then, after the James Webb Space Telescope is launched in the next few years, it will follow up on those finds in much greater detail, giving astronomers unprecedented insights into other worlds that might just be like Earth.

“The heyday of TESS science is yet to come,” says Kuchner. “The major goal is for these planets to be followed up by the JWST. I think that’s going to really mine the most science out of these TESS exoplanets. Each one is intrinsically interesting because it’s nearby — often they’re in star systems that you’ve heard of.”

Where a typical planet discovered by the Kepler space telescope might be thousands of light-years away, the ones discovered by TESS might be just 100 light-years away. And that proximity means JWST will be able to look at the chemical fingerprints of these worlds, including their atmospheres, searching for potential signs of life. So, a world discovered by Planet Patrol users might end up being one that astronomers soon study in much greater detail.

Exoplanet Watch is also hoping to make it easier to follow up on exoplanet candidates. The NASA citizen science project is starting out geared toward having amateur astronomers, as well as colleges and universities, observe transiting exoplanets with small telescopes. The citizen scientists observe their own exoplanets, analyze and upload their own data, then upload it to the American Association of Variable Star Observers so they can be shared with astronomers.

Those small telescope observations can pin down a planet’s orbit, which then helps researchers better calculate the world’s size. Beyond confirming and discovering new exoplanets, the observations should also make for more efficient use of time on pricey space telescopes, like JWST.

And while the opportunity to help discover entire planets might seem like plenty of incentive to get involved, Kuchner says that, in his experience, citizen scientists are often inspired to keep going by benefits they never initially expected.

“It changes people’s lives when they get to meet new people who are doing science,” Kuchner says. “They get to realize that they’re not the only person who’s interested in it. There’s other people like them. Then, they make their first discovery and they get to be a piece of the action.”

Volunteers who want to get in on the planet-hunting action can tune in to the Planet Palooza event on May 21 for a demo of Planet Hunters TESS. The NASA project scientists will also be on hand to answer questions.