Key Takeaways:

When I went to my first Star Trek Convention back in 2013 in Boston, it was because Sir Patrick Stewart was supposed to be there. I had even gotten my then-fiancé a ticket for the event specifically so he could meet him. In the end, Stewart cancelled. But I don’t think meeting him could compete with what I will forever remember as one of the greatest moments of my life: Nichelle Nichols taking my hand in hers while we took a photo together.

Recognizing a young interracial couple — me, a Black woman, and my fiancé, an Asian American man — Nichols, the woman who comprised one half of the first interracial kiss on television, made the decision to arrange us for the photo. First, she had us stand on either side of her. Then she held our hands up in a statement of power.

Years later, I still feel emotional about that moment, which is a testament to Nichols’ thoughtfulness and awareness of her capacity to change the world. And today, a new documentary about how Nichols used that power begins streaming on Paramount+.

By now, many of us have heard the story of how Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. approached Nichols and told her about the significance of her role as Lieutenant Uhura. King told her that Star Trek was the only show he allowed his children to watch because her role as the chief communications officer showed them a vision of a world where Black people go to space. One might expect, therefore, that playing Uhura is Nichols’ greatest cultural contribution.

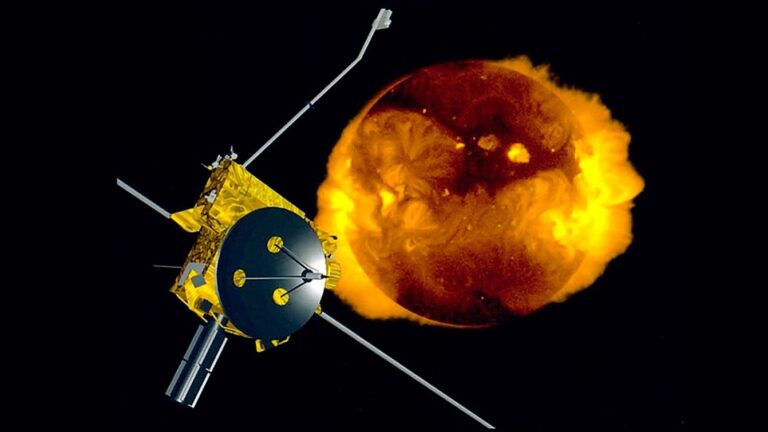

But Woman in Motion is unique in its emphasis, focusing not on Nichols’ impact on screen, but rather on the way she changed the U.S. space program through a partnership with NASA.

When she held my hand, Nichols did not know that I was one of under 100 Black American women to earn a PhD from a department of physics, or that at the time I was a Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Postdoctoral Fellow in Physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In hindsight, I didn’t fully understand the power of the moment either. As a child of the 80s, I grew up with the NASA Space Shuttle Program, and at MIT, I worked in the Ronald McNair building, named for the MIT alumnus and physicist who became one of the first Black astronauts. McNair, one of only a handful of Black people to ever go to space, was recruited by Nichelle Nichols for NASA. In other words, Nichols had helped open the doors that I was walking through every single day.

An interrupted career that sparked others

Woman in Motion, which is named for Nichols’s STEM education company (one of the first to be run by a woman, we learn), begins with the Nichelle Nichols origin story. In Chicago, she was the only Black girl in all-white ballet classes, and also the child of a man who believed she would go on to become a star. Along the way, we learn that Nichols can sing, too (and viewers who stick around through the credits will get quite a treat on that front). Nichols began her career with the legendary Duke Ellington and his band, thinking she’d eventually spend her life on Broadway.

Instead, a chance casting by Gene Roddenberry in an episode of his show The Lieutenant would change the course of her life. The episode never aired; the network refused because it centered on race. Roddenberry was angered by this and began to think about how he would push further on issues of racism and equity. Not long after, he hatched the idea for Star Trek. Nichols was brought in to try out for the role of the communications officer. Not only did she get the role, she was also responsible for the character’s name, Uhura — a play on the word “uhuru,” which means “freedom” in Swahili.

Nichols tells viewers, “I became essentially who I became through Gene Roddenberry.” Though the original Star Trek series would only last for three seasons, Nichols also relays, “Star Trek interrupted my career.” She had, in fact, been thinking about leaving the show when Rev. King approached her at a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People event in Los Angeles.

Over the years at various Star Trek conventions, I’ve heard her tell this story, somewhat mournfully. I always remember it as an example of the myriad ways that Black folks are called on to sacrifice for the next generation. Nichols ultimately gave up her Broadway aspirations because Black kids needed to see her in space.

After the series ended, Nichols went on to become an ambassador for NASA, an opportunity that was, in part, facilitated by one of the first Star Trek conventions. There she met Jesco von Puttkamer, a senior manager at NASA responsible for promoting the astronaut program, thus beginning a partnership that included a four-month recruitment campaign. At the start of the recruitment campaign, there were 1,500 applications for the astronaut program, with 100 from women and 35 from minorities. By the time she was finished, there were 8,000 applications; 1,649 were from women, and 1,000 were from minorities.

Among the astronaut recruits were Ellison Onizuka, who went on to be the first Asian American and first person of Japanese descent in space; Judy Resnik, the second woman and first Jewish person in space; and Ronald McNair, the second African-American and third Black person to reach space. All three were barrier breakers. All three passed away in the 1986 space shuttle Challenger accident. Seeing Nichols’s grief over their losses is one of the most difficult parts of the documentary. I wept with her.

Missed opportunity

Notably, the documentary does not discuss how many people fell into both categories, “women” and “minority.” This is a symptom of a larger production problem: Almost everyone who appears in the documentary besides Nichols herself is a man, and when women do appear, almost all of them are white. The total amount of on-screen speaking time for Black women who are not Nichols is under one minute. There are no non-Black women of color, either.

Nearly the entire production team also seems to have been men. This appears to be reflected in the storytelling, where we sit through descriptions of von Puttkamer’s comments on Nichols’s legs, as well as commentary from various astronauts and actors about how attractive they found her. At no point do we see new interview footage of a Black woman scientist or astronaut, though three have been to space. The absence of a conversation with the first — Mae Jemison — is especially notable because Jemison has credited Nichols with encouraging her to pursue a career as an astronaut.

In this sense, the documentary fails. Although it celebrates the significant achievements of a Black woman, Black women as a group are more broadly invisible. We briefly see actress Vivica Fox at the beginning, then hear comments from U.S. House Representative Maxine Waters 30 minutes in. That’s it. No connections are drawn to the Hidden Figures, or those of us Black women scientists who grew up knowing we could be scientists because of Nichols. In my view, this was a significant missed opportunity that also fails to capture the fullness of Nichols’s legacy.

It is, of course, valuable to recognize that white women also extensively benefited from Nichols’ outreach efforts, but to include no Black women historians, scientists, or science communicators is to miss out on an important piece of her legacy. Part of what Nichols contributed, both through Uhura and in the wake of her creation, was a vision of Black women crewing a technical enterprise. How great it would be to see this reflected in the storytelling about that voyage.

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein is an Assistant Professor of Physics and Core Faculty Member in Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of New Hampshire. Her first book, The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey into Dark Matter, Spacetime, and Dreams Deferred, is out now.