Key Takeaways:

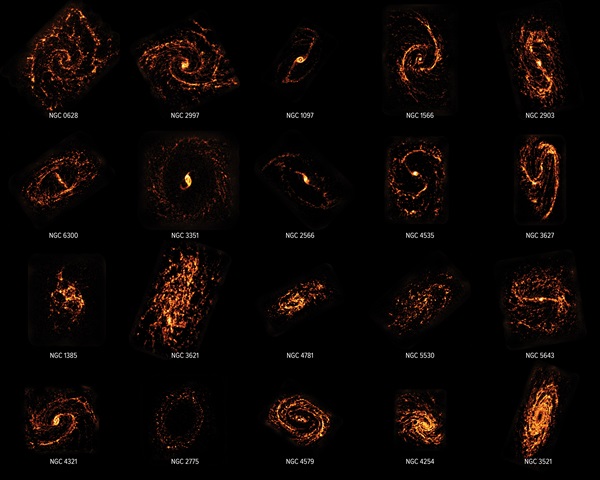

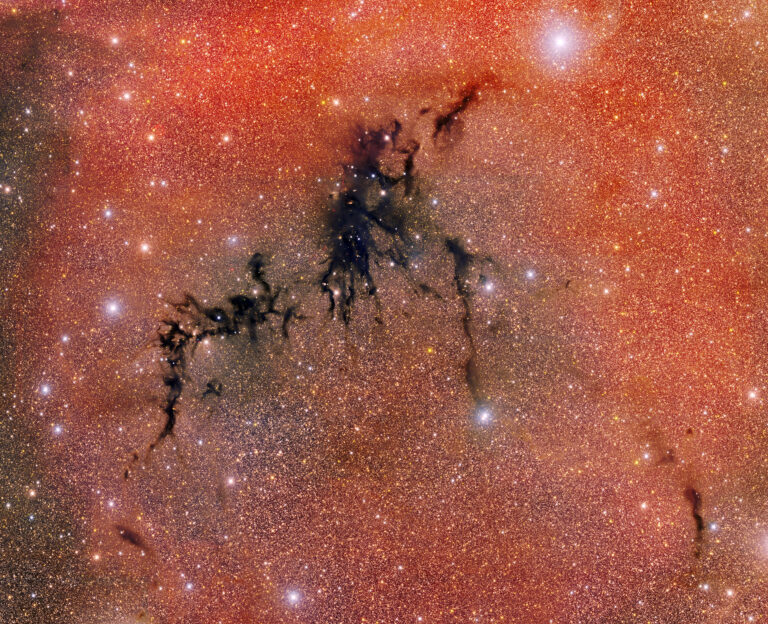

Stars are born in celestial factories known as molecular clouds. Dark, dense, and cool, these clouds absorb light at visible wavelengths, making them hard to comprehensively survey with optical telescopes. But thanks to the ALMA radio telescope in Chile, astronomers were able to map these stellar nurseries in stunning detail, observing 90 nearby galaxies at radio wavelengths.

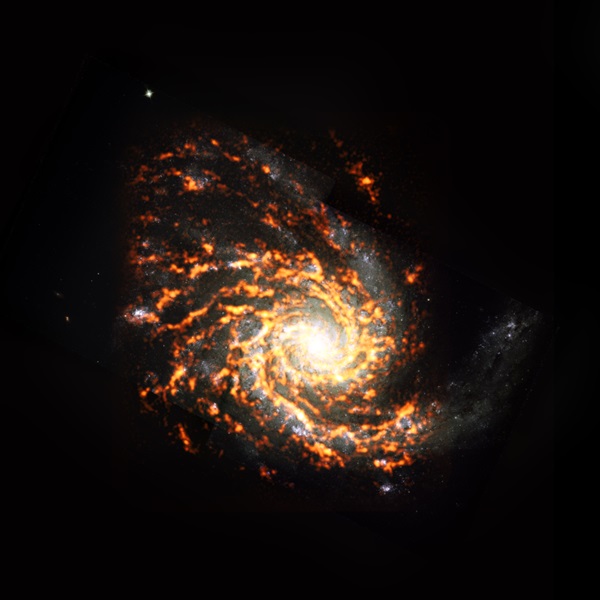

The result is an unprecedented census of the demographics of molecular clouds: A total of 40,000 examples were identified in total (20 times more than previously known), with their locations pinpointed to a dizzyingly diverse array of galaxies. As seen in the image above, these stellar factories trace out a ghostly outline of star-forming activity in their galaxies, like cities blazing at night seen from space, separated by vast obscurities of darkness.

The survey, known as PHANGS (short for Physics at High Angular Resolution in Nearby GalaxieS), was made possible by the high resolution of ALMA.

“This is the first time that we have ever taken millimeter-wave images of many nearby galaxies that have the same sharpness and quality as optical pictures,” said Adam Leroy, an astronomer at Ohio State University, in a press release.

The survey results were presented Tuesday at the online summer meeting of the American Astronomical Society, and detailed in a preprint uploaded to the arXiv in April.

Now that the census is in, astronomers can begin investigating the data in earnest. Preliminary analysis shows that these molecular clouds are not uniform across the local universe, as some had previously assumed, but instead populate diverse neighborhoods shaped by their host galaxies.

“We already see that clouds in high density regions and in the centers of galaxies are denser, more massive, and more turbulent than clouds in … galaxy outskirts,” said Annie Hughes, an astronomer at the Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planétologie in Toulouse, France, speaking at an online press conference.

Understanding how galaxies shape their own history of star formation — and vice versa — will help astronomers refine their models of galactic evolution, she added.