Key Takeaways:

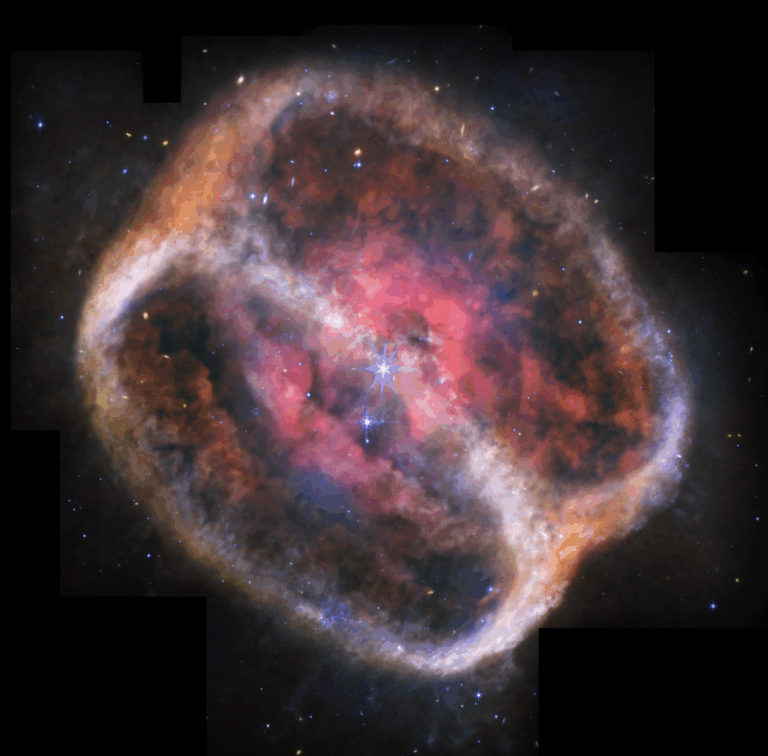

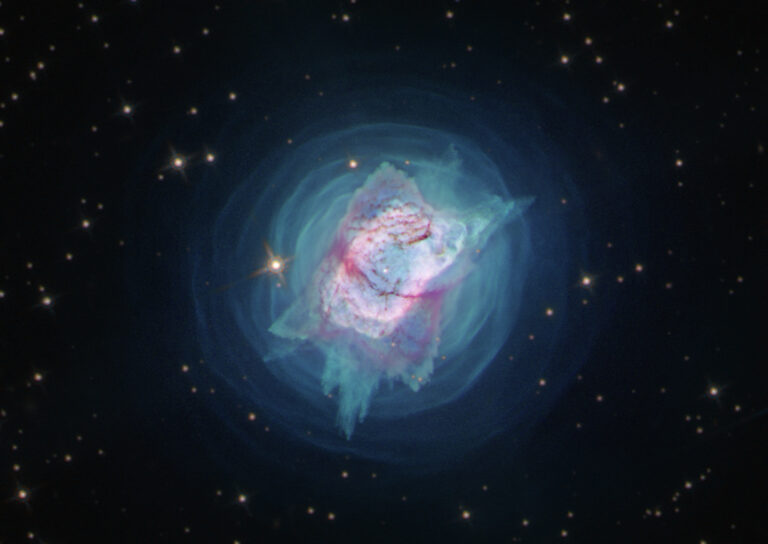

In the year 1054, a new star appeared in the constellation Taurus. The faint speck of light brightened rapidly, soon outshining other imposing stars in the northern sky. In a matter of days, the star’s brightness peaked. It stayed visible for weeks, even during the day, before it started to dim and slowly fade into nothingness.

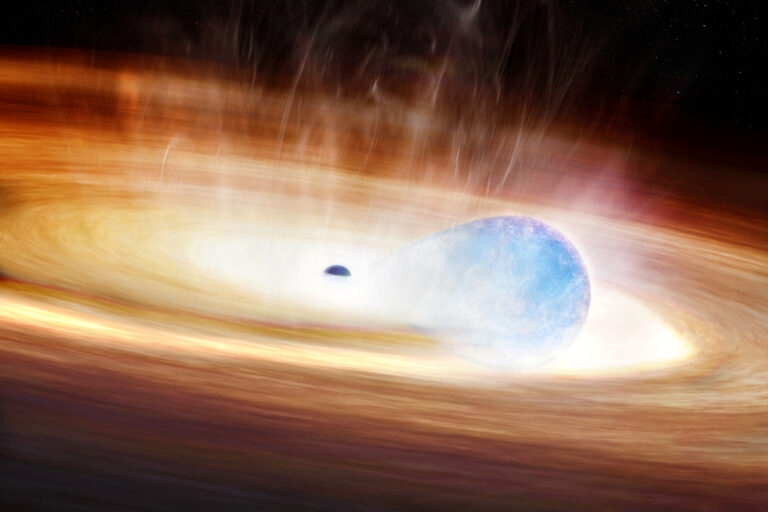

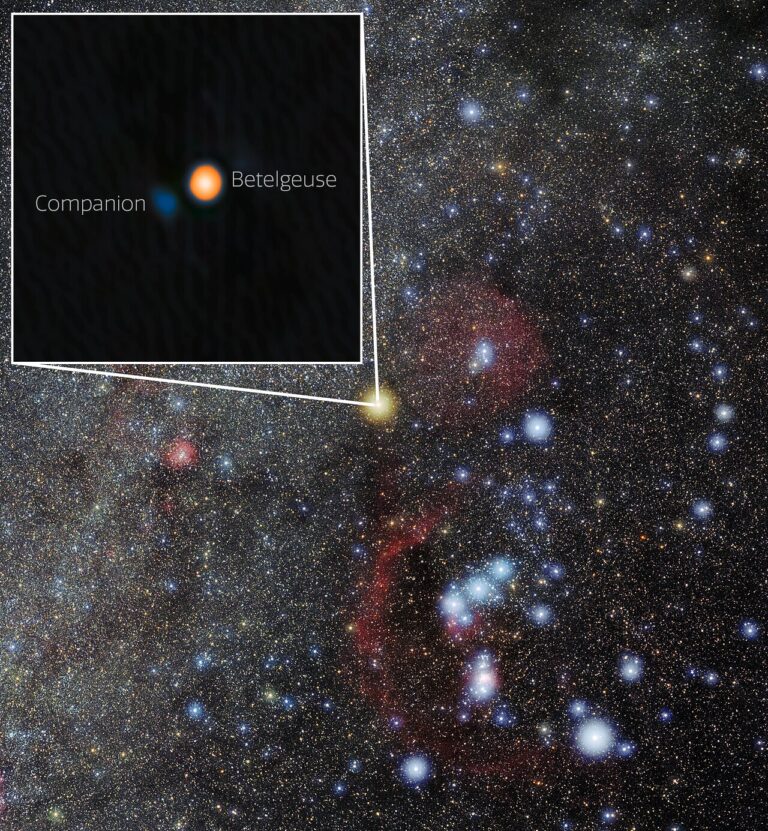

The baffling star that embellished the sky in 1054 was in fact a supernova, just one of many transient sources appearing in the sky — that is, objects related to events that occur on short timescales, often changing visibly from night to night. Taking many forms and colors, some transients originate in the Milky Way, while others are objects exploding in galaxies far away.

The interest in transients has never been greater. Many surveys of the sky are discovering new sources at unprecedented rates. In 2019, astronomers reported about 20,000 newly discovered transient objects at visible wavelengths, about 100 times greater than a decade prior.

This firehose of data has the potential to transform astronomy and provide insight into subjects ranging from dark energy and dark matter to the evolution of our solar system. But it also presents unique challenges — how to make sense of the data, and how to follow up on it.

When a trickle becomes a flood

Surveys find transients by imaging the same parts of the sky with a certain cadence. A sequence of images reveals new sources and their change in brightness over time. Such information is not always enough to classify a transient. For that, one would need to obtain a spectrum of the transient, and perhaps even observe it at infrared, X-rays, or radio wavelengths.

However, the era when astronomers could follow up on every object that came along has already gone away — there are now simply too many being found. “We’re already for many years in a regime when you have to make choices [about] what you classify spectroscopically and what you don’t, and that depends on science,” says Daniel Perley, a researcher at Liverpool John Moores University in the U.K. It is telling that the community obtained the spectra for only about 10 percent of transients discovered in 2019.

Perley’s goal is to take stock of the bright transient population detected by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), which has been one of the most productive transient surveys since it began operating in 2018, spotting supernovae and fast-moving asteroids alike. By limiting the study to the brightest sources, it is feasible to take useful spectra of every object in the survey and learn, for example, how many supernovae of a certain spectral type explode in the universe.

Scientists interested in particular types of transients, like those exhibiting an especially red or blue color, have to take a different approach. For them, the initial limited amount of information determines whether a transient merits a long follow-up observation campaign. Their decision to use additional resources on a transient is based on experience, yet it always carries a bit of risk — you don’t really know a transient until you take that additional observation.

Searching for anomalies

That experience from ZTF and other transient facilities will come in handy once the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile comes online in a few years. “The Rubin Observatory is going to increase the discovery rate by two orders of magnitude, from 10,000 per year to a million new supernovae and transients per year,” says Ashley Villar, an assistant professor at the Pennsylvania State University. “This is a breaking point for our field.”

The flood of transients discovered by the Rubin Observatory will include specimens that current surveys rarely find, such as very distant supernovae or very faint supernovae exploding in nearby galaxies. Scientists expect that the observatory will also discover completely new types of transients.

According to expectations, less than 0.1 percent of all transients discovered by the Rubin Observatory will get extra attention. Developing reliable techniques to recognize interesting transients in the clutter is therefore of paramount importance.

Villar plans to use a neural network, a type of machine learning, to search the data for anomalous transients with unanticipated properties. But she expects researchers will employ a wide variety of strategies to work with such massive datasets. “Some people will lean towards totally automated queue systems that just rank targets, look at their observability, and make some intelligent choice,” says Villar. “Others will want to have humans in the loops, looking at the data, asking simple questions, and deciding from there.”

Some kinds of transients stand out based on the wavelengths of radiation they they emit — which can range from gamma rays to radio waves — and how their brightness changes over time. That means that searches tailored towards these particular kinds of transients can avoid the classification and follow-up problems encountered in searches at optical wavelengths.

For instance, fast radio bursts — immensely powerful blasts of radio waves possibly caused by flaring magnetars — are immediately distinguishable. “You can already tell from the first discovery that it’s a fast radio burst, approximately how far away it’s coming from, and its energetics,” says Emily Petroff, a radio astronomer at the University of Amsterdam.

Avoiding interference

While the transient field is flourishing, a threat looms on the horizon: the rise of light pollution across the electromagnetic spectrum. For instance, radio telescopes searching for transients are sensitive to emissions from phones, cars, airplanes, and various kinds of satellites. And the problem is getting worse. “We’re constantly playing the game of cat and mouse with new sources of interference that we’re finding at our telescope sites,” says Petroff.

So far, optical astronomers have been able to escape the pollution by observing from remote and dark oases. However, the recent upsurge in bright commercial satellites — like SpaceX’s Starlink constellation — is already disturbing observations. The anticipated fleet of satellites, which numbers in the tens of thousands, profoundly worries the community. The Rubin Observatory, in particular, has been developing a multi-pronged approach to mitigate its impact, working with SpaceX to reduce the reflectivity of its satellites and also developing algorithms to remove satellite trails from images.

It is easy enough to point a telescope at the sky. But to make sense of all the blinking lights, both cosmic and artificial, astronomers are adapting and developing clever techniques. And it is worth it, because one of those lights could turn out to be something unlike anything we have seen before.