Key Takeaways:

Some Moon missions get all the glory.

Apollo 8 was the first to orbit the Moon. Apollo 11, the first to land. And Apollo 17 was the last crewed mission to the lunar surface — for now. Of course, each mission was a crucial milestone. But collective memory can be fickle.

Which brings us to Apollo 15. By the time this mission landed 50 years ago, public interest in and political support for the Apollo program had waned. Ironically, that waning interest also made Apollo 15’s pioneering role possible. Budget cuts had forced the cancellation of several future missions, which meant that NASA’s scientifically ambitious expeditions — classed as J missions — had to occur earlier than anticipated. So, Apollo 15 was the first of the J-class crews.

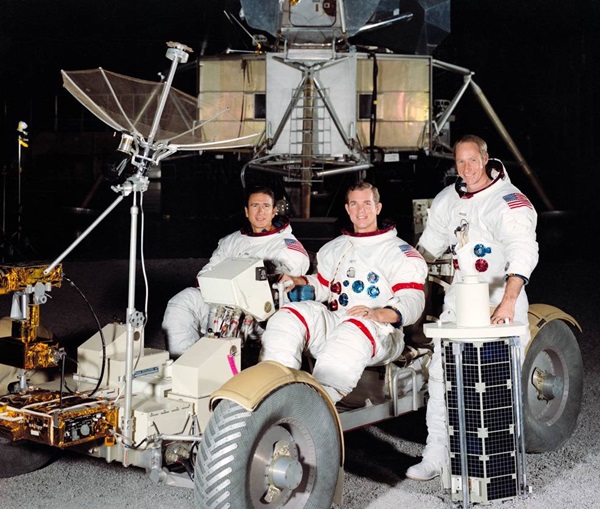

Apollo 15 launched July 26, 1971, and the Falcon Lunar Module (LM) landed July 30, staying on the surface until Aug. 2 with moonwalkers Dave Scott and James Irwin (the commander and Lunar Module pilot, respectively). Meanwhile, Command Module Pilot Al Worden orbited in Endeavour. The crew splashed down Aug. 7.

Worden ran first-ever science experiments, while Scott and Irwin explored the edge of the sublime Hadley Rille (more than 1,000 feet [300 meters] deep) and the lower reaches of the soaring lunar Apennine mountains (with some peaks 3 miles [5 kilometers] high). Apollo 15 brought back reams of data and about 170 pounds (77 kilograms) of Moon rocks — almost twice the haul of Apollo 14 — including a famous sample that changed the course of lunar science. The reason for the increased haul of rocks? The first-time use of a Lunar Roving Vehicle, which vastly increased the range of surface exploration and the materials returned.

As with every Apollo mission, there are stories small and large that take us behind the mission. Here are some of those gems, exclusively via Astronomy.com.

Where’s the LM?

Surprise — the original Apollo 15 Lunar Module is not on the Moon! At least, not the one NASA had planned on sending. Once the mission was upgraded to a science-heavy J designation, the original Apollo 15 Lunar Module — designated LM-9 — was scrapped. Or, more accurately, set aside. Today, visitors to the Apollo Complex at the Kennedy Space Center can see LM-9 set in a colorful educational display showing two astronauts exploring the Moon’s surface beneath the nose of a ceiling-mounted Saturn V.

Science as exploration

The early Apollo program had been criticized for focusing on engineering goals to the detriment of learning more about the scientific mysteries of the Moon. That changed with Apollo 15. Boston University geologist Farouk El-Baz, who was a force in preparing astronauts for scientific lunar exploration, tells Astronomy about some firsts associated with this mission: “It was the first mission to have a rover allowing us to send the astronauts to collect surface samples from the landing point — a mountain front that was different from anything we had sampled. It was also the first mission to have a Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay [in the orbiting service module] that carried a host of sensing instruments and a high-resolution camera that was 7 feet long and could see down to one-meter [resolution] on the Moon. [And] the high-latitude location [of the Command Module’s orbit] allowed us to examine a large swath of the Moon’s surface — with much of the lunar terra [highlands] on the farside and of several maria on the near side — including sensing their chemical composition.”

But Apollo 15’s exploration program might not have been all so high-tech. According to a 1971 NASA booklet called “On the Moon with Apollo 15,” one researcher had suggested using a kind of crossbow to shoot a sampling tool across the mile-wide Hadley Rille. Attached to a cord, the sample could then have been pulled back in.

Hello, Earth

While in lunar orbit, Worden stayed busy running the cameras and ensuring that first-ever SIM was working. But he also wanted to emphasize the global nature of lunar exploration. Every time he returned from radio silence behind the Moon he greeted Houston’s Mission Control with the phrase “Hello, Earth. Greetings from Endeavour,” in multiple languages, including the Arabic that El-Baz had taught him. The phrase would stay with Worden who, after returning to Earth, eventually wrote the first and only book of poetry by an Apollo crew member called, appropriately enough, Hello, Earth: Greetings from Endeavour. In one poem, he asks, “Could it be a Lunar flight/Is one small step towards home?”

Before his death in 2020, Worden said in an interview that his poetry came from a very private place, but in both his public talks and his poems, he contemplated “a universe I wasn’t expecting … We will never see the end of the universe. We don’t have a clue what this is all about. We have to get out there and see what’s there.” He considered the survival of our species “the greatest imperative.”

Practice makes (mostly) perfect

Apollo’s science training coordinator, William Phinney, wrote in a NASA field training book that Apollo 15’s surface science package weighed a whopping 1,200 pounds (540 kg), three times more than on the previous mission. This meant science training had to go into overdrive. For example, field practice would go on to almost always include “a simulated backroom with CapCom [capsule communicators] and scientists. For the first time all the CapComs were scientists and that would also be the case for the actual mission,” he wrote. Field training became elaborately planned to include various simulated traverses analogous to the actual lunar sites. Crews spent more time in classes and lab settings.

And their enthusiasm was a notable change from the indifference of some earlier astronauts. That enthusiasm was sparked in part by their inspiring teacher, Caltech’s Lee Silver, with whom the Apollo 15 crew “developed a wonderful rapport,” according to Phinney.

Scott, for one, was thrilled, especially with field training expeditions: “I loved them. I loved to be outdoors. It was a chance to get away from the simulators and other hardware for three days at a time, a chance to have a few beers in the evening after a hard day in the field,” he says. Eyes sparkling, he adds that his favorite field site was in Iceland due to its Moon-like appearance and isolation.

Farouk El-Baz says Worden took his training to heart as well: “The training particularly of Al Worden was a great pleasure, because he soaked [it] all in. He would give up much of his free time to get more of my instruction. By the time he was ready to fly, he could rumble the name of features he would fly over during a given segment of the flight. And he showed his ability during the first orbit by conveying the names of the craters he was going over — stunning the guys at Mission Control.”

A wonderful dramatization of the Apollo 15 training — and how NASA altered its approach to teaching its crews geology — appears in the sometimes artfully inaccurate episode “Galileo was Right” of Tom Hanks’ HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon.

Despite their training, the Moonwalkers could not be prepared for all the rigors of what Irwin called “the ultimate desert.” During the mission, both he and Scott became dehydrated during a moonwalk because “we had not selected sufficient cooling in our liquid cooled underwear.” Consequently, their heartbeats were irregular when they ascended back to lunar orbit.

Grover

Apollo 15’s pioneering lunar rover is still on the Moon. But if you are in Flagstaff, Arizona, visit the U.S. Geological Survey’s Astrogeology Science Center building and check out the display in the lobby. There you will find one of 10 custom-built Grovers — makeshift training vehicles the astronauts used to practice driving the real thing. They trained with the Grover at multiple locales, including the volcanic cinder fields not far from Flagstaff.

Fun facts: Each Grover cost $1,900, took three months to build, and was far heavier than the actual rovers that went to the Moon (which would have collapsed in Earth’s gravity). According to the USGS, the jury-rigged Grover was so cheap in part because technicians scavenged parts from old cars — the steering mechanism is from a Renault, the wheels from an Olds Tornado — and they even used landing gear from a B-26 bomber.

The first sculpture on the Moon — and the first feather

While Apollo 14’s Alan Shepard thought it would be fun to hit a golf ball or two while on the Moon, the Apollo 15 crew had more serious things in mind. Scott and Irwin placed on the lunar surface a small figurine called Fallen Astronaut and a placard with the names of deceased astronauts. For audiences back on Earth, Scott dropped a falcon feather and hammer. They landed on the surface at the same time, proving that Galileo was right about the acceleration of objects under gravity.

Did they look back?

Irwin wrote that as a child in Pittsburgh he “felt even then the pull of the Moon.” But did the astronauts of Apollo 15 ever look at the Moon through telescopes after their return?

Before his death, Worden told me, “I had one of those ball telescopes, Edmunds…” I interjected, “Astroscan.” He exclaimed, “Yes! I loaned it to a guy and never got it back.” After, he didn’t bother to get a new scope.

Scott remembers looking at the Moon from Arizona’s Kitt Peak Observatory — all the astronauts did this — and says he had a little telescope in London when he lived along the Thames. Now, he has “too much going on” and doesn’t have a telescope anymore. (Scott is the only surviving member of the crew.)

But Worden, Scott and Irwin all looked back in their respective memoirs: Falling to Earth (co-written with Francis French), Two Sides of the Moon (co-written with Alexei Leonov), and To Rule the Night (co-written with William Emerson).

Windows into time

The samples brought back from Apollo 15 look back as well — to the origin of the solar system and the mysteries of the Moon’s formation, features, and characteristics.

According to Tim Swindle, the outgoing director of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona, “Based on fragments in the samples of soil from Apollo 11, scientist John Wood had proposed that the Moon was molten at one point and then a mineral called anorthosite, which is both light in color and light in density, floated to the top to make the original crust, which we still see as the light-colored highlands today. Scott and Irwin saw a bit of light-colored material exposed on a rock and, as they examined it in more detail, they realized that it was almost pure anorthosite. That rock, later numbered 15415, became known as Genesis rock, and although it is not the oldest sample returned from the Moon, it’s an excellent example of the early crust.”

This first sample of the primordial highlands helped confirm the magma ocean hypothesis proposed by Wood and others.

But that’s not all. “The diversity of the samples that were collected by the Apollo 15 astronauts was astounding,” says Ryan Zeigler, the Apollo Sample Curator at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. Not only did they nab the famous Genesis rock but, among other samples, Scott and Irwin collected “the first sample of pyroclastic glass from fire-fountain eruptions and the first deep drill core from the Moon,” which was nearly 8 feet (2.4 m) long.

Apollo 15 points us to the future as well, says Kate Burgess, a geologist with the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. She explains that “the training of the astronauts that allowed them, as former test pilots, to recognize the importance of [the] Genesis rock while on the Moon” demonstrated the importance of geological field training, which “is probably among the most lasting legacies, as I know it is influencing the training of the current Artemis class.”

While Apollo 15 may be 50 years in the past, its achievements and consequences continue to resonate.