Key Takeaways:

The rocky planets

Mercury is the most non-weather planet of all. The solar system’s first planet’s atmosphere is closer to a vacuum than Earth’s protective sheet, making the daily forecast perennial black skies and a Sun that looks twice as large as our own view. With a 59-day rotation barely outpacing its 88-day orbit, and virtually no gas to exchange solar heat via churning wind cells, one side of the planet fries sunny-side-up throughout the mercurian year while the other freezes.

Venus, too, boasts a stable forecast, but hardly an inviting one. The planet’s atmosphere is mostly carbon dioxide (CO2), causing nightmarish global warming. The abundant CO2 traps most incoming solar radiation, producing surface temperatures around 900 degrees Fahrenheit (480 degree Celsius). If they manage to not get crushed by the atmospheric pressure, human visitors would be speed broiled. A hardened Soviet Venera lander from 1978 holds the surface survival record at just under two hours. Venus is most famous for being the hottest planet in the solar system and the closest in size to Earth, but our sister world is also the only one that rotates east to west — possibly due to tidal friction that caused the atmosphere to drag and reverse the planet’s original spin.

Like Mercury, Venus bakes mostly on one side since a day on the scorching world is longer than its year — though Venus does manage to fit two Sun rises during its 225-day year. The additional ingredient of atmosphere results in violent heat exchange and tornado-force winds at the middle and upper levels. While evenly distributed greenhouse heating keeps winds calm at the surface, the imbalance of solar radiation at higher levels whips the Venusian atmosphere around the entire planet in just four days. A decade ago, Europe’s Venus Express orbiter recorded a 33% jump in these speeds. Combined with recent claims of a microbial biosignature called phosphine in upper-level sulfuric clouds, interest in our nearest neighbor have increased tenfold. NASA and ESA have since announced a trio of missions to visit Venus.

The Martian atmosphere features aspects of both Venus and Mercury. It, too, is mostly carbon dioxide, but is extremely thin — a mere one percent of Earth’s. Sandstorms and ice caps are all that remain of the liquid water and the much thicker atmosphere that once prevailed on the Red Planet. Because Mars has an axial tilt similar to Earth’s, its ice caps seasonally wax and wane. After two decades of NASA rovers and orbiters tracking sandstorms, photographing wind devils, and sampling water ice, Mars is a prime candidate for the discovery of extraterrestrial life. Astrobiologists believe the remnant delta created by an ancient lake in the Jezero Crater, where the Perseverance rover now treks, may have once been a cauldron of microbial activity.

The gas giants

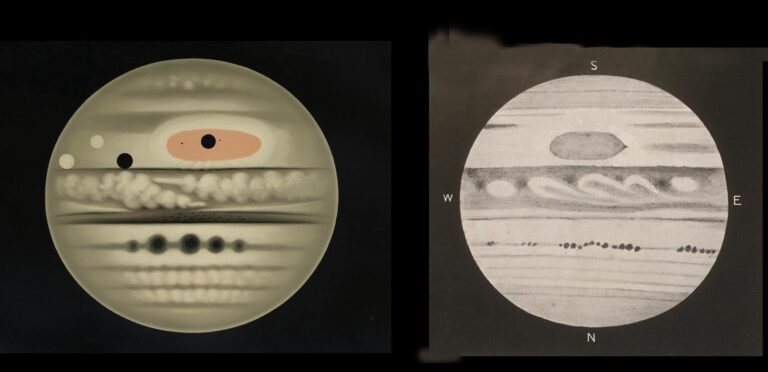

Beyond Mars, solar system weather gets wild. The most obvious case is Jupiter’s brilliant red-and-white banding, crowned by the Great Red Spot, an immense storm larger than Earth (and thus easily visible in backyard telescopes) that has lasted for hundreds of years. In 2000, it spawned a smaller storm, Oval BA, aka Red Jr. Both rotate counterclockwise in the southern hemisphere, indicating they are high pressure systems — not hurricanes.

While the Great Red Spot posts rotational speeds exceeding 270 mph (430 km/h), astronomers recently discovered a stratospheric polar express over three times as fast beneath the aurorae ringing Jupiter’s poles. Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to track the spectral fingerprint and movement of hydrogen cyanide — a molecule left in the wake of the Shoemaker-Levy comet impacts of 1994 — the team unveiled the blazingly fast jets this spring. If as the winds are part of a giant vortex, as the team suspects, it would be up to four times the size of Earth and over 550 miles (900 km) high. As co-author Thibault Cavalié stated in a press release, “a vortex of this size would be a unique meteorological beast in our solar system.”

Saturn, too, has polar aspirations. Like Jupiter, its atmosphere is hydrogen-rich with ammonia-ice clouds. In 2012, the Cassini spacecraft produced vivid photographs of a remarkable hexagonal jet stream — first detected in the 1980s by the Voyager probes — shooting point to point around the planet’s north pole.

That was seven years after it produced equally remarkable imagery of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, which is far more interesting to astrobiologists. Nitrogen-rich with a dollop of methane and ethane, Titan is the only moon in the solar system with clouds and a dense atmosphere — four times heavier than our own. It is also the only world besides Earth that features liquid on the surface despite temps hovering near –300 F (–184 C).

Cassini also detected a subterranean saltwater ocean, lakes and seas of liquid methane near the poles, and vast stretches of arid dunes ringing the equator. And when Cassini launched the Huygens probe to Titan’s surface in 2005, photos revealed a fantastical landscape of misty haze, river channels, and dunes.

With an axial tilt of 27 degrees, Titan has seven-and-a-half-year seasons and methane rainstorms that are thought to flood polar rivers in summer. NASA’s eight-rotor Dragonfly helicopter will land at Titan’s equator in 2034 in search of life. The dense atmosphere (as compared to the ultra-thin air NASA’s Ingenuity helicopter deals with on Mars), should enable it to fly northward in a series of hops covering over 100 miles (160 km). Based on seasonal observations from Cassini, NASA forecasters predict calm weather.

“We think of Titan as a real-life laboratory where we can see similar chemistry to that of ancient Earth when life was taking hold here,” says astrobiologist Melissa Trainer, Dragonfly’s deputy principal investigator.

The ice giants

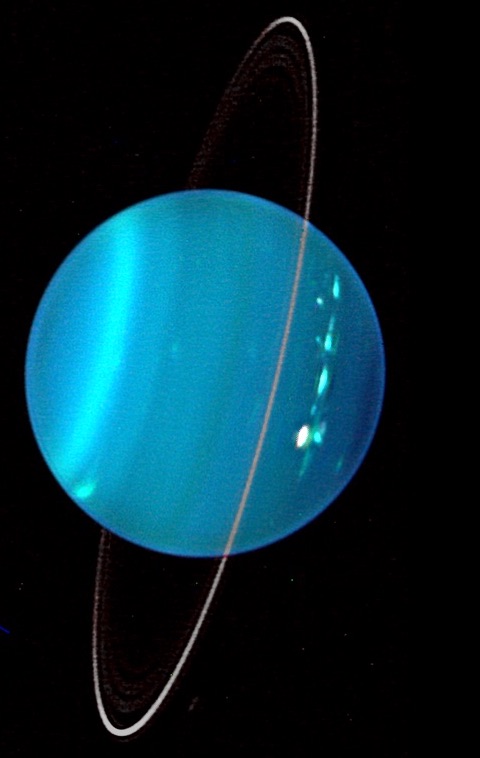

Uranus and Neptune are, by contrast, somewhat neglected, with only one probe (Voyager 2) having ever flown past. Not much is known about weather on these last two planets except what can be deduced from Hubble photos and laboratory simulations.

Uranus is the only sideways planet in the solar system, tilted a full 98 degrees and featuring a prominent polar cap. The extreme tilt places the Sun directly over the poles in summer, making “Arctic” summers and winters last more than 42 years, with violent storms during the transitions.

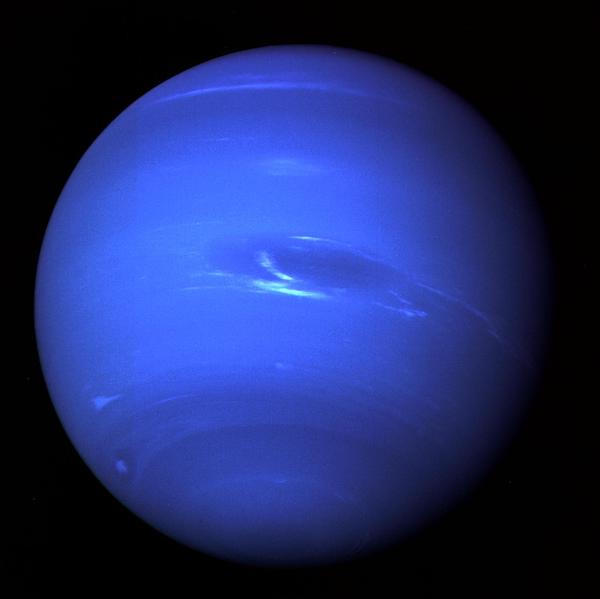

Neptune, on the other hand, features vast white, methane-ice cirrus clouds and mysterious dark storms, dubbed “dark spots.” Last year, one dark spot unexpectedly reversed direction, veering away from the equator where the vanishing Coriolis effect would have spelled its doom.

If a 1981 theory is right, Neptune may host the wildest weather in the solar system: diamond rains. Beneath its 1800-mile- (2,897-km-) thick hydrogen-helium atmosphere drifts a 10,000-mile- (16,093-km-) thick zone of methane ice. Atmospheric pressure one million times Earth’s and the planet’s own internal heat raise temperatures thousands of degrees. Scientists say that these extreme conditions can separate carbon atoms from hydrocarbons and squeeze them into diamonds that fall toward the core.

A team at Stanford University simulated such conditions with a specialized laser in 2017, and did succeed in producing tiny diamonds. Scientists believe this mechanism could explain why magnetic fields around Uranus and Neptune are asymmetric and not polar, emanating instead from a thin layer of metallic hydrogen formed as a by-product of diamond formation.

To discover whether this and other theories are correct, NASA is considering a mission to both planets in 2030 when the two will be favorably aligned. The journey will take ten years, crossing the orbits of worlds that host global sandstorms, supersonic jet streams, and methane floods. Weather permitting, it will be a wild ride through the solar system.