Key Takeaways:

Mars has dominated recent headlines as the newest generation of robotic explorers aims to uncover its secrets. But one day, robots won’t be the Red Planet’s only inhabitants. Human explorers will be next.

And whether we’re sending a small crew on a round trip or shuttling colonists with a one-way ticket, someday, somehow, someone will die on Mars. And because of the potentially prohibitive logistics and cost of transporting their body back home, it might very well need to stay there.

So, what would happen to a dead body on Mars?

How decomposition works

Humans evolved on Earth and our home planet is the perfect environment for us, alive or dead. On Earth, human remains eventually decompose as the environment recycles the body’s biomass, the organic material that makes us up. “Certain organisms basically have evolved to exploit the biomass of dead organisms. That’s just their thing, their niche,” says Nicholas Passalacqua, program director of the forensic anthropology program at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, North Carolina.

Here’s what (basically) happens when a person dies and decomposes, according to Melissa Connor, a professor of forensic anthropology at Colorado Mesa University in Grand Junction, Colorado. Early on, the body cools (algor mortis) and the blood begins to pool due to gravity (livor mortis). Rigor mortis, or temporary stiffening of the muscles, sets in. Then, cells begin to break down as the body’s own enzymes destroy them — a process called autolysis. Then putrefaction occurs, as the bacteria that help us digest our food keep right on trucking along. It’s autolysis and putrefaction that cause things like discoloration and other skin changes, as well as bloating. Scavengers (such as insects, birds, or other animals) and later fungi also move in, taking care of the rest of the cleanup. Connor does note that “decomposition is a continuum in which these processes may overlap,” so this isn’t necessarily a strict step-by-step process.

On Earth, the main factor that affects decomposition is temperature, Passalacqua says. “Temperature is really an important factor for the things that metabolize — that eat — human tissues,” he says. “So when you think about insects as a primary kind of scavenger of human soft tissues, insect activity is really temperature dependent.”

Temperature is a factor for another reason as well. “Sublimation occurs in freezing environments — the frozen water escapes to gas without going through the liquid form,” Connor says, the same way wet clothes can still dry hanging outside in the winter. So, in freezing Earth environments where water sublimates and the cold stops processes such as autolysis, “sublimation desiccates remains and creates mummies,” she says.

The martian environment

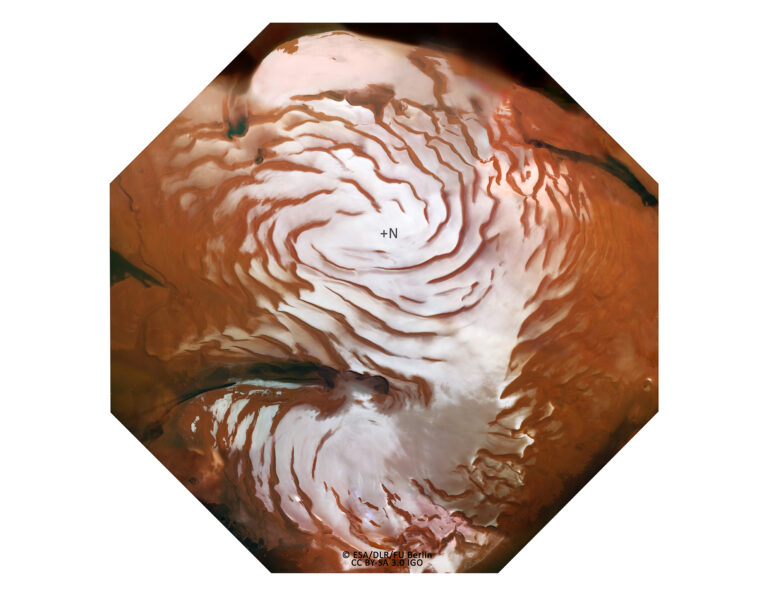

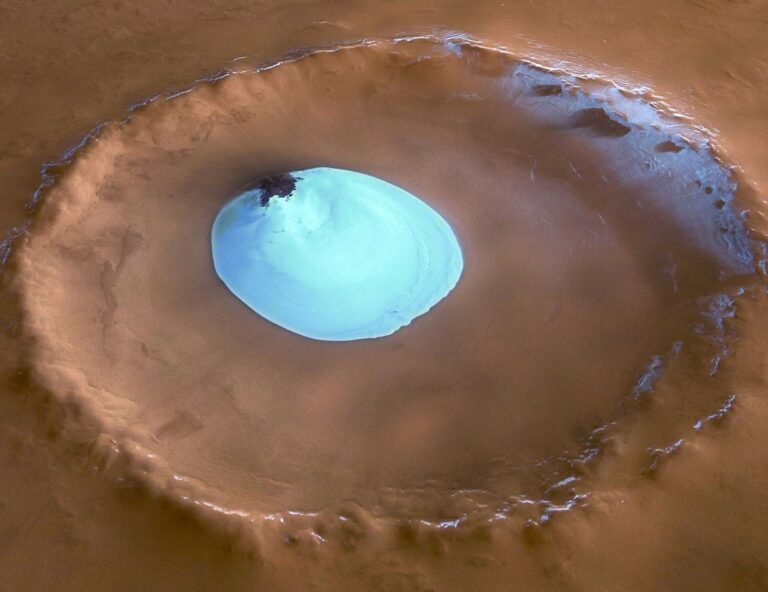

Although Mars may have looked more like Earth in the past, today it is a cold, dry planet with an exceedingly thin atmosphere composed of 95 percent carbon dioxide and only 0.16 percent oxygen.

Mars’ average temperature hovers around –81 degrees Fahrenheit (–63 degrees Celsius), but this can vary widely by location and season. For example, in October 2020, Mars InSight was reporting highs up to 24 F (–4 C) during the warmest part of the day and lows of –140 F (–96 C) at night.

And there is, of course, no liquid water and no known living organisms on the Red Planet’s surface today.

Mummies on Mars

All this is why Connor and Passalacqua agree: A body on Mars, if left outside or even buried in the loose martian soil, would probably dry out and mummify.

The first few stages — algor mortis, livor mortis, and rigor mortis — would still take place, Connor says. But there might be almost no other overt signs of decomposition, she adds. Autolysis and putrefaction would continue until the body froze, with one significant caveat: Most of the bacteria in our body are aerobic, meaning they need oxygen to function. On Mars, only the anaerobic bacteria that don’t require oxygen could proliferate until freezing, which means putrefaction would be severely limited.

After freezing, the body would dry out as its moisture sublimated away, leaving a well-preserved, natural mummy behind, the likes of which might have made the ancient Egyptians jealous. “The desiccated tissues would likely be very stable for an indefinite period,” Connor says.

“If you think about those peat bog bodies from the Medieval period, I would assume it would be kind of like that,” Passalacqua says. Those bodies — also remarkably well preserved — are mummified in part because peat bogs are oxygen-poor environments, which again limit the body’s own breakdown and prevent most organisms from coming in and finishing the job.

“If you think about a body going from something that looks like a person to something that looks like a skeleton, I don’t think you’re really going to get that in [the martian] environment. [Bodies] might dry out and mummify, but I don’t think much else would change,” Passalacqua says.

Dust to dust?

Exceptionally preserved martian mummies might sound like a cool idea. And the easiest and most straightforward option is, indeed, to bury the deceased. However, if human settlements on Mars really take off, cemeteries may require a bit of zoning planning and forethought, as the bodies in them would not decompose, preventing the reuse of plots.

Cremation, while a popular — and space-efficient — body disposal option on Earth, is probably not the best method on Mars. That’s because cremation requires keeping a chamber in excess of some 1,000 F (538 C) for several hours, which in turn requires immense energy input. In an environment where such fuel could be limited, that’s a costly solution. “That’s a huge amount of energy that’s just wasted to burn a body and not use for anything else,” Passalacqua speculates. After all, “you’re in this weird Mars environment, you probably want to be as economical as possible in all things.”

But both burial and cremation have a significant downside: the loss of potentially precious biomass. Remember that on Earth, decomposition is the ultimate recycling program, returning that biomass to the environment. “The environment that we’re in [on Earth] always wants to exploit [biomass] as much as possible. But the Mars environment’s not going to be able to exploit those resources at all, it’s just going to be lost resources for everybody,” Passalacqua notes.

In a place where bringing your own resources comes with high monetary and physical costs, is that really ideal?

Perhaps the best choice could be to recycle that biomass, as would occur on Earth. (It’s worth noting, of course, that processes like embalming largely halt decomposition, so all discussion of decomposition on Earth refers to non-embalmed remains.) In that case, it might be best to bury a body not outside in the martian soil, but instead it in a temperature- and moisture-controlled, Earth-like decomposition greenhouse with organisms such as insects and fungi to eventually turn that body into usable fertilizer or soil. Of course, those organisms would need alternative food sources when there are no bodies to consume, Passalacqua adds.

However, there is a scenario that could change all of this: With our aerobic bacteria unable to function, starved of oxygen in Mars’ atmosphere, our anaerobic bacteria could adapt to the martian environment — perhaps making it possible for bodies to decompose after all. “Evolution is ongoing and can happen quickly,” Connor says, noting, for example, the rapid appearance of COVID-19 variants throughout the pandemic. “And so I would not be surprised if something [that we carried from Earth] evolved quickly to take advantage of a new food source, particularly if there was a cemetery of colonists.”

Today, the only remains on Mars are those of defunct robotic missions, sparsely dotting the landscape as they gather layer after layer of rust-red dust. But when humans arrive, there’s clearly a lot we’ll need to plan for — including what to do with our dead.