Key Takeaways:

The longest-studied comets in our solar system have inspired ancient myths, religious fervor and modern scientific controversies. Now, the discovery of 88 asteroids and meteoroids orbitally aligned with one of them, Comet Encke, suggests that they all formed from the relatively recent breakup of an even bigger, icy comet. The findings are welcomed by those who believe Comet Encke and the other products of this astronomical event are responsible for many of Earth’s most violent and consequential impacts over the last 20,000 years.

Earlier evidence

Comet Encke was first observed in 1786 and later identified as the source of numerous annual meteor showers. Known collectively as the Taurids, these showers light up the skies of both the northern and southern hemispheres as Earth passes through a stream of debris created by the comet. (This year, look to the stars throughout November for a glimpse of your own.) In the 1980s, however, astronomer William Napier and astrophysicist Victor Clube suggested that objects larger than your average “shooting star” had arrived from a similar source as the comet.

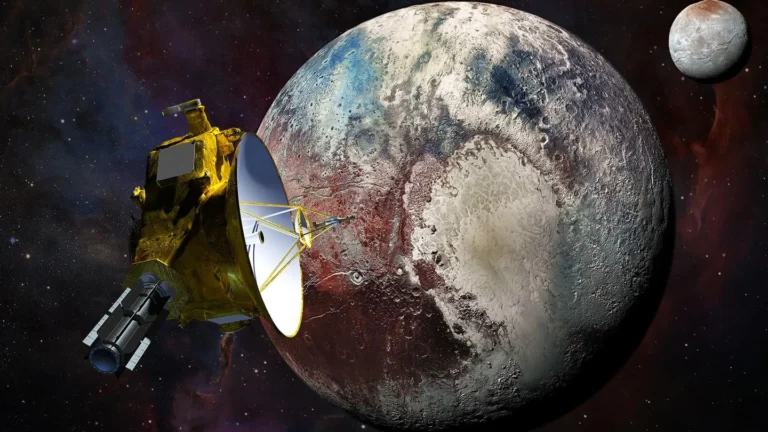

Early evidence came with the discovery of half a dozen asteroids, up to a mile across, orbiting inside the Taurid meteor stream. According to Napier and Clube, these rocky lumps — far too large to have been left behind by Comet Encke — could be explained by the fragmentation of some giant, 62-mile-wide comet 20,000 years ago. This is comparable in size to the recently discovered Bernardinelli-Bernstein “mega comet,” thought to be the largest in recorded history. In theory, this momentous breakup produced not just Comet Encke but an entire complex of asteroids, minor comets, pebbly debris and dust, which are today strung out in tightly bound concentric circles around the Sun.

Such a dynamic, unpredictable and well-populated complex capable of frequently getting close to Earth stoked academic imaginations; astronomers began to rewind the clock and look for evidence of Earth’s interactions with the Taurids in the archaeological record and beyond. Scientist Richard Firestone, now at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, in 2007 invoked the Taurid complex to explain global climate cooling at the start of a near-glacial period called the Younger Dryas and the sudden demise of the Clovis culture, a prehistoric people thought to be the ancestors of most indigenous peoples in the Americas. And last year, a team including Napier claimed to have found their own evidence of impact during the Younger Dryas: meltglass and scorched earth deposits that appeared to mark the demise of an early hunter-gatherer community in modern-day Syria.

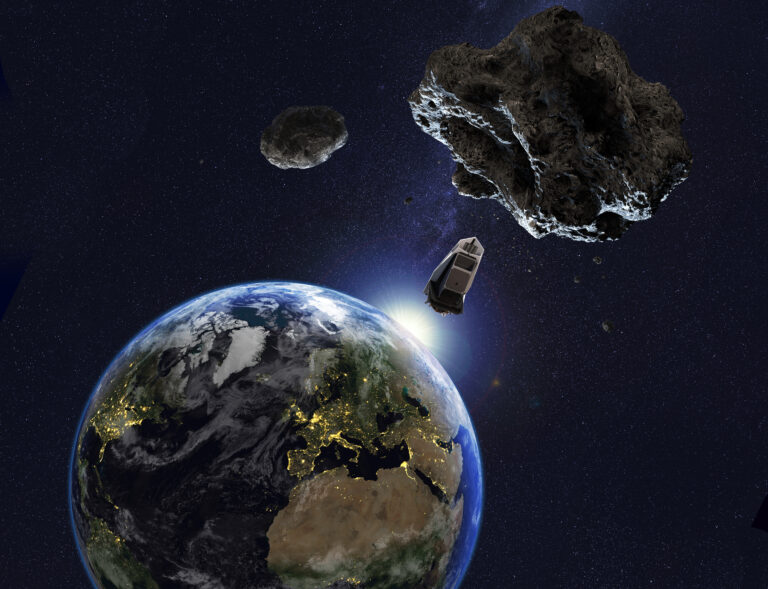

More recent close calls have also been linked to impactful events. In 1908, a small asteroid known as Tunguska entered the Earth’s atmosphere before exploding about five miles above an uninhabited part of Russia. Millions of trees were felled, devastating an area larger than 1200 square miles. Ignacio Ferrin, an astronomer at the University of Antioquia in Colombia, writes in his new book The Next Asteroid Impact that Comet Encke was at its minimum distance from Earth two weeks before Tunguska arrived. “That’s not a coincidence,” Ferrin says. “That implies that they are associated, in my opinion.”

Comet club membership

Now, Ferrin — who previously tracked down the Chelyabinsk meteor that injured more than 1500 people after breaking up in 2013 — has turned his attention to the Taurid complex itself. Together with Vincenzo Orofino from the University of Salento in Italy, he reanalyzed a dozen papers published in the decades since Napier and Clube’s original giant comet breakup hypothesis. Together, their orbital analysis of bodies increased the complex’s membership from half a dozen to 88. Additionally, using a technique called secular light curves, which looks for changes in each member’s brightness along its orbit, the researchers found evidence of cometary activity in 67 percent of the 51 new Taurid members they had good data on.

Most of the small bodies near Earth are expected to be long dead — stony worlds dislodged from the asteroid belt. While the orbital alignment of these 88 bodies with Comet Encke itself suggests that they share similar beginnings, Ferrin also sees the material that many of them appear to be releasing into space as a ‘smoking gun’ for a recently shared cometary origin.

Napier welcomes the findings. “Having asteroids in orbits resembling that of Comet Encke indicates either some unknown dynamical process, or that they are degassed fragments of a progenitor comet,” he says. “The finding by Ferrin and Orofino that a large proportion of the co-orbiting asteroids show signs of outgassing is evidence of the latter.”

What does this mean for our future encounters with the Taurids? David Asher, an astronomer at the Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland, says the latest work is “helping to build the picture of the original Taurid [forefather] presently having lots of debris in the inner planetary system.” Together with Kiyoshi Izumi from the Nippon Meteor Society in Japan, he has predicted two years in the next decade when we are likely to pass near the center of the complex: 2032 and 2036. (Mark your calendars.)

While Asher looks forward to a “noticeable enhancement of fireballs,” Ferrin is more concerned that the vaporizing and fragmenting Taurid asteroids might leave behind material too small for us to detect — but which could still pose danger if on a collision course with Earth. “The Tunguska cosmic body was 60 to 90 meters in diameter,” he says. “We now believe that the Taurid complex may contain many more objects of that size. It is not the tame, simple and innocent complex we thought it was.”