Key Takeaways:

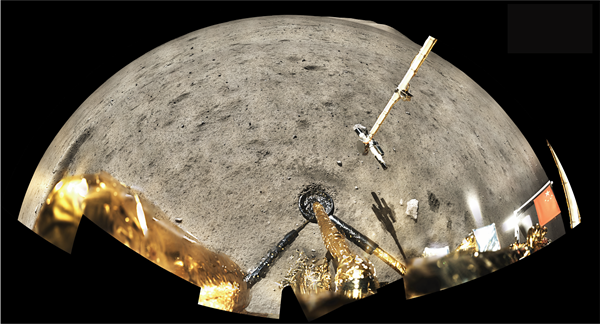

In December 2020, China’s Chang’e 5 mission touched down on Oceanus Procellarum — a region of the Moon that was once a vast plain of molten lava. The site had been targeted by scientists for decades: Curiously, its surface is somewhat sparse with impact craters, suggested that its last lava flood had occurred quite recently (in lunar terms). Determining its age was one of the mission’s top priorities.

In all, the Chang’e 5 lander scooped and drilled 3.8 pounds (1.7 kilograms) of lunar material, with its ascent stage delivering them to the grasslands of Inner Mongolia on Dec. 16, 2020 — the first Moon rocks returned to Earth since 1976. The stash was then collected and parceled out to several research groups. Now, nearly ten months later, scientists are beginning to report what they have found.

The first major scientific paper detailing mission findings was published today in Science. According to the team’s analysis, the samples confirm the relative youthfulness of the landing site’s volcanic rocks: 1.96 billion years old, give or take a few tens of millions of years. This is about a billion years younger than any of the volcanic lunar samples returned by the Apollo missions and the Soviet robotic Luna missions.

The find indicates that volcanoes were erupting on the Moon as recently as 2 billion years ago — which throws a wrench into our understanding of how bodies like planets and moons form. Scientists think that when such bodies are young, radioactive uranium and thorium sink deep into their interiors. These slowly decay and release heat, which, in a large body, can keep the mantle molten for billions of years. But models suggest that an object as small as the Moon should lose all its heat quickly.

“We always said that, OK, 3 billion-year-old basalts is fair enough, probably it can be sustained by this radioactive decay,” says Alexander Nemchin, a geochemist at Curtin University in Perth, Australia, and one of the team’s leaders. But 2 billion years is too young for current models, he says — “so now we’ve got a problem.”

Nevertheless, the result is exactly what scientists hoped for when they chose the probe’s landing site, says study co-author Brad Jolliff, a planetary scientist and mineralogist at Washington University in St. Louis. “This actually shows that the main science goal was met — and that’s pretty awesome.”

Dating the samples

The international team that conducted this study includes the Beijing SHRIMP Center. (A SHRIMP, or sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe, is an instrument used for chemical analysis.) “They have one of the best labs in the world,” says Jolliff. “It’s a really high quality lab, state-of-the-art using the best instrumentation.”

The team was allocated two grams of Chang’e 5’s lunar soil and picked out two tiny fragments that were basaltic rock, volcanic in origin. Then they analyzed various isotopes of lead, which are produced by the decay of radioactive uranium and thorium. Since these processes happen at a predictable rate, analyzing how much of each isotope exists, relative to each other, allowed the team to determine the age of the samples.

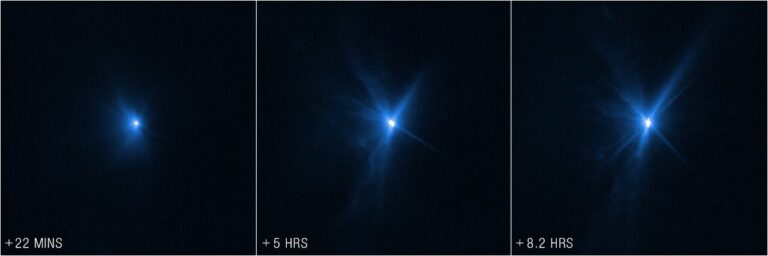

In addition to revealing the age of the landing site itself, the lead isotope measurements will help researchers improve a completely different technique for understanding the Moon’s history: counting impact craters.

Impacts were much more common in the solar system’s youth and eventually tailed off — but scientists don’t know exactly how quickly that happened. Measuring the age of the lunar surface and then counting how many craters appear in a given area of that surface allows researchers to calibrate a relationship that can be applied to other surfaces: The more craters it has, the older it is. “We know that kind of in a relative way, and we’ve known that for many years,” says Jolliff. “But to actually put numbers on that … required samples.”

To date, the most accurate measurements of the age of the lunar surface that exist were linked to rock samples 3 billion years or older from the Apollo missions and the Luna robotic missions. The Apollo samples also allowed researchers to infer some ages for some young impact craters that had formed within the past billion years.

“So we got the stuff less than a billion, and the stuff older than 3 billion,” says Jolliff. “[But] there’s this big gap of 2 billion years — from 1 to 3 billion years ago — that we had no actually calibrated surfaces. And so this result now gives us that age — and it’s right in the middle!”

The Chang’e 5 samples will now serve as a key data point in calibrating the crater chronology technique within that intermediate age range.

Rewriting lunar history

While this result is clarifying for the history of impact craters, our understanding of how magma could have been spewing from the Moon’s surface as recently as 2 billion years ago is murkier — there’s no clear source of heat.

The simplest explanation is that there were more radioactive minerals buried deep in the Moon than models predict. But the team says the lead isotope measurements give no indications that Chang’e 5’s samples originally contained any more uranium or thorium than samples from the regions visited by Apollo and Luna.

Perhaps buried radioactive material can still explain late volcanism if the minerals inside the Moon are different than scientists thought and can melt at lower temperatures, says Nemchin. But alternative explanations may be required.

One such hypothesis is tidal heating. Perhaps the tidal force of Earth’s gravity caused the Moon to stretch and deform, heating it and keeping it molten. When the Moon was younger, it orbited closer to the Earth, which would have enhanced this effect.

To test either scenario will require more analysis of the samples as well as detailed modeling. But one thing is certain, say researchers: The Chang’e 5 samples — and the prospect of more sample return missions in the near-future — are likely to ignite a new wave of interest in the Moon’s volcanism.

“When it’s just a suggestion, everybody tends to ignore it,” says Nemchin. “When you’re facing real data that confirm it, then that kind of forces you to go back and think.

“Yes, we suspected that younger basalts are on the Moon. But it wasn’t on the forefront of everybody’s thinking. Right now, it’s probably gonna be.”