Galaxies grow by attracting and absorbing smaller galaxies, beefing up their mass along the way. We have ample evidence our Milky Way has done exactly that, as well as a roadmap to how our galaxy will continue to bulk up in the future. We already know the Milky Way is surrounded by a plethora of smaller satellite galaxies that it will eventually devour. The largest of these is the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC). But now, researchers have shown that the galactic food chain extends even further: They have found evidence the LMC has likewise gobbled up its own share of small galaxies in its past, allowing it to grow into the sizable satellite we see today.

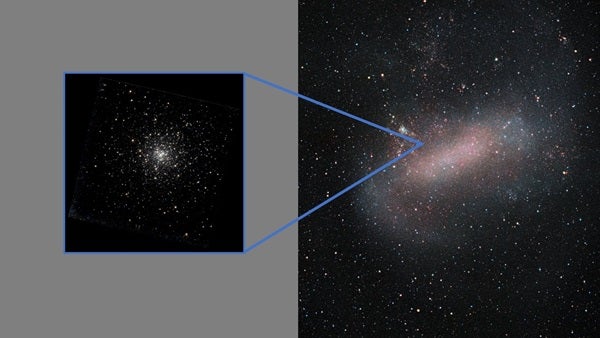

The evidence comes from one of the LMC’s globular clusters. These are ancient, compact groups of stars that, because they are so long-lived, can provide clues about a galaxy’s history. In this case, researchers studied 11 globular clusters in the LMC, comparing the mix of elements within their stars. One stood out: the cluster NGC 2005, which has fewer elements such as copper, calcium, silicon, and zinc than its brethren.

That elemental difference led researchers to surmise that NGC 2005 doesn’t have the same origin story as the other clusters. Instead, it’s likely all that’s left of a small galaxy the LMC gobbled up billions of years ago. Most of the unlucky galaxy was fully absorbed into the LMC, making it indistinguishable from the LMC’s own stars. But the central region of the galactic snack survived in the form of a globular cluster. The find, the team says, convincingly shows that even small galaxies can prey on each other to grow, more fully completing our picture of hierarchical galaxy evolution.

The work was published October 18 in Nature Astronomy.