Key Takeaways:

- The study analyzed 23 "polluted" white dwarfs, whose atmospheres contain elements from ingested planetary bodies, within 650 light-years of Earth.

- The composition of the pollutants in these white dwarfs revealed materials significantly different from those found in our solar system's inner planets and other known exoplanets.

- Researchers identified novel rock types in the white dwarf atmospheres, some with potentially lower melting points and different crustal thicknesses compared to Earth rocks.

- The observed differences in planetary compositions suggest a potential spatial variation in the galactic distribution of Earth-like planets, implying a possible element of chance in Earth's composition.

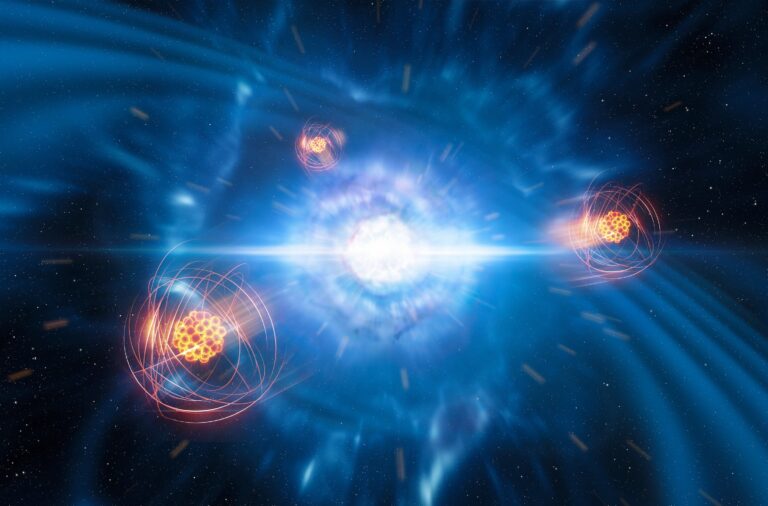

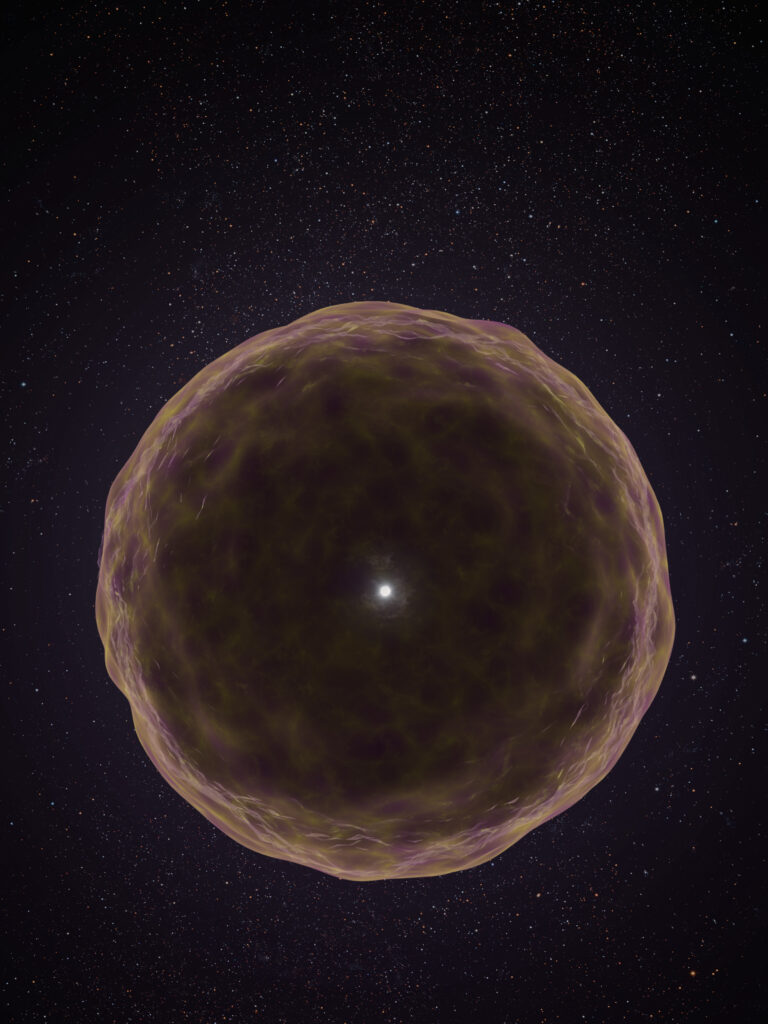

Debris from a former rocky planet spirals into a white dwarf in this artist’s concept. By looking at the atmospheres of white dwarfs that have swallowed bodies in their system, researchers have expanded our understanding of the compositions of exoplanets.

With over 4,000 exoplanets identified within our galaxy alone, it can be tempting to imagine that at least a few resemble Earth. But in truth, scientists have a difficult time figuring out what these bodies are made of — and thus whether they mirror our own planet’s composition.

To tackle the quandary, astronomer Siyi Xu of the NSF’s NOIRlab and geologist Keith Putrika of California State University looked not at exoplanets themselves, but instead at the dead stars that gobbled them up. And dealing another blow for the habitable worlds hunt, Earth-like objects were not at the top of the menu for white dwarfs.

Polluted white dwarfs

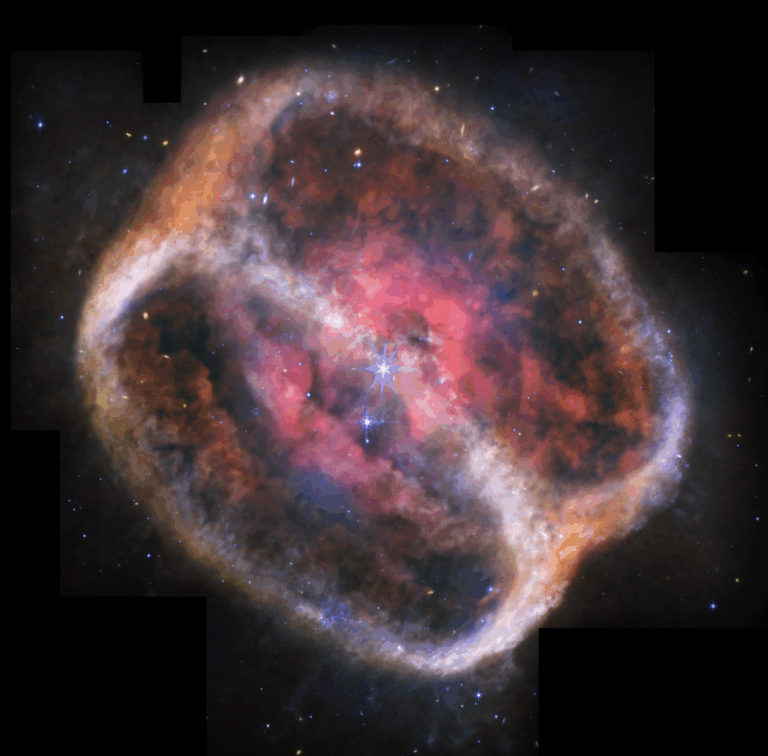

Stars exist thanks to a balancing act between the inward crush of their gravity and the outward pressure from their internal nuclear fusion. When a regular star depletes most of the hydrogen fuel in its core, the outward pressure drops and it begins to tip toward collapse. But such a star can get a second wind during its red giant phase, when fusion moves out from the core, making the star’s core contract and its outer shells expand. This increases the star’s temperature enough that it is able to fuse helium into carbon.

After this phase, stars like the Sun can’t get hot enough to “burn” carbon or oxygen. Instead, they completely blow off their outer layers, leaving behind a dense core composed of carbon and oxygen. A thin envelope of helium and hydrogen usually remains, hugging the surface of the stellar cinder. This atmosphere is only a few hundred meters above the surface — so transposing it on Earth would place it below the tops of skyscrapers.

This thin atmosphere is the key to the new study: Because these white dwarf atmospheres are only composed of hydrogen and helium, any other material seen must have come from foreign bodies — such as planets or asteroids. The study, published Nov. 2 in Nature Communications, looked at 23 so-called polluted white dwarfs within 650 light-years of our system and reconstructed the specific pollutants. The results weren’t just out of this world, they were out of this galaxy.

Strange rocks

Xu and Putrika found that the white dwarfs were polluted with material much more exotic than we see within the inner planets of our own solar system — or even in the other 4,000 exoplanets identified in the Milky Way so far. In fact, the researchers even had to create a few new names to describe the rock types they saw.

“Some rock types might melt at much lower temperatures and produce thicker crust than Earth rocks,” said Putirka in a press release, “and some rock types might be weaker, which might facilitate the development of plate tectonics.”

The researchers even think one of the white dwarfs devoured an object with an Earth-like composition. But ultimately, the differences in observed rock types compared to anything seen in our own solar system drove the researchers to wonder if Earth-like objects truly are rare. And if they are, is there a reason that Earth seems so different than our exoplanetary neighbors?

Because of the natural variation in certain elements as one moves further from the galactic center, the researchers suggest in their paper that “some parts of the galaxy are more disposed to forming Earth-like planets than others.”

So, perhaps we’re just lucky?