Key Takeaways:

Mars has become quite the hot spot. China and the United States landed rovers in 2021, while the UAE became the first Arab country to put a probe in the planet’s orbit. NASA, the ESA, India, and Japan all have upcoming missions, and the coming decades are slated for ambitious attempts to retrieve samples and even put human boots in the soil.

But this isn’t the first time the red planet has drawn our attention. While the 20th century’s space race is historically associated with the moon, the United States and Soviet Union also launched a slate of Mars missions. The USSR was especially attracted to Mars, seeing it as an opportunity to score their own historic moments after the American success of Apollo 11. And on December 2, 1971, Mars 3 achieved orbit, then sent down a lander that became the first spacecraft to safely touch Mars.

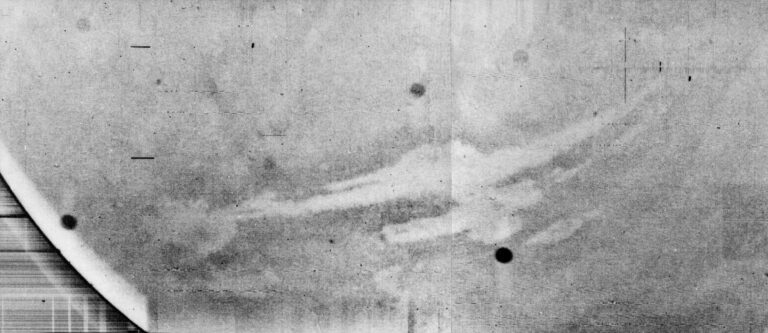

Mars 3 was meant to unleash a small rover, but contact was lost after just 110 seconds and only one grainy image was sent back. Showing what’s probably just radio static, the image was kept from the public until the days of glasnost, and news of the landing was largely overlooked in the west. But the technical achievement was part of a forgotten effort with its own glories and disappointments.

An underreported race

“The Soviet space program was under a lot of pressure in the 1960s to achieve ‘firsts,’” says Asif Siddiqi, a Fordham University history professor who’s penned multiple books on the Soviet side of the space race. “There had been interest in Mars in Soviet culture dating back to the early 20th century. A whole generation grew up learning about Mars through popular science fiction novels and movies, such as Sergei Korolev, who headed the Mars program in the early 1960s. So Mars was a natural objective. They even funded studies for human missions to Mars, although these were downgraded by the late 1960s.”

The Soviets began launching Martian probes in 1960, just three years after Sputnik 1. The vast majority failed to leave Earth, or even the launch pad, although 1963’s Mars 1, meant to fly by the planet and send back atmospheric data, was well on its way before contact was lost.

By 1971 the USSR had switched to the more powerful and reliable Proton-K rocket, and Mars 2 and 3 were launched. On November 14, America’s Mariner 9 became the first spacecraft to orbit another planet, beating Mars 2 by just 13 days. When Mars 2 joined Mariner 9 in orbit, it sent down its own lander, but it failed to deploy its parachute and crashed. That left Mars 3 to arrive and achieve the successful landing during a veritable Martian rush hour.

“The Soviets tried to get two spacecraft into Mars orbit in 1969, but in both cases the launch vehicle failed,” says Siddiqi. “My sense is that they were happy to get a couple of spacecraft to Mars but disappointed by the results of the Mars 3 landing. So close but so far!”

While the New York Times reported on the landing, the mixed result relegated Mars 3 to the back of newspapers. Mariner 9 had won the marathon, and the Soviets themselves had already been the first to land on another planet with their Venus 7 probe the previous year. But, in a sign that competition was still fierce between the superpowers, the Times did warn that Mars 3 suggested the Soviets had a five-year lead in the race for Mars.

“I think Mars 3 was definitely reported in places like New Scientist and Spaceflight, which were specialized publications, but less so in [general papers],” says Siddiqi. “I don’t think the landing got much coverage for two reasons — the Soviets were pretty secretive about the mission while it was happening, and the lack of surface pictures robbed it of any kind of spectacle value.”

A forgotten legacy

While the Times claimed that its Soviet counterpart Pravda spent a week praising Mars 3 and the team behind it, both that mission and its contemporaries are obscure today.

“I think the public tends to have a short memory as far as space exploration is considered,” Siddiqi says. “Besides the Apollo missions, most people would be hard pressed to know anything about what happened in space history in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s. People have some vague idea that rovers landed on Mars in the ‘90s but earlier than that is all a blur. I think the Viking landings were big news in the 1970s, but the sensational nature of those missions is really a footnote now.”

Even Marspedia, a whole site dedicated to Martian exploration, doesn’t have much to say about Mars 3. But its orbiter continued to transmit atmospheric data for eight months, while the failure of the lander — probably knocked out by an intense dust storm that scientists on both sides of the Cold War were surprised to learn about — made the case for increased flexibility and durability in mission design. The Proton-K rocket would be used until 2012, fueling 310 Russian launches.

Siddiqi calls the early Soviet Mars missions “outstanding in terms of their elegant and inventive design, and incredibly ambitious in terms of their goals.” Highlighting the clever design of the rover that Mars 3 had hoped to unleash, he says, “They had some successful orbiters, one partially successful landing, and several outright failures. But given the technical level of electronics, communications, power, etc. in the 1960s, it’s amazing that they achieved even that. I count the successful landing of Mars 3 as one of the great technical achievements of the Soviet space program, unfortunately robbed of a complete success by an act of nature.”

The United States would make up that five-year gap the Times feared, successfully landing the significantly more sophisticated Viking 1 on July 20, 1976. The Soviets never roamed Mars — after several more missions failed, they turned their focus to their far more successful Venus program. But in 2013, thanks to international cooperation that would have been impossible during the Cold War, a community of amateur Russian astronomers pored through photos taken by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and spotted what they believe to be the lost Mars 3 lander.

In reflecting on the golden anniversary of Mars 3’s historic first, Siddiqi highlights the mission’s human element. “The engineers who designed the early Mars probes, including Gregory Babakin, B. N. Martynov, V. A. Asyushkin, V. G. Perminov, and A. S. Demikhin, were a really smart team of designers. These were all basically young guys, some right out of grad school, who were allowed to dream big. They deserve accolades for working within a system that wasn’t necessarily kind to leaps of innovation.”

In honor of 50 years of robotic Mars exploration, the sixth Starmus Festival — a mash-up of space science and music — will take place in Yerevan, Armenia, from Sept. 5-10, 2022. Be sure to check it out!