Key Takeaways:

Most stars in the galaxy are spaced pretty widely apart, with light-years between neighboring systems. But stars are all moving in space, meaning sometimes brief, close encounters can occur as one flies particularly close to another.

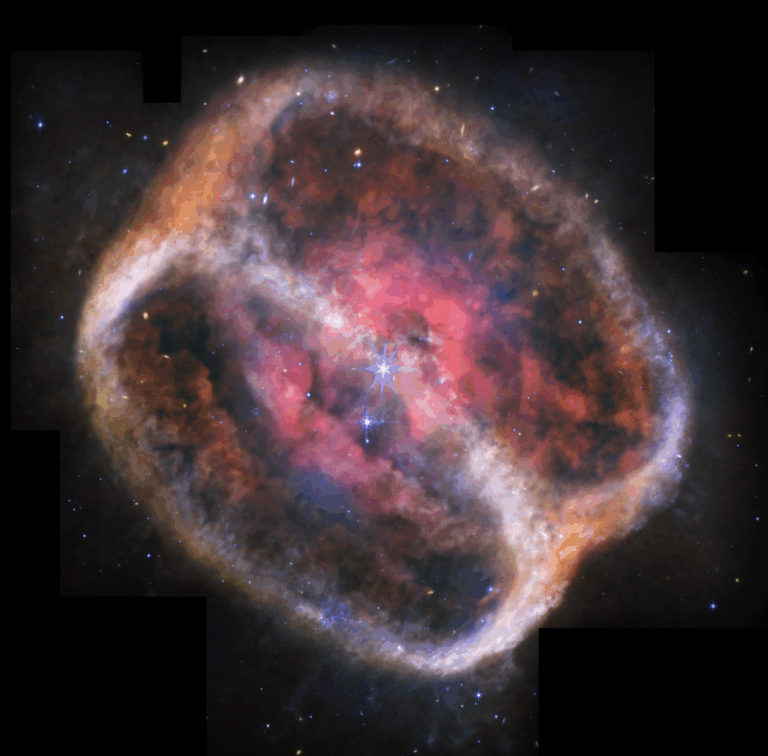

That’s just what astronomers believe took place in the Z Canis Majoris star system, which contains two extremely young stars. Because these stars are still forming, there’s still an appreciable disk of dust and gas surrounding them, which will ultimately either fall into the stars or create one or more planetary systems around them. And in new observations taken with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array and the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array, astronomers discovered that disk has clearly been upset. It even has long streams of material that has been tugged out of place.

By carefully determining exactly how the disk had been disturbed, the researchers ruled out normal, expected interactions between the two young stars. Instead, they can now confidently point the finger at a stellar “intruder” that recently flew past, disrupting the swirling material in the process.

Study leader Ruobing Dong of the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada, likened capturing the recent aftermath of such an event to “capturing lightning striking a tree.” Because flybys happen so quickly, cosmically speaking, it’s hard to find evidence of them because it’s washed away relatively quickly as well, as the disrupted material settles back down again. Although flybys have occasionally been detected in previous work, none have been captured in the same exquisite detail as this one. Now, the team hopes to use what they’re seeing — as well as future observations — to determine how such flybys could impact the evolution of both the stars and their future planetary system. That, in turn, could lead to better understanding the events — and chance encounters — that shaped our own solar system into the place it is today.