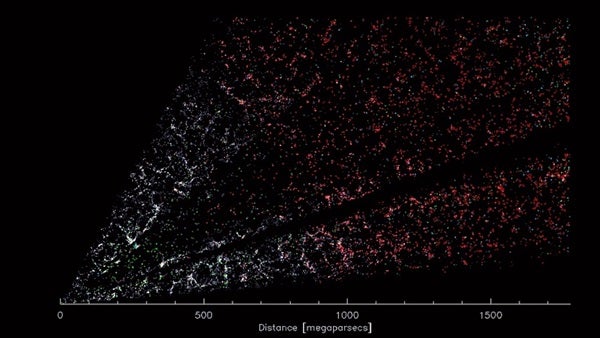

The universe is filled with galaxies — more than a trillion by some estimates — and we’ve only mapped a fraction of them. But answering some of the most pressing mysteries plaguing astronomers today, such as galaxy formation, dark energy, and the fate of the universe, requires a detailed 3D picture of how those galaxies are scattered through space.

Enter the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI). First conceived more than a decade ago, DESI is tasked with creating the largest 3D map of the cosmos to date, which will help scientists untangle the true nature of dark energy — the unknown force driving the expansion of the universe.

DESI, managed by Berkeley National Laboratory, is installed at the Kitt Peak National Observatory near Tucson, Arizona. The instrument saw first light in 2019, although its telescope was shut down shortly after due to the coronavirus pandemic, delaying the start of the science survey until May 2021.

Now, seven months later, DESI has smashed all previous records for 3D galaxy surveys — and it’s only 10 percent of the way through its five-year mission.

Mapping the universe

Creating a map of the cosmos isn’t as easy as hitchhiking around the universe and noting where things are located along the way. After all, we can’t travel to other galaxies — we’re stuck here in our own.

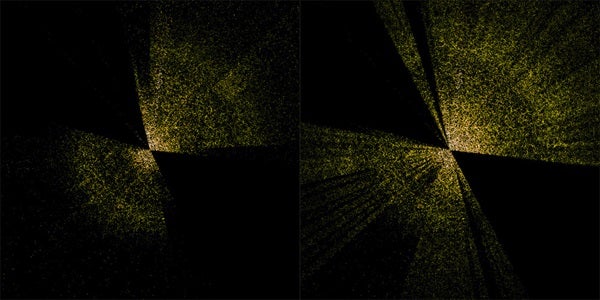

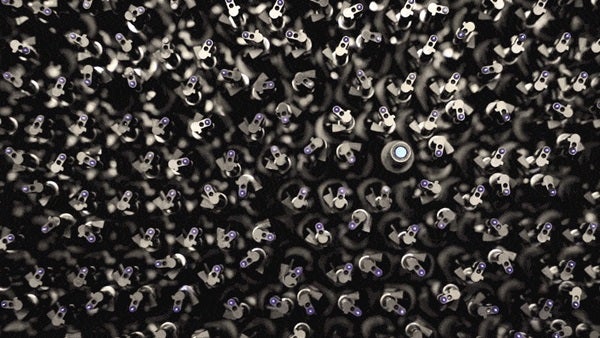

Instead, DESI is equipped with 5,000 fiber-optic “eyes”. Each eye is controlled by a single robotic positioner that points it to a specific spot on the sky, making it possible for DESI to target 5,000 galaxies every 20 minutes. Careful planning is needed to ensure none of these eyes bump into each other, but it only takes three minutes between sessions for all of them to reconfigure and focus in on a new set of galaxies.

But accomplishing this technical feat wasn’t the only hurdle that DESI had to overcome.

While the basic picture of the sky is visible to anyone who looks up at night, creating accurate maps is a bit trickier. Especially in 3D, because what we see when we look up is a 2D projection of the 3D cosmos. Before DESI could even get started, researchers needed to create a more detailed 2D map of the universe. What followed was a 6-year effort, stitching together more than 1 billion galaxy images taken from over 200,000 telescope images and years of satellite data. The new map comprises an astounding 1 petabyte of data — enough to store 1 million movies.

With that new 2D map in hand, DESI began to survey the sky on May 17, 2021.

Tackling the big question

The universe has been growing ever since it began. This expansion carries all matter, including galaxies, within the cosmos farther apart, like raisins embedded in a rising loaf of raisin bread. As they move farther away, the light reaching us from distant galaxies is stretched into longer and longer wavelengths. Generally, the more stretched, or redshifted, a galaxy’s light, the more distant the galaxy is.

By collecting detailed color images of galaxies, DESI can determine how much the light from each galaxy is redshifted. And this adds the third dimension — depth — to our picture of the universe.

By knowing the distances to galaxies and other bright objects, astronomers can paint a better picture of how the universe came to be the place we see today.

“There is a lot of beauty to it,” said Julien Guy, a Berkeley Lab scientist. “In the distribution of the galaxies in the 3D map, there are huge clusters, filaments, and voids. They’re the biggest structures in the universe. But within them, you find an imprint of the very early universe, and the history of its expansion since then.”

With its thousands of eyes, DESI can peer up to 11 billion years into the universe’s past. And ultimately, researchers are hoping that by shedding light onto the history of the universe, they’ll be able to better predict its future.

Since the 1990s, astronomers have known that our universe isn’t expanding at a constant rate. Instead, it is accelerating. The phenomenon has been attributed to a mysterious force known as dark energy. Dark energy makes up about 69 percent of the universe; dark matter accounts for another 26 percent and the visible, or normal, matter we’re familiar with is a measly 5 percent. But as the universe expands, more dark energy pops into existence, which drives the expansion of the universe on even faster. If this cycle continues, trillions of years from now, all but our nearest neighboring galaxies will be too far away to see. And eventually, the universe will end in what’s known as the Big Freeze.

By getting the full picture of how dark energy has behaved in the past, cosmologists will be able to tell whether the universe is really headed toward this chilling fate or if other models of its end are more likely.

In the meantime

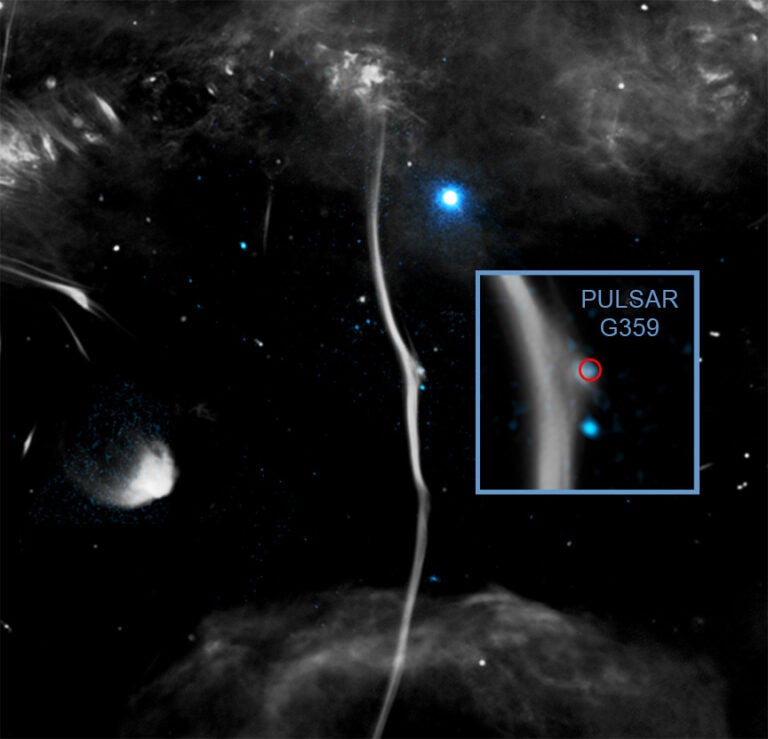

Answering the questions surrounding dark energy won’t occur until after DESI has finished its survey, however. In the interim, DESI is tackling a few more manageable questions, like black holes.

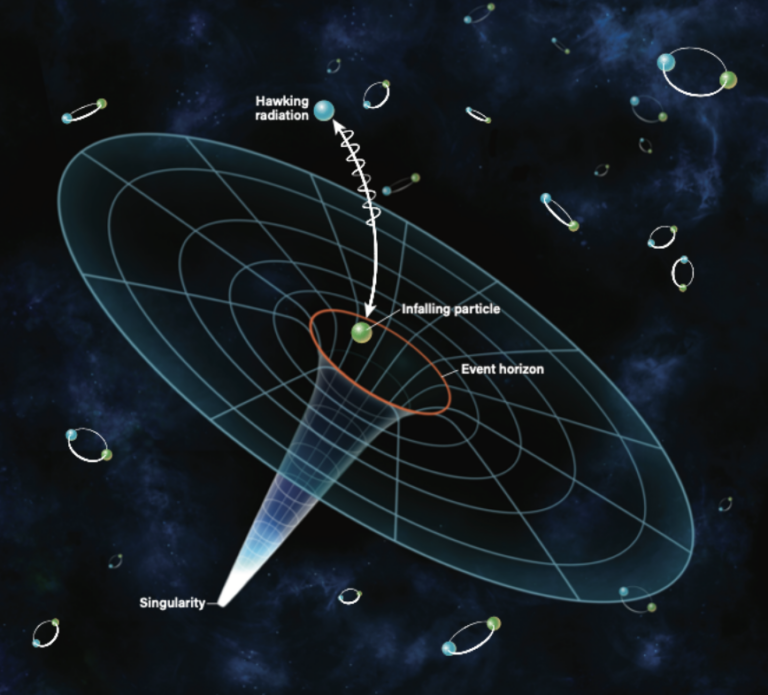

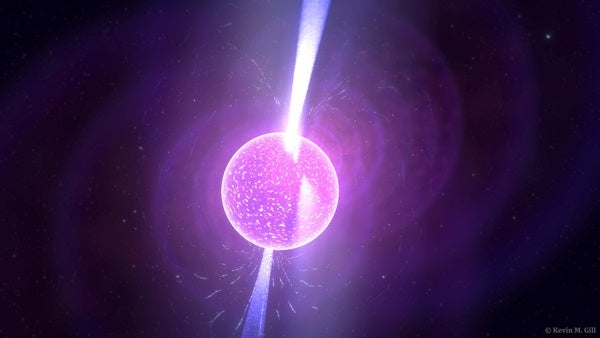

Black holes are regions in space where gravity is king — nothing, not even light, can escape them. Scientists suspect that supermassive black holes, millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun, lurk at the center of most galaxies. But researchers don’t fully understand how these monsters managed to get so big so quickly in the early universe.

Intermediate-mass black holes, weighing in at 100 to 1,000 solar masses, are one solution to that problem, bridging the evolution gap between stellar-mass black holes and supermassive black holes. But finding these black holes is tricky and only a handful of intermediate-mass black hole candidates have been identified to date. With DESI, researchers can look for low-mass galaxies that are most likely to host these intermediate-mass black holes.

Scientists can also use DESI to study some of the brightest objects in the universe: active galactic nuclei, sometimes called quasars. When matter falling into a supermassive black hole heats up, it radiates light before it disappears forever into the black hole. According to researcher Victoria Fawecett, these objects are like lampposts, allowing astronomers to peer through the darkness “back in time into the history of the universe.” And using DESI, astronomers are finding more and more of these objects and thus coming to better understand how they evolved.

With more than 7.5 million galaxies already cataloged and a million more being added every month, there’s no telling what other secrets DESI will uncover in the years to come.