Key Takeaways:

Strange strands

About 25,000 light-years from Earth, the 1-dimensional filaments were first discovered in the 1980s by Northwestern University’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences physics and astronomy professor Farhad Yusef-Zadeh, then a graduate student. At the time, Yusef-Zadeh identified only 100 strands but, with the help of technology, researchers have now pinpointed almost 10 times more and are one step closer to finding the objects’ origins.

According to a study published Feb. 2 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the strange strands are thought to be made of cosmic-ray electrons moving in a magnetic field at nearly the speed of light. They appear in equally spaced clusters or pairs covering an area of about 150 light-years. Yusef-Zadeh says the significance of the findings comes from the idea that most celestial bodies in the universe have a source of acceleration, such as black holes. However, these filaments are very high energy — and without a direct source.

Looking deeper

In the past three years, Yusef-Zadeh and other researchers worked with the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory’s MeerKAT telescope to map a large portion of these mysterious strings. The professor notes that using this facility was beneficial because the 64 telescopes spent over 200 hours viewing the objects.

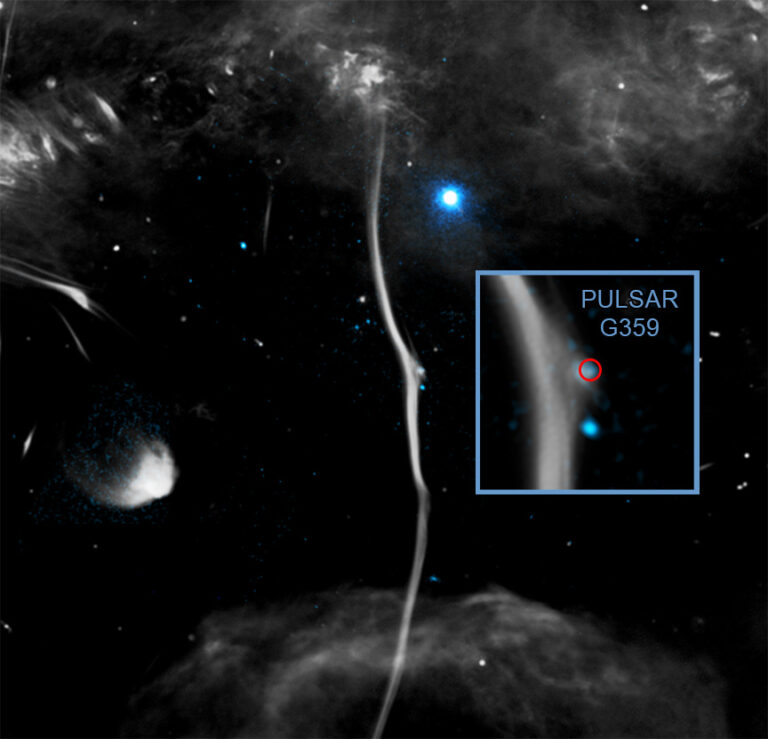

The team then created a mosaic image of the filaments by putting together 20 different images taken over those three years. Yusef-Zadeh says it was challenging to combine so many datasets into one cohesive piece.

“It was a huge amount of data with lots of different fields. It can be quite complicated and time consuming to align all the different fields,” he says. “A lot of credit goes to Ian Heywood.”

Heywood, an astrophysicist at Oxford University, will soon publish a paper — co-authored by Yusef-Zadeh — using the data from the MeerKAT. He helped to compose the image as well as captured the radio transmissions of other stars and celestial bodies in the meantime.

“I’ve spent a lot of time looking at this image in the process of working on it, and I never get tired of it,” Heywood said in a press release. “When I show this image to people who might be new to radio astronomy, or otherwise unfamiliar with it, I always try to emphasize that radio imaging hasn’t always been this way, and what a leap forward MeerKAT really is in terms of its capabilities. It’s been a true privilege to work over the years with colleagues from SARAO who built this fantastic telescope.”

To create the clearest picture, researchers isolated the strands in the images to eliminate other background objects. To do that, they borrowed an algorithm from astronomers taking images of solar loops. Yusef-Zadeh says the strands in the center of the galaxy shared characteristics with the narrow structures we see “bursting and pulling” off the surface of stars.

Mysteries remain

Although researchers are now able to visualize these objects, knowing where they came from is a bit more complicated. Yusef-Zadeh says there are two possible candidates to explain the phenomenon. He explained that Milky Way’s center is turbulent and chaotic, which may create self-generated strands. The other possibility is that they are generated by a compact source that has yet to be identified.

Later this year, Yusef-Zadeh hopes to publish another paper detailing the filaments’ individual length distribution, separation, curves, and magnetism, among other characteristics. The findings could lead to a better understanding of why these objects look the way they do.