It’s been a mixed few months for SpaceX’s Starlink constellation. The company continues to ramp up deployments of the internet service-providing satellites, which with today’s launch, will push the number in orbit close to 2,000. But the company has also drawn increasing scrutiny, with both China and NASA recently raising concerns about Starlink’s potential to cause collisions with other objects in low-Earth orbit.

Now, SpaceX is seeking to assuage some of these concerns. In a statement posted on its website Feb. 22, SpaceX pledged it is “committed to maintaining a safe orbital environment, protecting human spaceflight, and ensuring the environment is kept sustainable for future missions to Earth orbit and beyond.” The company argued that it has designed Starlink to be a safe and sustainable system and revealed details about how its satellites act autonomously to avoid collisions — details that it had previously only hinted at, or that analysts had suspected.

“This is certainly the most detailed explanation SpaceX have given of their procedures,” Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told Astronomy. “It is welcome, although a couple years later than it could have been.”

Collision course

Astronomers and dark sky advocates have long raised concerns about Starlink, which seeks to provide broadband internet access to anywhere in the world. The satellites leave bright trails through astronomical images and are especially visible to the naked eye shortly after they are launched, before they ascend to their operational orbit.

However, SpaceX’s statement comes as concerns about collisions are getting more attention. On Dec. 3 of last year, in a rare move, China submitted a complaint to the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, saying that the nation’s crewed space station had to perform a maneuver to avoid a potential collision with a Starlink satellite on two separate occasions, July 1 and Oct. 21 of last year. (McDowell verified the orbital maneuvers with public tracking data.)

In a Dec. 28 press briefing, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman accused the U.S. of ignoring its obligations under the Outer Space Treaty, Bloomberg reported. That treaty holds that nations that have signed it bear the responsibility for supervising their country’s activities in space, whether done by a national space agency or a commercial operator.

Then, on Feb. 7, NASA’s human spaceflight division submitted a letter to the Federal Communications Commission raising concerns about Starlink’s plan for its second-generation constellation, for which SpaceX is seeking approval to launch 30,000 more satellites. In the letter, which was first reported by Space News, NASA said a megaconstellation of that size would raise the risk of collisions in space that could threaten its satellites and astronauts. The agency also said that glints of reflected sunlight could interfere with its space telescopes and Earth-observing satellites.

Low flyers

SpaceX says one way it prevents Starlink satellites from becoming defunct obstacles in space is by launching them to very low orbits to do their initial system checks, just 130 miles (210 kilometers) high. By comparison, the International Space Station and China’s Tiangong station orbit around 250 miles (400 km).

At 130 miles, spacecraft experience significant drag from stray air molecules and will lose momentum and reenter the Earth’s atmosphere within days. That way, if a satellite fails to come online and is unable to fire its thrusters to boost itself to a higher orbit, it quickly falls out of space.

SpaceX experienced one risk of this strategy Feb. 3 when it launched a batch of 49 Starlink satellites into the middle of a solar storm. Flares from the Sun enhanced activity in Earth’s magnetic field, warming the atmosphere and causing it to expand outward. SpaceX said the Starlink craft experienced an atmospheric drag force that was up to 50 percent stronger than usual. As a result, 38 of the 49 satellites fell out of orbit and were destroyed, potentially costing the company tens of millions of dollars. “Despite such challenges, SpaceX firmly believes that a low insertion altitude is key for ensuring responsible space operations,” it said in Tuesday’s statement. (For its next Starlink launch Feb. 21, it used a slightly higher orbit.)

SpaceX also reiterated in its statement that it has chosen 550 kilometers (342 miles) as the operational altitude for Starlink craft — and not any higher — because at that altitude, spacecraft will naturally reenter the atmosphere due to drag within a few years. By contrast, a Starlink satellite at 750 kilometers (466 miles) would take about half a century to reenter.

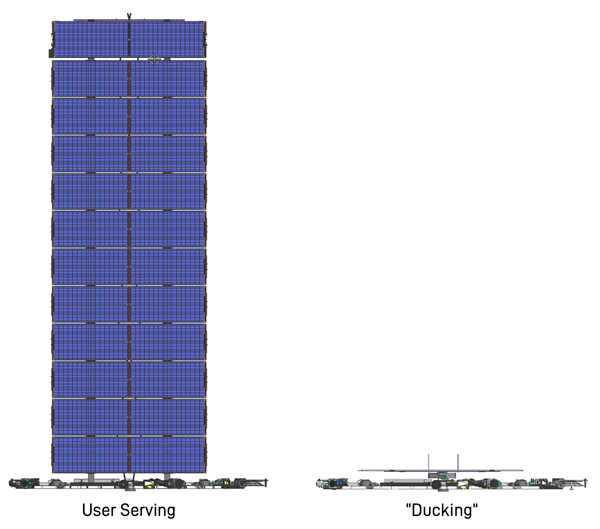

Duck and move over

SpaceX also shed light on how Starlink satellites autonomously avoid collisions — a capability it has previously touted but offered few details about. This became a point of speculation after China’s complaint. McDowell noted that in one of the two incidents where China moved its space station, the Starlink satellite appeared to have also taken avoiding action; in the other, the Starlink satellite did not change course. It was unclear whether SpaceX would have notified China’s space agency about the maneuver, raising the possibility that both craft could inadvertently maneuver closer to each other.

On Tuesday, SpaceX said that if public tracking data shows a Starlink satellite has a 1 in 100,000 chance of a collision with another craft, it automatically “assumes maneuver responsibility” and autonomously takes avoiding action. If the other satellite is operated by a different organization, the Starlink satellite always maneuvers to avoid — it never leaves it up to the other craft. If data indicates a “high-probability conjunction with another maneuverable satellite,” SpaceX says it coordinates any maneuvers with that satellite’s operator.

SpaceX also said that Starlink satellites can “duck” as they pass by another object by lowering their shark-fin solar panels so that they face the oncoming craft edge-on, reducing its profile and the chance of a collision by a factor of four to ten.

McDowell says that he is happy to see SpaceX disclose more of its operational practices, but that the company could still be “a lot less vague” on some details — for instance, what exactly the 1-in-100,000 threshold translates to in terms of distance in practice, and exactly how much of a berth Starlink satellites give the ISS and Chinese space station.