NASA is currently aligning the 18 gold-coated mirrors on the $10 billion James Webb space telescope (JWST), the world’s largest and most powerful technology of its kind. JWST was launched this past Christmas and will soon open a whole new chapter in space research: The telescope will help scientists examine the most distant planets in detail and investigate the dawn of the universe.

It took a massive undertaking to deliver JWST, which weighs over 7 tons, to its current spot a million miles from Earth. Only the Ariane 5 rocket is powerful enough to lift such a heavy load — but even Ariane is not big enough to contain it. So the huge telescope had to be folded up to fit in, thus making a very complicated telescope even more so.

A long journey to launch

Before the launch could even occur, JWST had to be packed into a huge protective container called STTARS (Space Telescope Transporter for Air, Road and Sea). STTARS weighs 168,00 pounds and measures 110 feet long and 18 feet high. A heating, ventilation and air conditioning system controls the temperature and humidity inside the container and trailers accompany it with pressurized bottles to supply clean, dry air.

The trip from JWST’s California birthplace to the launch site began on the road. The precious cargo approached the port of Naval Weapons Station Seal Beach at 5 or 10 miles per hour. Before setting off, the NASA team used satellite imagery to check route surveys, potholes that needed to be filled, and traffic lights that had to be lifted. “There are just thousands of different things that go on behind the scenes: pulling permits, avoiding obstructions, selecting alternate routes … all kinds of nuances,” Charlie Diaz, the launch site operations manager, told the agency.

At the Naval Weapons Station, STTARS was loaded onto a cargo transport ship that set sail for French Guiana, a country on the north Atlantic coast of South America that is home to the European Space Agency’s Primary Launch site. This 5,800-mile sea voyage brought the telescope through the Panama Canal to Port de Pariacabo in French Guiana, then by road to the launch site.

When go time finally arrived, the launch proved nerve-wracking. “The Ariane 5 rocket is very reliable but no rocket is 100 percent perfect so there’s always that nervousness when you see 20-plus years of planning, building and development on top of basically what is a giant firework,” Martin Barstow, a professor of astrophysics and space science at England’s University of Leicester, told reporters.

Blasting off

At 7:25 a.m. EST on Christmas Day, the Ariane was launched “from a tropical rainforest to the edge of time itself” as one commentator said. Two minutes later, the rocket was traveling at almost 5,000 miles per hour. After the fuel ran out, sections of the rocket were jettisoned into the Atlantic Ocean. When the Ariane was 80 miles above the Earth’s surface and therefore outside our atmosphere, the nose cone was no longer required to make it aerodynamic. This piece was separated into two halves and jettisoned to save weight.

Twenty-five minutes into the flight, the only remaining part of the Ariane rocket — the small upper stage engine — took over the job of carrying the JWST and burned one ton of fuel per minute for 15 minutes in order to ramp up the speed to 21,400 mph. The JWST then separated from the upper engine and began its solo journey.

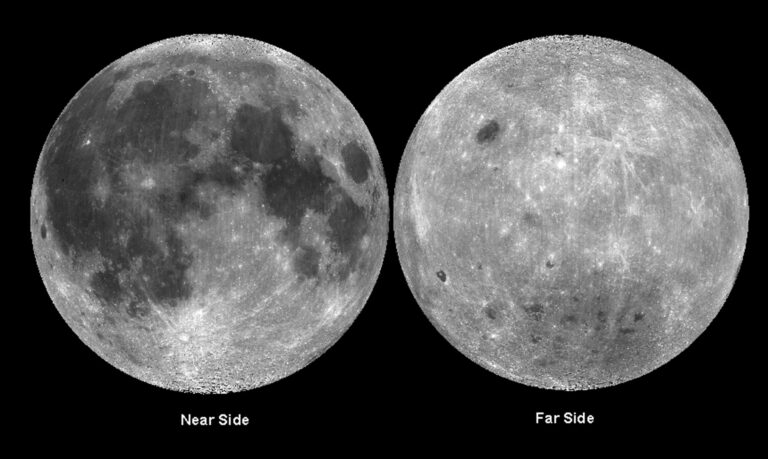

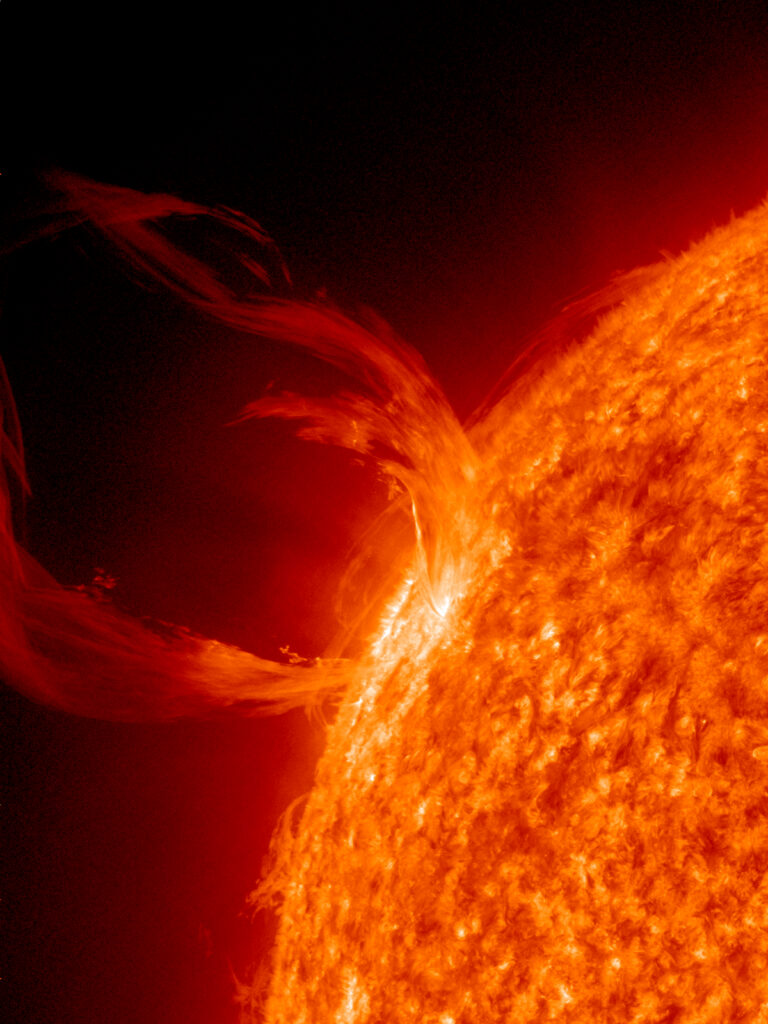

After much anticipation, the JWST reached its final position and synchronized with the Earth’s orbit around the sun. In this spot, the combined gravitational pull from the sun and Earth will keep the telescope from careening into space. There are many advantages to this location; for one, it’s far enough from us to provide a clear view of the universe, but close enough to readily communicate with Earth. To avoid heat and light from sources like the sun, Earth and moon, the tennis court-sized sunshield will provide the telescope with five layers of protection and keep it at a cool, steady temperature (sort of like an umbrella).

After a perfect ride into orbit, the world watched as JWST reached its observation post with a superb view of the Universe. At the time, NASA’s chief administrator Bill Nelson said, “This is a great day not only for American, European and Canadian partners but it’s a great day for planet Earth.”