The Hubble Space Telescope has imaged the most distant star ever seen, according to a study published today (March 30) in the journal Nature. Astronomers identified the supersized star — which almost certainly died in a fiery explosion nearly 13 billion years ago — thanks to a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing.

“It took this wonderful cosmic coincidence,” said astronomer Michelle Thaller of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “Everything was lined up perfectly. A nearby cluster of galaxies was lensing space, actually bending space into this natural telescope.”

Such gravitational lenses are not always so powerful, said Brain Welch, a PhD candidate at the Johns Hopkins University who led the study. “Typically, you know, if you have a lensed galaxy, it would be magnified by a factor of a few to perhaps ten.” But here, the configuration was just right, leading to an individual star at the edge of the lensed galaxy being magnified by a factor of thousands.

In this case,” said Welch, “we just got really lucky with the alignment.”

Earendel: Meet the morning star

The newfound but long-dead star is officially designated WHL0137-LS. However, the researchers have given the ancient beacon the nickname “Earendel,” which is an Old English word meaning “morning star” or “rising light.”

Just a few years ago, Hubble glimpsed another extremely far-off star named Icarus, which shone when the universe was some 9.5 billion years old, or 30 percent its current age. However, Earendel smashes the record Icarus once held. Earendel lived roughly 12.9 billion years ago, when the universe was just 6 percent its current age.

“When the light that we see from Earendel was emitted, the universe was less than a billion years old,” said co-author Victoria Strait, a postdoc at the Cosmic Dawn Center in Copenhagen, in a press release. “At that time, it was 4 billion light-years away from the proto-Milky Way, but during the almost 13 billion years it took the light to reach us, the universe has expanded so that it is now a staggering 28 billion light-years away.“

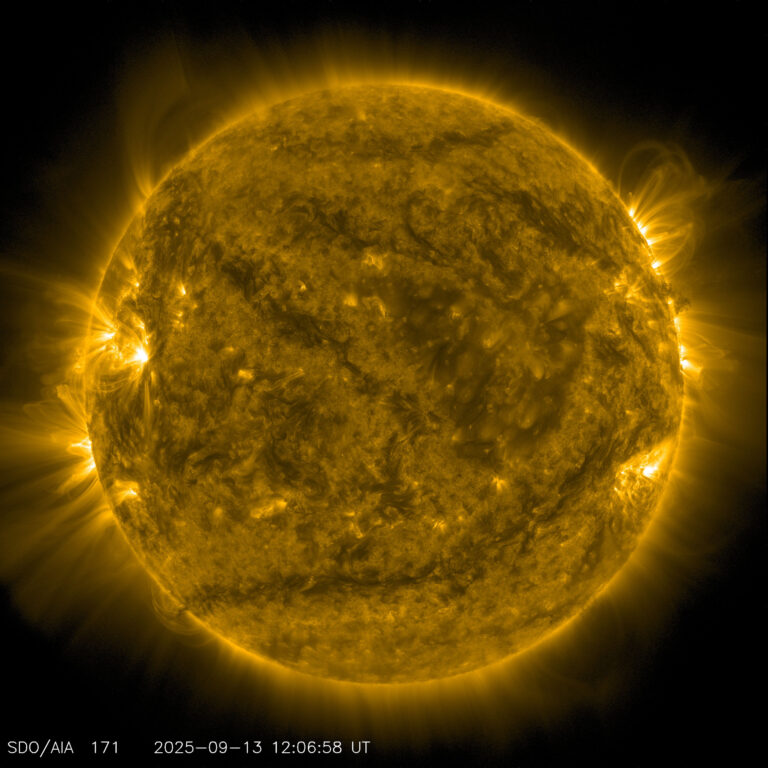

Earendel shines millions of times as brightly as the Sun and might have weighed as much as 500 solar masses. But the researchers think it was more likely between about 50 and 100 solar masses. “Stars like that don’t live a long time,” said Thaller. “So, we’re seeing light from a star that probably itself only lived a couple of million years. It blew up long, long ago.”

“So, it’s kind of this wonderful gift from the universe,” added Thaller. “A chance to look back in time. A chance to learn more about where we came from, what things were like around here billions and billions of years ago.”

Moving forward, Hubble senior project scientist Jennifer Wiseman is hopeful that “as we study it more, [we’ll] learn about how it was formed, what it’s made of, and start understanding how the earliest stars in the universe contributed to their galaxies and to subsequent generations of stars like our own Sun.”

“Studying Earendel will be a window into an era of the universe that we are unfamiliar with, but that led to everything we do know,” said Welch in a press release. “It’s like we’ve been reading a really interesting book, but we started with the second chapter, and now we will have a chance to see how it all got started.”