Key Takeaways:

Light from space always reaches us after a delay. For example, the light from our nearest star system, Alpha Centauri, takes four years to reach Earth, so when we look at Alpha Centauri, we see it as it was four years ago.

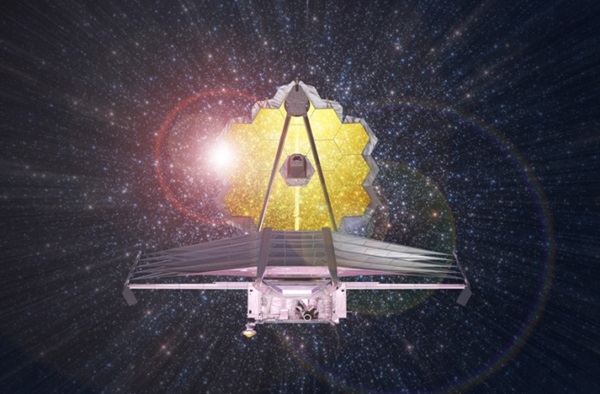

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will take this idea to the extreme, studying objects so distant that the telescope will essentially be looking back 13.5 billion years — close to the start of the universe.

Early light

The Big Bang occurred 13.8 billion years ago. One second afterward, the universe consisted of radiation, hydrogen, helium and high energy particles at a temperature of 18 billion degrees Fahrenheit. Around 400,000 years later, the temperature had cooled to 5,500 degrees Fahrenheit and the universe was glowing dull red. As the universe continued to expand and cool, that glow disappeared and the universe became completely dark, the so-called Dark Ages.

The particles from the Big Bang grouped together due to gravity and formed the first atoms. Those atoms grouped together in clumps, eventually becoming stars. When the first stars formed they also began to emit the first light, which JWST was built to detect.

The Hubble telescope can also look back in time to a certain extent, but not as far as JWST does. Hubble has been orbiting Earth and giving us both amazing images of the universe and important scientific results for more than 30 years, but its mirror is only 8 feet in diameter, which limits its ability to observe the most distant objects. What’s more, light from the most distant objects is stretched due to the expansion of the universe, becoming infrared wavelengths, which Hubble cannot easily detect.

By comparison, JWST is designed to collect infrared radiation, thanks to its much larger 21-foot diameter mirror. There are other benefits in collecting infrared radiation besides viewing faraway objects. Stars and planets that are just forming are surrounded by dust, which absorbs visible light; however, infrared radiation can penetrate that dust. Thus, JWST can see both farther and fainter objects than Hubble ever could.

Back to the beginning

To do that deep stargazing, JWST must look at one patch of the universe for a long time in order to collect as much light as possible from the distant objects astronomers seek to view. “We are trying to build up the story of how the first galaxies ever emerged and how those evolved into galaxies we see today and we live in today,” said Marusa Bradac, an astronomer at the University of California, Davis, in an interview with NPR. “If you don’t get the beginning right, it’s really difficult to figure out what the whole evolution looked like”.

Unlike Hubble, JWST will be able to see right into stellar nurseries, where stars and their planetary systems are born. The observations will answer questions about how clouds of dust and gas collapsed to form stars and how the planetary systems formed around them.

A further goal for JWST is to try to understand the formation of the elements. After the Big Bang, the very high temperature and density produced the simplest elements, mostly helium and hydrogen. We know that all the other elements — carbon, gold, silicon and more — were created in nuclear reactions in the stars and in the huge stellar explosions we call supernovas, which scattered the elements into the galaxy. But we don’t entirely understand the processes involved.

Seeing further

Astronomers from around the world will be able to apply for time using JWST to support their research and much of the new research will be the study of exoplanets. Twenty years ago, no other planets were known apart from those in our solar system. Since then thousands of planets, the exoplanets, have been discovered in orbit around stars. The plan is for JWST to study the atmospheres of the exoplanets to determine whether they could support life — or the telescope might even detect the presence of life itself.

“The James Webb Space Telescope represents the ambition that NASA and our partners maintain to propel us forward into the future,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson in a NASA news release. “The promise of Webb is not what we know we will discover; it’s what we don’t yet understand or can’t yet fathom about our universe …. We are poised on the edge of a truly exciting time of discovery, of things we’ve never before seen or imagined.”