When it comes to spring cleaning, you might want some help from a dwarf galaxy.

Using a new atlas of star-forming galaxies, astronomers found smaller star-forming galaxies are much more efficient at expelling gas and dust than their larger counterparts. The findings, submitted to the Astrophysical Journal and published today on the preprint server arXiv, are helping astronomers better understand how galaxies grow and evolve.

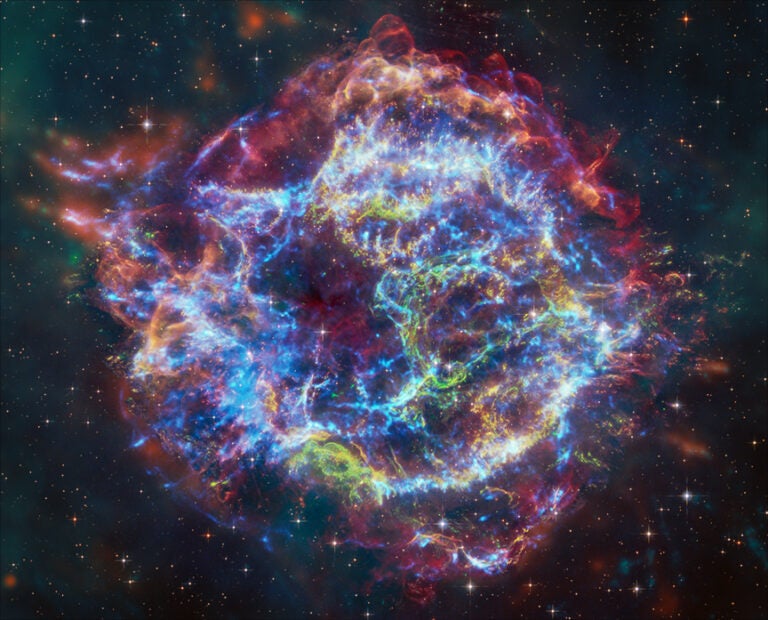

Massive stars, those tens to hundreds of times the mass of the Sun, are the key architects of galaxy evolution that contribute to the observed outflow differences between small and large galaxies. Thanks to their supersonic winds and spectacular end-of-life supernovae explosions, massive stars can fling away the dust and gas that galaxies need to form new stars. But just how different types of galaxies lose or retain their star-forming material is one thing astronomers are still trying to tease out with a new galaxy atlas.

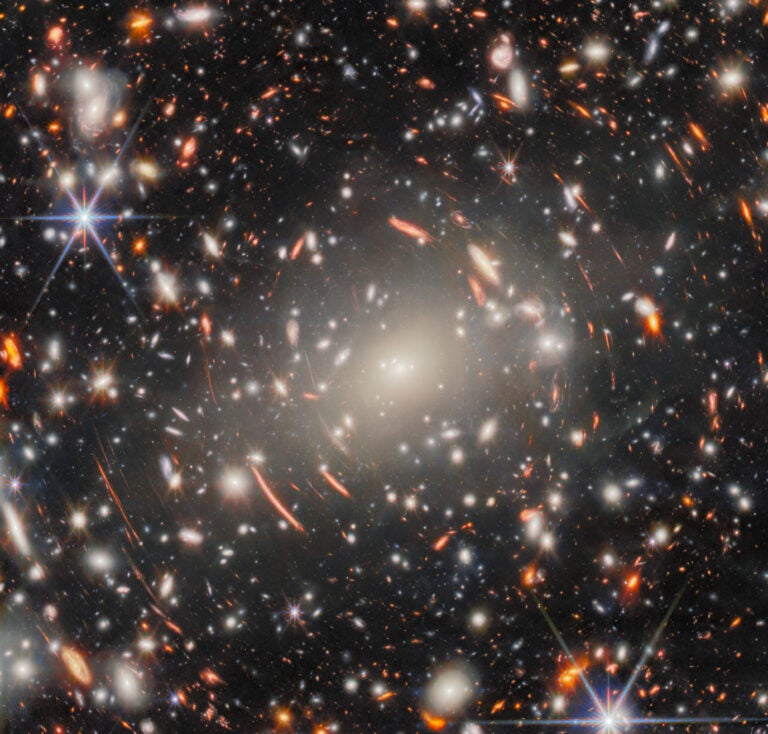

To understand the drivers of galaxy evolution, astronomers used the Hubble Space Telescope to collect far-ultraviolet light from 45 of our galactic neighbors. They then compiled the observations to create an unprecedented atlas called CLASSY, short for the COS Legacy Archive Spectroscopic SurveY. Although astronomers have previously look at star-forming galaxies in far-ultraviolet light, most of those observations were of limited or low resolution.

“CLASSY is the first time that we’ve had a uniform sample spanning all the galaxy mass ranges,” co-author Danielle Berg, astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin and principal investigator of CLASSY, tells Astronomy. “Before we had spotty evidence in different places, with lot of evidence at the high mass end. But the CLASSY sample actually spans all the way down to dwarf galaxies.”

Using the publicly available CLASSY database, the astronomers found smaller galaxies eject as much as 10 times the material as larger galaxies, relative to the rate at which they form new stars. The team also noted that the observed relationship between galaxy size and the amount of material ejected didn’t exactly match what’s predicted by accepted models. This suggests that the theories informing those models need further refined before astronomers can accurately describe how galaxies really evolve.

“It means that we’re just starting to understand what’s actually driving the feedback that controls and regulates star formation and the growth of galaxies,” says Berg. “These observations will help us constrain [formation] theories.”

Understanding how massive stars materially affect galaxies is critical to understanding why some galaxies retain enough material to continue forming stars, while others loose too much too fast and ultimately die off. The information gleaned from observing nearby galaxies is also key to understanding the universe’s first galaxies, which are much more difficult to observe.

“With the James Webb [Space Telescope] we’ll see into the distant universe, deeper down to the smaller galaxies and the smaller building blocks,” says Berg. “The idea is no matter how distant of a galaxy you observe, you’ll be able to find a galaxy in CLASSY that has similar properties, and so you can use it to interpret [the distant galaxy].

The CLASSY atlas is already drawing attention from other astronomers excited to dive into the new data. The atlas is “a major step forward, both in science and in public service,” says astronomer Daniela Calzetti of the University of Massachusetts, who was not involved in the new work. “I expect great science will come out of it.”