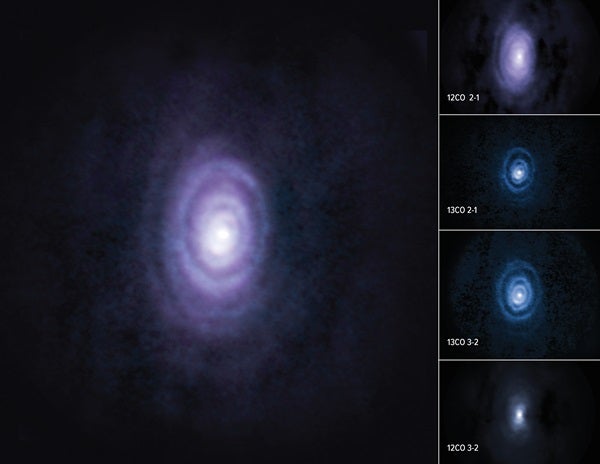

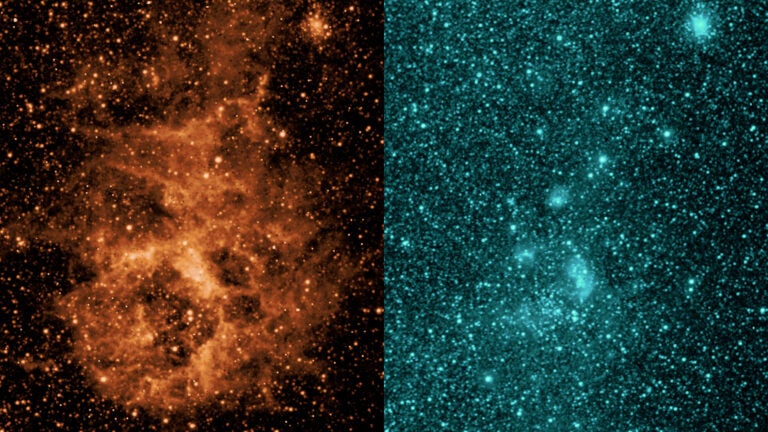

The carbon-rich star V Hydrae has been steadily puffing out layers of gas during the end of its life, enabling researchers to learn more about the evolution of aging giant stars. Over time, the stellar smoke rings have created a disc-shaped structure astronomers call a DUDE, or Disk Undergoing Dynamical Expansion (if you’re not into the whole brevity thing).

Located 1,300 light-years away in the constellation Hydra the Water Snake, V Hydrae sports six rings, hourglass-shaped features, and jet-like emissions. Due to its complex nature, astronomers recently investigated it using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array and data from the Hubble Space Telescope.

V Hydrae is classified as an asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star: an evolved, cooler red giant that shares a similar or larger mass to our own Sun. Because it is not large enough to go off as a supernovae, it will most likely continue shedding matter over time, eventually becoming a white dwarf.

According to a National Radio Astronomy Observatory release last month, what makes this cosmic object particularly fascinating to researchers is that its wide-scale plasma eruptions occur roughly every 8.5 years.

“Our study dramatically confirms that the traditional model of how AGB stars die — through the mass ejection of fuel via a slow, relatively steady, spherical wind over 100,000 years or more — is at best, incomplete, or at worst, incorrect,” said Raghvendra Sahai, an astronomer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in the release. “It is very likely that a close stellar or substellar companion plays a significant role in their deaths, and understanding the physics of binary interactions is both important across astrophysics and one of its greatest challenges.”

The team now thinks that the star has been expelling its atmosphere outward in a series of rings, as well as releasing intermittent high-speed jets of gas, over the course of the past roughly 2,100 years.

After discovering the discharges in 1981, researchers have struggled to catch stars in this stage of evolution, as they have only found a few sharing similar characteristics to V Hydrae. But studying the impact of how AGB die has far-reaching implications.

“Each time we observe V Hya with new observational capabilities, it becomes more and more like a circus, characterized by an even bigger variety of impressive feats. V Hydrae has impressed us with its multiple rings and acts, and because our own Sun may one day experience a similar fate, it has us at rapt attention,” Sahai said in the release.