Key Takeaways:

- Analysis of Tutankhamun's iron dagger revealed its blade was forged from meteoric iron, evidenced by high nickel and cobalt content, a Widmanstätten pattern, and the presence of troilite, confirming its extraterrestrial origin.

- The dagger's creation involved low-temperature heat forging, excluding cold and hot working techniques based on the observed metallurgical characteristics.

- The dagger's gold hilt utilized lime plaster as an adhesive, a technique not common in ancient Egypt during Tutankhamun's time but prevalent in the Mitanni and Hittite regions.

- The presence of lime plaster, combined with historical records from the Amarna letters detailing an iron dagger gifted from the Mitanni king to Amenhotep III (Tutankhamun's grandfather), suggests the dagger's origin lies outside of Egypt.

When archaeologists peered inside Tutankhamun’s tomb for the first time in the early 1920s, they found antechambers packed to the brim with thousands of artifacts: statues, furniture, jewelry, clothes, chariots, paintings. Among these possessions was an iron dagger — just over one foot in length and crafted from an iron meteorite — that would puzzle researchers for nearly a century.

It’s easy to see why the researchers might be confused. The Iron Age, a period when people across Europe, Asia and Africa began making tools from iron ore through a process called smelting, is generally thought to have begun no earlier than 1200 B.C. — some 150 years after King Tut’s death. If smelting was off the table, archaeologists wondered, how might the dagger have been made?

Takafumi Matsui, director of the Chiba Institute of Technology’s Planetary Exploration Research Center in Japan, and his colleagues visited the weapon at the Egyptian Museum of Cairo in 2020 to find out. “A number of manufacturing processes are possible,” they wrote in a recent study in Meteoritics & Planetary Science, “such as cold working, in which an iron meteorite is cut and polished; hot working, involving high-temperature melting and subsequent casting; or low-temperature heating and subsequent forging.”

But their chemical analyses of the dagger’s blade and gold hilt, combined with historical knowledge of ancient manufacturing techniques, now cast doubt on whether it was crafted in ancient Egypt at all. Instead, Matsui and his colleagues propose that the king of the nearby Mitanni empire gave the dagger to King Tut’s grandfather as a wedding gift.

Lines of evidence

Although some prehistoric iron artifacts are known to have been forged from meteorites, the cosmic source of the iron in the late pharaoh’s dagger wasn’t confirmed until a team of Italian researchers analyzed its elemental composition for the first time in 2016. While Earth-based iron contains about 4 percent nickel, the team found that the blade’s higher nickel concentration (and trace amounts of cobalt) was instead consistent with space rock.

Four years later, aided by the Grand Egyptian Museum’s conservation center, Matsui and his colleagues used a portable scanning X-ray fluorescence instrument to map out the elements on the surface of the blade; not just iron, nickel and cobalt, but also chlorine and manganese, among others. They found that the bumpy, black spots along its edges and center, for example, likely originated from troilite — a mineral commonly found in iron meteorites — but had lost a large amount of sulfur after being heated around 1,300 degrees Fahrenheit (705 Celsius).

And just as informative as the abundance of these elements is their arrangement. “In some places, discontinuous banded arrangements with cubic symmetry and bandwidth of about 1 [millimeter] are observed,” the authors wrote. This three-dimensional, cross-hatched texture, known as a Widmanstätten pattern, occurs in some meteorites if their iron-nickel mixtures separate into bands upon cooling. The pattern is only visible after the rock has been cut, polished and acid-etched, but its near-hidden and lasting presence on King Tut’s dagger reveals that the blade was never heated above 1,700° F (927° C).

Through the process of elimination, the researchers threw both cold working and hot working techniques out the window: “These lines of evidence lead to a conclusion that the Tutankhamen iron blade was made by low-temperature heat forging,” Matsui and his colleagues write. But they had yet to solve the mystery of who made it.

A wedding gift

The team turned to the dagger’s gold hilt, decorated with intricate patterns of fine gold grains and stones of lapis lazuli, carnelian and malachite. During King Tut’s reign, ancient Egyptians commonly used organic glue to attach gold powders and gold leaf on wood. This is true of the gilded wood samples found in the pharaoh’s tomb. But high amounts of calcium detected on his dagger’s hilt suggest that its artisans used a stronger adhesive instead: lime plaster, composed of sand, water and calcium oxide (lime).

This was somewhat surprising. After all, much like smelting, the use of lime plaster in ancient Egypt only began to take off after King Tut’s death, during the Ptolemaic period. Both iron processing technology and lime plaster, however, were already prevalent in the northerly Mitanni and Hittite regions. “The [calcium]-bearing, sulfur-lacking plaster used on the gold hilt may support the idea that the Tutankhamen meteoritic iron dagger was brought as a gift from Mitanni, as recorded in the Amarna letters,” conclude the researchers.

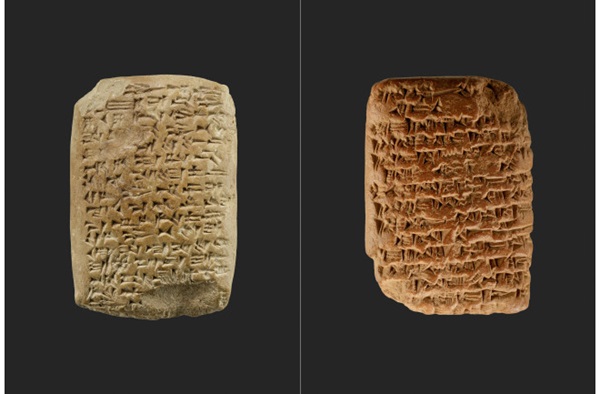

The 3,400-year-old Amarna letters, hundreds of clay tablets considered to be the oldest documents of diplomacy ever found, consist of correspondences written between Egyptian pharaohs and nearby kings. One such letter mentions a list of gifts made of iron — including an iron dagger with “an inlay of genuine lapis lazuli” and a gold sheath — that the king of Mitanni sent to King Tut’s grandfather, Amenhotep III, when the pharaoh married a princess from the region.

Although it would seem the various puzzle pieces have fallen perfectly into place, it will be the job of future studies to confirm whether the family heirloom mentioned in the Amarna letter is indeed the very dagger currently sitting in the Museum of Cairo. Until then, we can all agree on one thing: The bar for wedding gifts has certainly been raised.