The icy, potentially habitable saturnian moon Enceladus, which sports intriguing plumes that spray material into space, “may be one of our best chances to find extant [still existing] life in our solar system,” according to Regis Ferriere, Associate Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Arizona. The most recent decadal survey for planetary science proposes a dedicated mission to Enceladus that would arrive in the 2050s.

Mars will stay in the spotlight through the 2030s thanks to a sample return mission. But in the 2040s, Uranus will take center stage, and Saturn’s moon Enceladus will steal the show in the 2050s. That’s according to the goals outlined in the latest decadal survey for planetary science.

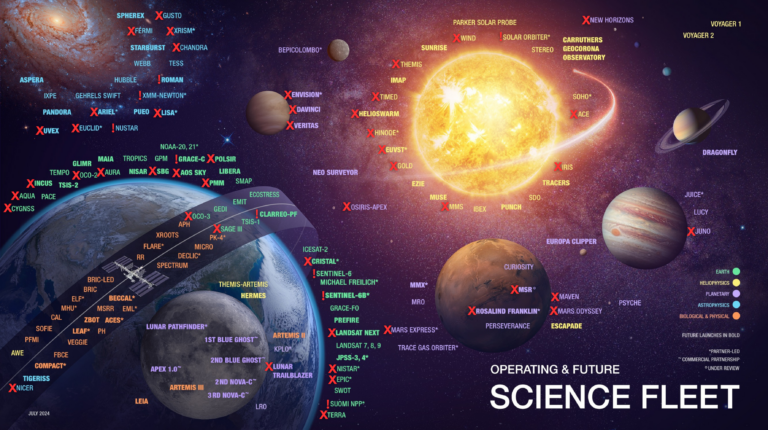

With the release of “Origins, Worlds, and Life: A Decadal Strategy for Planetary Science and Astrobiology 2023-2032,” the planetary science community drafted a blueprint for how U.S. policymakers should invest limited resources available for space exploration. The decadal, the result of a steering committee that sought and received recommendations from the planetary science community, also helps set the international tone for solar system exploration.

The mission priorities? A flagship orbiter and probe to study the ice giant Uranus. A flagship mission to Enceladus that will orbit the saturnian Moon, as well as land on it. A continuing program of Mars exploration, including a sample return mission. A host of other smaller mission possibilities. And, last but not least, defending our home world against asteroid impacts.

“The decadal,” as it’s typically referred to, is the blueprint for funding agencies like NASA and the National Science Foundation. And because American-led missions often include international instruments and investigators, the decadal has resonance for the global planetary science community.

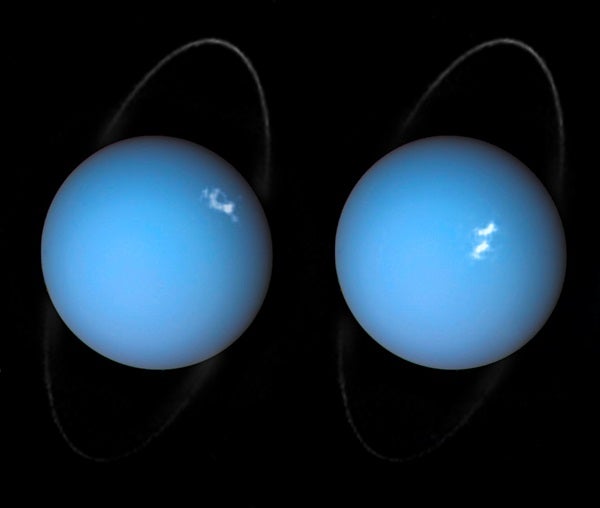

A flagship mission to Uranus

Harboring nearly 30 moons, Uranus beckons with a multi-billion-dollar mission that will be the first return to the cold gas giant since Voyager 2 flew by it in January 1986.

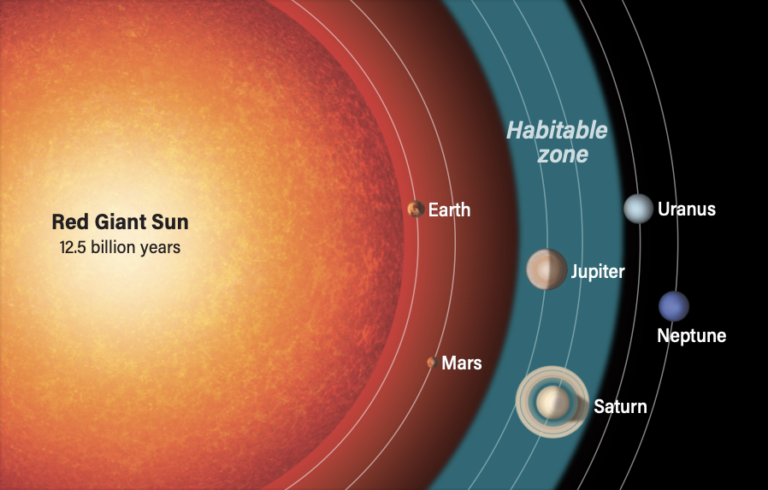

Uranus is the coldest planet in the solar system. Its core, for reasons unclear, does not shed much heat, so its cloud-top “surface” can get as chilly as about –375 degrees Fahrenheit (–224 degrees Celsius). The planet also mysteriously orbits on its side, with the poles located where equators are on other worlds. The ringed and stormy ice giant is rich in helium and hydrogen, with just enough methane to lend the world its signature blue hue. The planned mission would be launched during the 2030s and arrive at Uranus sometime around 2044.

A scientist who has studied gas giants, Ravit Helled at the University of Zurich, told Astronomy that when it comes to the ice giants “we have more questions than answers and the only way to improve our knowledge is to collect more data and have a dedicated flagship mission.”

Helled says that “Uranus and Neptune are still poorly understood and there are many key open fundamental questions about them, such as: How did they form and evolve? What are they made of? What are the rotation rates (length of day) of these planets? How are the magnetic fields generated? Does it have a core? … ”

She adds that Uranus is “special because it seems to be in thermal equilibrium with the Sun,” but exactly why remains a mystery. “Uranus and Neptune are known as ‘ice giants,’” she says, “and we still don’t know how much water they actually have.”

Helled believe that a mission to Uranus “will not only teach us about the conditions in the solar nebula from which the solar system formed, but will also reflect on our understanding of the many exoplanetary systems consisting of Uranus-like planets.”

Exploring the enigma of Enceladus

Despite being a rather small, Saturn’s 310-mile-wide (500 km) moon Enceladus also received star-treatment in this latest decadal report. That’s partly because the Cassini mission saw plumes of erupting liquid on Enceladus in 2005. And where there’s water, the chances for life go way, way up. The plumes also contained unusual amounts of possible biosignatures, such as methane, which can be a byproduct of biology.

The proposed “Orbilander” mission would arrive at Enceladus in the 2050s, orbit the moon for 18 months, then the entire craft would descend to the moon’s surface. By then, it will have flown through a few of those intriguing plumes, which are so active that their rejected material creates a thin ring around Saturn.

Once on the surface, the Orbilander would spend two years hunting for signs of biology. Enceladus’ surface is relatively safe for spacecraft, as it lacks the intense radiation baths of, for example, Jupiter’s moon Europa. According to NASA, “Enceladus has most of the chemical ingredients needed for life, and likely has hydrothermal vents spewing out hot, mineral-rich water into its ocean.”

Astrobiologists are particularly excited by the proposed Enceladus mission. University of Arizona Associate Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Regis Ferriere — who is a mathematician with an ecological bent — tells Astronomy that “Enceladus may be one of our best chances to find extant [still existing] life in our solar system.”

Ferriere was part of a team that published a 2021 paper in Nature Astronomy suggesting that the data Cassini produced shows “the observed plume composition is a likely outcome in model simulations that include the microbial activity, whereas it is an unlikely outcome in the simulations that only include the abiotic [non-biological] processes.”

In other words, the chemicals found in Enceladus’ plumes would make more sense if microbes were involved. And that’s where the new mission comes in.

“We won’t know with just the Cassini data,” says Ferriere. “The Orbilander is a fantastic opportunity to gather new data that could solve the mystery. The Orbilander is designed to characterize organic molecules in the plume, and thus has the potential to detect the building blocks of Earth-like cells, such as amino acids or lipids.”

But even if the orbilander finds the chemistry of the Enceladus plumes is not produced by life, Ferriere says the data would be important: “We would still learn a great deal about the habitability of Enceladus and, more generally, of extraterrestrial environments that harbor liquid water.”

Mars, Titan, the Moon, and more

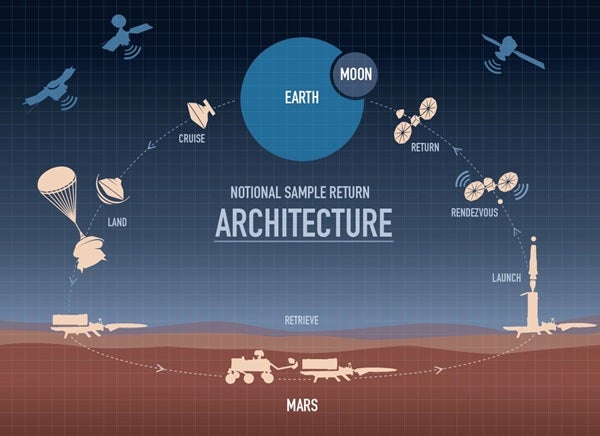

Getting Mars rocks to Earth is another top priority, one already baked into current operations on the Red Planet. The Perseverance rover is collecting and caching samples to be returned with a future sample return mission. Retrieving and launching these samples from Mars back to Earth is estimated to cost more than the other flagship missions, clocking in at around $5.3 billion.

The decadal also outlined a number of possibilities for two smaller missions, including proposed flights to Triton, Titan, Venus, and asteroids. Another option is a Mars lander that would drill into martian ice, looking for signs of life while also studying the planet’s geophysical properties.

Yet another possibility is a mission that would return samples collected from our Moon’s south pole by Artemis astronauts — fitting with the decadal’s emphasis that science must be at the core of humanity’s long-awaited return to the Moon.

Keeping watch on near-Earth space

Planetary defense took a hit in the last NASA budget request, thanks to a temporary delay in funding for the Near-Earth Object (NEO) Surveyor mission, an infrared space telescope meant to scan for potentially hazardous space rocks. However, this decadal prioritizes the NEO Surveyor mission.

The report also expresses concern about the proliferation of satellite constellations, proposes increasing budgets for smaller planetary missions, and emphasizes the need to precisely track, identify, and rectify problems in diversity, equity, and inclusion within the planetary sciences community.

All in all, the latest decadal survey for planetary science and astrobiology has been well-received. The largest space-science advocacy group in the world, The Planetary Society, praised the decadal.

However, carrying out these ambitious plans will require money. According to Arizona State researcher Jim Bell, who helped prepare the Society’s official reaction: “In my opinion, securing the funding for the recommended program over the next decade is likely to be the biggest challenge faced by those who support the exciting and ambitious portfolio of planetary science and planetary missions recommended in the survey.”