Key Takeaways:

Hot, dry winds blowing across the Sahara Desert have driven an enormous plume of dust more than 3,500 miles (5,630 kilometers) across the Atlantic Ocean.

As of June 6, 2022, the plume stretched from Africa to South America and even reached Puerto Rico. All told, it covered more than 2.2 million square miles (5.7 million square kilometers) of the tropical Atlantic Ocean. It’s expected to blow into the Gulf of Mexico by the weekend — and cause dramatic sunsets in Florida and other locations.

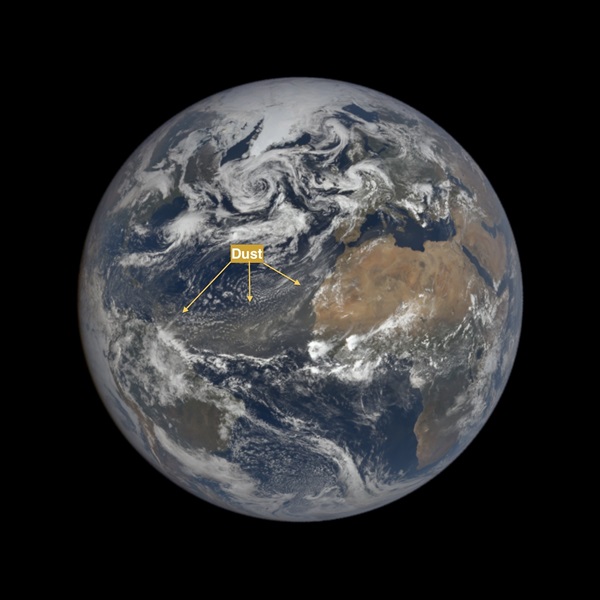

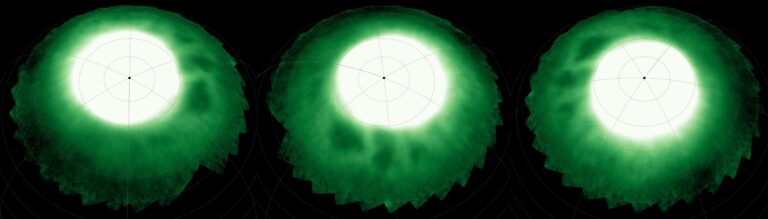

Visible from almost a million miles away

The plume was so large and distinct that it was seen by the DSCOVR spacecraft stationed 984,628 miles (1,584,605 km) from Earth:

On average, the trade winds sweep an estimated 180 million metric tons of Saharan dust across the Atlantic Ocean to different parts of the Americas and the Caribbean Basin every year. So the phenomenon is not all that unusual.

Scientists call it the Saharan Air Layer. The SAL is characterized by a mass of very dry, exceedingly dusty air that forms over the Sahara Desert during the late spring, summer and early fall and frequently sweeps out into the Atlantic.

SAL activity typically ramps up in mid-June and peaks from late June to mid-August, with new outbreaks occurring every three to five days, according to Jason Dunion, a University of Miami hurricane researcher. During this peak period, SAL outbreaks often reach as far west as Florida, Central America and even Texas. And they can cover areas of the Atlantic as large as the lower 48 United States.

In 2020, a late-June event was so enormous that it was dubbed the “Godzilla” dust plume. It intruded into the southern United States, where on June 27 it raised the concentration of fine particulates (PM 2.5) to a level exceeding the EPA air quality standard in about 40 percent of stations in the South.

Will the current plume go on to rival Godzilla? That remains to be seen.

One thing is sure: Saharan plumes blowing across the Atlantic suppresses hurricane activity. The warm air layer tends to quell updrafts of moist air that are key to storm formation. In addition, by shading the ocean, the dust can help keep sea surface temperatures down. Warm sea water fuels storms, so this tends to suppress them. And any storms that do manage to form are prone to being ripped apart by the strong winds associated with the Saharan Air Layer.