Billions of years from now, as our Sun approaches the end of its life and helium nuclei begin to fuse in its core, it will bloat dramatically and turn into what’s known as a red giant star. After swallowing Mercury, Venus and Earth with hardly a burp, it will grow so large that it can no longer hold onto its outermost layers of gas and dust.

In a glorious denouement, it will eject these layers into space to form a beautiful veil of light, which will glow like a neon sign for thousands of years before fading.

The galaxy is studded with thousands of these jewel-like memorials, known as planetary nebulae. They are the normal end stage for stars that range from half the Sun’s mass up to eight times its mass. (More massive stars have a much more violent end, an explosion called a supernova.) Planetary nebulae come in a stunning variety of shapes, as suggested by names like the Southern Crab, the Cat’s Eye and the Butterfly. But as beautiful as they are, they have also been a riddle to astronomers. How does a cosmic butterfly emerge from the seemingly featureless, round cocoon of a red giant star?

Observations and computer models are now pointing to an explanation that would have seemed outlandish 30 years ago: Most red giants have a much smaller companion star hiding in their gravitational embrace. This second star shapes the transformation into a planetary nebula, much as a potter shapes a vessel on a potter’s wheel.

The dominant theory of planetary nebula formation previously involved only a single star — the red giant itself. With only a weak gravitational hold on its outer layers, it sheds mass very rapidly near the end of its life, losing as much as 1 percent per century. It also churns like a boiling pot of water underneath the surface, causing the outer layers to pulse in and out. Astronomers theorized that these pulsations produce shock waves that blast gas and dust into space, creating what’s called a stellar wind. Yet it takes a great deal of energy to expel this material completely without having it fall back into the star. It cannot be any gentle zephyr, this wind; it needs to have the strength of a rocket blast.

After the star’s outer layer has escaped, the much smaller inner layer collapses into a white dwarf. This star, which is hotter and brighter than the red giant it came from, illuminates and warms the escaped gas, until the gas starts glowing by itself — and we see a planetary nebula. The whole process is very fast by astronomical standards but slow by human standards, typically taking centuries to millennia.

Until the Hubble Space Telescope launched in 1990, “we were pretty sure we were on the right track” toward understanding the process, says Bruce Balick, an astronomer at the University of Washington. Then he and his colleague Adam Frank, of the University of Rochester in New York, were at a conference in Austria and saw Hubble’s first photos of planetary nebulae. “We went out to get coffee, saw the pictures and we knew that the game had changed,” Balick says.

Astronomers had assumed that red giants were spherically symmetrical, and a round star should produce a round planetary nebula. But that’s not what Hubble saw — not even close. “It became obvious that many planetary nebulae have exotic axisymmetric structures,” says Joel Kastner, an astronomer at the Rochester Institute of Technology. Hubble revealed fantastic lobes, wings and other structures that weren’t round but were symmetric around the nebula’s main axis, as if turned on that potter’s wheel.

A 2002 article by Balick and Frank in the Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics captured the debate at the time over the origin of these structures. Some scientists proposed that the axial symmetry stemmed from how the red giant star rotated or how its magnetic fields behaved, but both ideas failed some fundamental tests. Both rotation and magnetic fields should get weaker as the star grows larger, yet the mass-loss rate of red giants accelerates at the end of their lifetimes.

The other option was that most planetary nebulae are formed not by one star, but by a pair of stars — what Orsola De Marco, an astronomer at Macquarie University in Sydney, named the “binary hypothesis.” In this scenario, the second star is much smaller and thousands of times fainter than the red giant, and it might be as far away as Jupiter is from the Sun. That would allow it to disrupt the red giant while being distant enough to not be swallowed up. (Other possibilities also exist, such as a dive-bombing orbit in which the second star would approach the red giant every few hundred years, peeling off layers from it.)

The binary hypothesis accounts very well for the first stage of metamorphosis of a dying star. As the companion pulls dust and gases away from the primary star, they do not immediately get sucked into the companion, but form a swirling disk of material known as an accretion disk in the orbital plane of the companion. That accretion disk is the potter’s wheel. If the disk has a magnetic field, it will propel any charged gases out of the plane of the disk and toward the axis of rotation. But even without a magnetic field, the material in the disk impedes the outward flow of gases in the orbital plane, so the gas will take on a bilobed structure, with faster flow toward the poles. And that’s just what Hubble saw in its images of planetary nebulae. “Why look for a really complicated explanation when a companion star explains it really well?” says De Marco.

Nevertheless, the idea of undetectable companion stars didn’t sit well with some astronomers. As recently as 2020, writes Leen Decin, an astronomer at KU Leuven in Belgium, a famous astrophysicist told her “You know, Leen, it all looks so fantastic, the observations are so fascinating, the current state-of-the-art models seem to do a pretty good job for interpreting the data, but in the end, shouldn’t we only believe what we can actually see?”

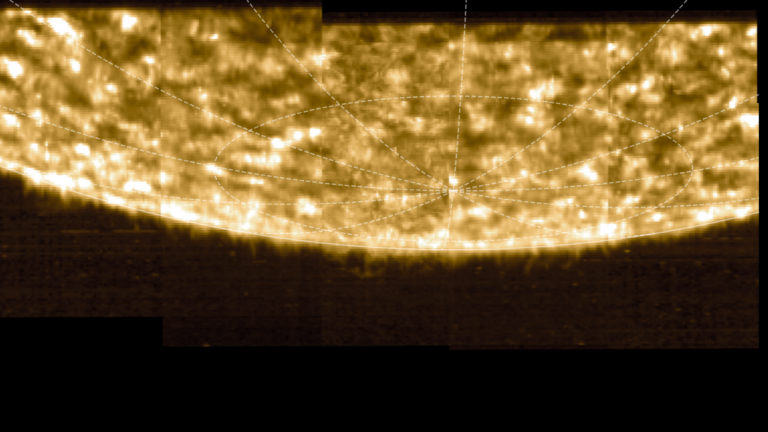

But over the last 10 to 15 years, the tide has steadily turned. New and innovative telescopes have revealed that some red giants are surrounded by spiral structures and accretion disks before they turn into planetary nebulae — just as expected if there were a second star pulling material off the red giant. In a couple of cases, astronomers may have even spotted the companion star itself.

Decin and her colleagues have especially relied upon the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, which came online in 2011. ALMA consists of 66 radio telescopes that work together to produce images of astronomical objects. “It gives us high spatial and spectral resolution that are important if you want to understand dynamics and velocity,” Decin says. Velocity is an important part of the puzzle for scientists to map stellar winds and accretion disks.

ALMA has seen spiral-shaped or arc-shaped structures around more than a dozen red giant stars, almost certainly a sign that matter is being shed from the red giant and spiraling toward its companion. The spirals closely match computer simulations and are impossible to explain with the old stellar-wind model. Decin reported the initial findings in 2020 in Science and expanded on them the following year in Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics.

In addition, Decin’s group may have spotted the previously undetectable companions of two red giants, p1 Gruis and L2 Puppis, in ALMA images. To make sure, she needs to monitor them over a period of time to see if the newly detected objects are moving around the primary star. “If they move, I’m sure that we have companions,” says Decin. Perhaps this discovery will win over the last skeptics.

Like crime scene investigators, astronomers now have “before” and “after” snapshots of the creation of a planetary nebula. The one thing they lack is the equivalent of CCTV footage of the event itself. Is there any hope that astronomers can catch a red giant in the act of turning into a planetary nebula?

So far, computer models are the only way to “watch” the centuries-long process unfold from beginning to end. They have helped astronomers home in on one dramatic scenario, in which the companion star plunges into the primary after a prolonged period of orbiting it and losing distance due to tidal forces. As it spirals toward the red giant’s core, the companion sheds “an insane amount of gravitational energy,” says Frank. The computer models show that this hugely accelerates the process through which the star lets go of its outer layers, to just one to 10 years. If this is correct, and if astronomers knew where to look, they could witness the death of a star and birth of a planetary nebula in real time.

One candidate to keep an eye on is called V Hydrae. This very active red giant star ejects bullet-like clumps of plasma toward its poles every 8.5 years, and it also has coughed out six large rings in its equatorial plane over the last 2,100 years. Raghvendra Sahai, an astronomer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who published the discovery of the rings in April, believes that the red giant has not one but two companion stars. A nearby companion may already be grazing the red giant’s envelope and producing the plasma ejections, while a distant companion in a dive-bombing orbit controls the ejection of the rings. If so, V Hydrae may be close to swallowing up its closer companion.

Finally, what about our Sun? Studies of binary stars might seem to have little relevance for our star’s fate, because it is a singleton. Stars with companions lose mass about six to 10 times faster than those without, Decin estimates, because it’s much more efficient for a companion star to pull off a red giant’s shell than for the red giant to push off its own shell.

This means that data on stars with companions cannot reliably predict the fate of stars without companions, like the Sun. Roughly half of the stars that are the Sun’s size have companions of some sort. According to Decin, the companion will always affect the shape of the stellar wind, and it will significantly affect the mass-loss rate if the companion is close enough. The Sun will most likely eject its outer layer more slowly than those stars and will stay in its red-giant phase several times longer.

But a great deal is still unknown about the Sun’s last act. For example, even though Jupiter is not a star, it could still be hefty enough to attract material from the Sun and power up an accretion disk. “I think we’ll have a very small spiral created by Jupiter,” Decin says. “Even in our simulations, you can see its impact on the solar wind.” If so, then our Sun too might be in line for a showy grand finale.

This article originally appeared in

Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews. Sign up for the

newsletter.