After two decades and $10 billion — as well as a Congressional effort to kill the project — the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has finally delivered its first batch of science images. And, simply put, wow.

Yesterday (July 11), President Biden hosted a press briefing in which he presented the first teaser image from JWST. The image, the deepest infrared shot ever taken, shows a foreground galaxy cluster called SMACS 0723 that is acting as gravitational lens, revealing much more distant galaxies behind it. Due to their extreme distances, these ancient galaxies are heavily redshifted, appearing like bright orange-red tadpoles in a cosmic whirlpool.

Whereas the Hubble Space Telescope required weeks to take such deep-field shots, JWST spent only 12.5 hours to grab this view of SMACS 0723 and beyond. It’s more than just a pretty picture, too, as JWST’s impeccable infrared vision even allowed researchers to determine the basic chemical composition of a 13.1 billion-year-old galaxy in the background.

JWST: The start of something special

Based on the quality of yesterday’s deep image, as well as the other breathtaking images released today (July 12) during a livestream on NASA TV, the world’s largest and most powerful space telescope is clearly going to be a juggernaut.

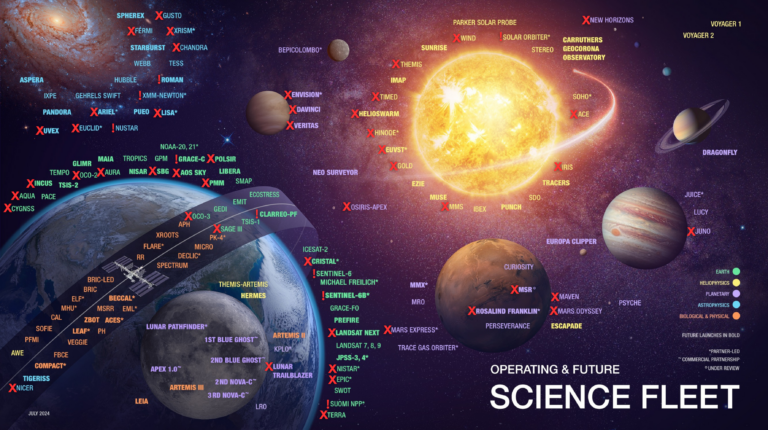

The remaining images released today, selected by a team of representatives from NASA, the Space Telescope Science Institute, the Canadian Space Agency, and the European Space Agency, spanned a range of different types of targets that JWST will investigate throughout its mission. Today’s targets include two nebulae, a tight group of interacting galaxies, and a strange exoplanet in our Milky Way.

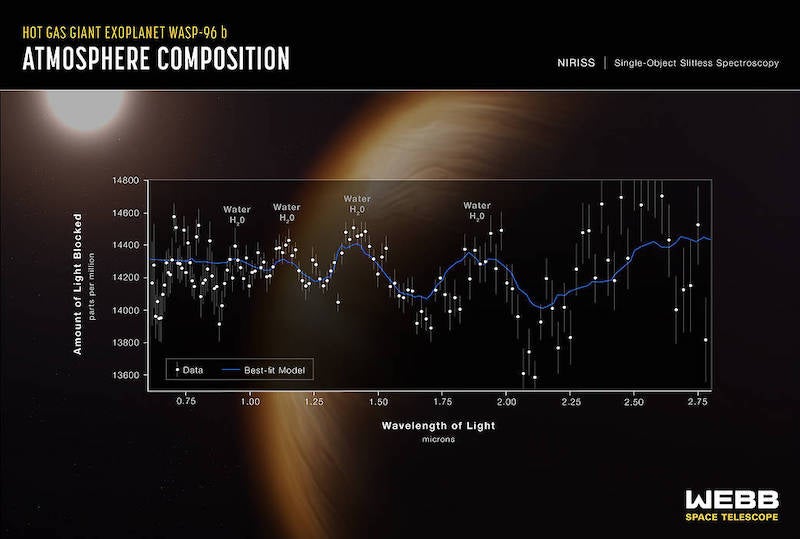

Specifically, today’s images showcase the Carina Nebula, a stellar nursery for massive stars that’s located some 7,600 light-years away; the Southern Ring Nebula, the ejected remains of a dying star located some 2,000 light-years away; Stephen’s Quintet, a compact interacting galaxy group located some 290 million light-years away; and WASP-96 b, a hot gas giant that orbits its star every 3.4 days and is located more than 1,000 light years away.

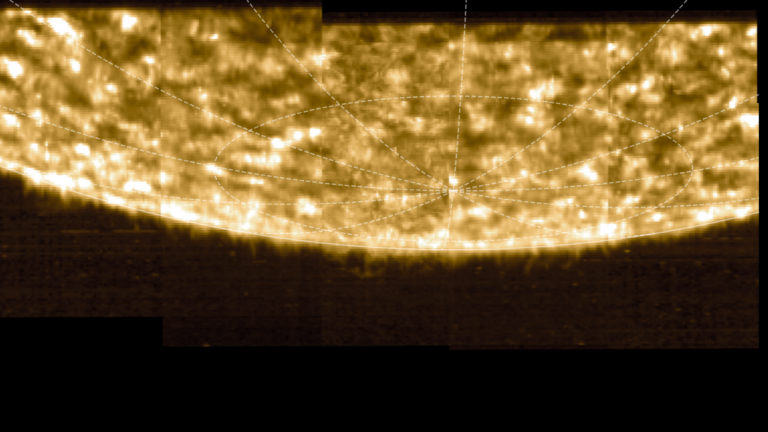

The Carina Nebula image presents a brown bank of a stellar nursery’s gas and dust, which gives the image the appearance of a ridge silhouetting the starry sky behind it. This has already earned the image the nickname Cosmic Cliffs — and it reveals hundreds of stars never-before-seen to human eyes. In this view, gas jets are seen blowing dust clear from newborn stars, and the high-resolution shot also shows structures that scientists are as yet unable to interpret. Infrared light, which JWST is built to detect, can often reveal more than visual light because infrared cuts through gas and dust. This image shows gas congealing to create stars and jets of energy sculpting the surrounding nebula, both aiding and slowing star formation.

Meanwhile, shockingly detailed views of the Southern Ring Nebula — which looks a bit like an amoeba or an algae bloom — reveal, for the first time, that one of the two stars at the nebula’s center is shrouded with dust. By using JWST to monitor the interplay of starlight, gas, and dust, over time, scientists will gain a much better sense of the dynamics of dying stars such as this, as well as the planetary nebulae they produce.

The Stephen’s Quintet imagery shows a bright heart of heated materials falling into a black hole at the center of a galaxy. The data and imagery reveal new information about the temperatures and motions of the gas that will allow astrophysicists to better understand what happens around black holes. In near- and mid-infrared wavelengths, JWST also captured individual stars within the galaxies that make up Stephen’s Quintet, revealing highly specific, never-before-seen interactions in the group as star birth is triggered.

JWST also took a spectrum of the exoplanet WASP-96 b’s. By breaking down the light streaming through the planet’s atmosphere, scientists uncovered evidence of water vapor, leading them to believe WASP-96 b features something familiar to us here on Earth: clouds and hazes. While not a visually stunning image — after all, it’s a spectrum — the result shows that JWST will help astronomers make great strides at better understanding both the planets of our solar system and the rocky, Earth-like worlds that reside farther out in the Milky Way.

James Webb Space Telescope

With a 21.3 feet (6.5 meter) mirror composed of 18 gold-plated hexagons, a tennis-court sized Sun shield, and four high-tech instruments working in visible and near-to-mid infrared wavelengths, the James Webb Space Telescope currently resides about a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from Earth. It orbits the Sun at a point called L2, where competing gravitational forces from the Earth and Sun keep it in a relatively stable orbit.

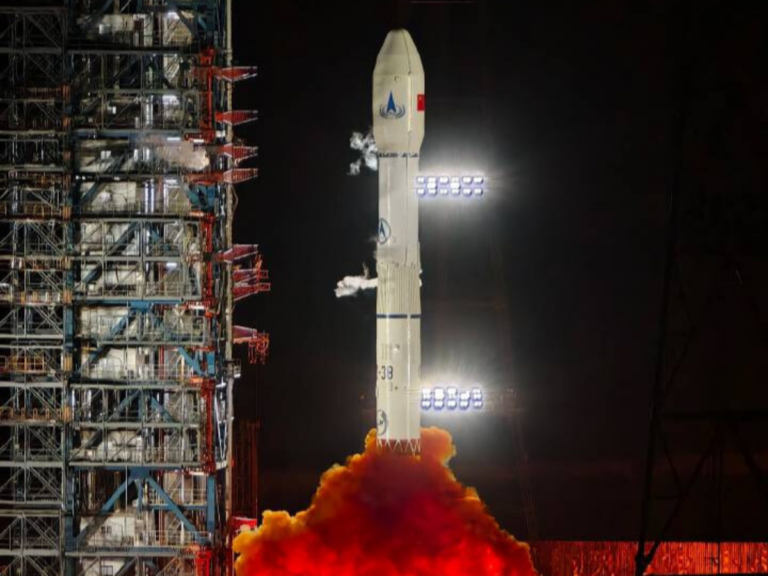

JWST launched on Christmas Day 2021 from French Guiana and has performed flawlessly since then. And that’s very good news, too. Unlike Hubble, which resides in low-Earth orbit, JWST is too far away to be serviced. If it breaks down, that’s it for the $10-billion mission.

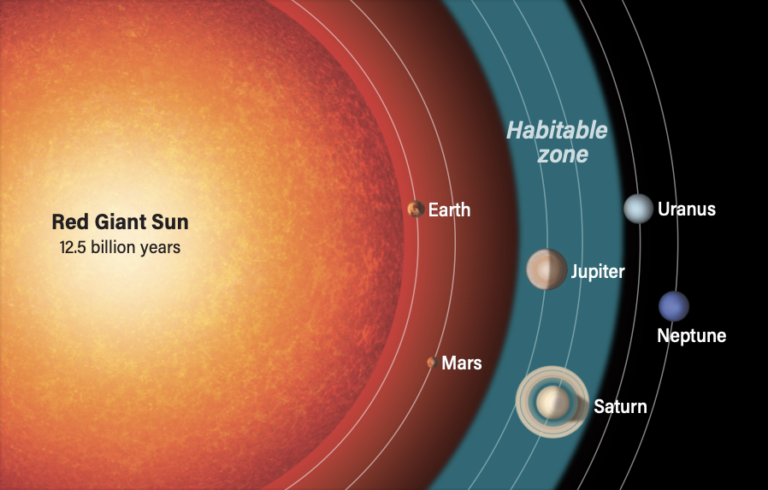

In other words, a great deal is riding on this dream instrument for astronomers. With the help of JWST, researchers plan to study everything from the evolution of the early universe to potentially habitable exoplanets. And this week’s images are just the beginning of science returns that promise to revolutionize many aspects of astronomy for decades to come.