Key Takeaways:

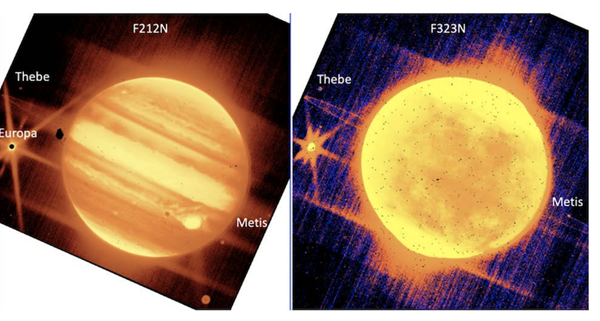

- The James Webb Space Telescope's (JWST) Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) captured commissioning images of Jupiter, revealing prominent features such as the Great Red Spot, several moons (Europa, Metis, Thebe), and surprisingly distinct views of the planet's faint rings, underscoring its capabilities for solar system target tracking and spectral analysis.

- Astronomers Stephen Kane and Zhexing Li investigated the paradox of Jupiter possessing only thin, hazy rings despite its immense mass, proposing that its extensive dynamical history should theoretically provide ample material for a more substantial ring system.

- Their computer simulations demonstrated that Jupiter's massive Galilean moons play a critical role in preventing the sustained existence of large icy rings by gravitationally disrupting particle orbits or accreting ring material, leading to the hypothesis that "Massive planets form massive moons, which prevents them from having substantial rings."

- The findings suggest that the presence or absence of robust ring systems in exoplanets can offer significant insights into their dynamical past, age, moon configurations, and the availability of volatile materials, thereby aiding in the understanding of planet formation and evolution beyond our solar system.

Shortly after releasing the spectacular first images from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in early July, NASA uploaded the telescope’s commissioning data to its online archive as well. These data show off the observatory’s ability to track targets — including planets and asteroids in our solar system — and pick apart their reflected light to provide details about their chemical composition.

Among those images were some stunning snaps of Jupiter, taken by JWST’s NIRCam through several infrared filters. Visible are features such as Jupiter’s thick, tumultuous cloud belts and its iconic Great Red Spot, a perpetual storm roughly the size of Earth. But there are a few extra members of the family photobombing the beaty shots: moons Europa, Thebe, and Metis, as well as some of the planet’s thin, faint rings.

In fact, the rings’ appearance in such short, one-minute exposures “was absolutely a very pleasant surprise,” according to NIRCam instrument scientist John Stansberry, of the Space Telescope Science Institute, in a NASA blog. Stefanie Milam of the Goddard Space Flight Center, who serves as JWST deputy project scientist for planetary science, added that their presence is “absolutely astonishing and amazing.”

The case of the missing rings

Despite the fact that Jupiter has been known to humankind since ancient times and is easy to observe in detail with backyard scopes, scientists didn’t even know the planet had rings until 1979, when Voyager 1 spotted them as it flew by. That’s because, unlike Saturn, whose claim to fame is its large, bright ring system, Jupiter’s rings are thin and hazy structures that cannot be easily seen from Earth.

We now know that all the outer planets sport rings. But with Jupiter being larger than Saturn, why doesn’t Jove have larger, brighter rings to match? Is it possible that Jupiter once did sport stunning rings — and eventually lost them?

These are exactly the questions astronomers Stephen Kane and Zhexing Li of the University of California, Riverside ask in a recent paper now accepted for publication in the Planetary Science Journal. After all, as the solar system’s most massive planet, they argue in the paper, Jupiter’s history must be rife with collisions, captures, and other such events that could provide plentiful material for more substantial rings.

To solve the mystery of Jupiter’s underwhelming ring system, the pair turned to computer simulations to examine how the planetary system acts over periods of 1 million to 10 million years. Over this time, they looked at the availability and orbital stability of icy material to form rings, essentially examining how big, bright rings might form, stick around, or be destroyed. In particular, they looked at how Jupiter’s four largest satellites, the Galilean moons — Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede — affect the formation or longevity of water ice rings.

“We found that the Galilean moons of Jupiter, one of which is the largest moon in our solar system, would very quickly destroy any large rings that might form,” Kane said of their simulations’ results in a press release. In part, that’s because the massive moons can destabilize the orbit of icy particles to eject them from the system, or alternatively sweep particles up into colliding with the moon, rather than orbiting as a ring. Ultimately, Kane said, “Massive planets form massive moons, which prevents them from having substantial rings.”

This lines up with reality, too — after all, Saturn’s rings are bright because they are made largely of ice, and likely still around (depending on their age) because researchers think they are continually replenished by the many small, icy moons embedded within them. Jupiter’s dim, thin rings, by contrast, are made mostly of dust likely shed from just a few of its small moons.

So, even if Jupiter managed to build up impressive icy rings in the past, they wouldn’t have lasted long. And its present rings, small as they are, are likely quite young — less than 10 million years old. Saturn, by contrast, appears to be in a “sweet spot” in terms of its ability to build up and maintain a large, stunning ring system over longer periods of time.

Extending to exoplanets

But Kane and Li’s research tells us even more, they say. Moving beyond the solar system, the pair also considered what their findings could mean for exoplanets and their rings. After all, rings are more than just superficial decoration — they also tell the story of a planet’s dynamical past, as well as that of its environment. If forming or maintaining massive, easy-to-spot rings of ice is difficult, then finding them tells us something valuable about the planets capable of hosting such spectacles. Ring systems could reveal information such as planetary age or details about what kinds of moons must be (or must not be) present, as well as the type or availability of material like icy comets or asteroids in the planet’s solar system.

As astronomers continue to build up our catalog of known exoplanets and point JWST at them to learn more, the details these worlds reveal — including their rings — will offer a wealth of valuable insight into how stars and their planets form and evolve over time.