The Space Launch System, or SLS, is a technological leviathan. And NASA has the numbers to back it up. Below are just a few examples of the sheer size, power, and potential of the SLS, NASA’s next chariot to the Moon.

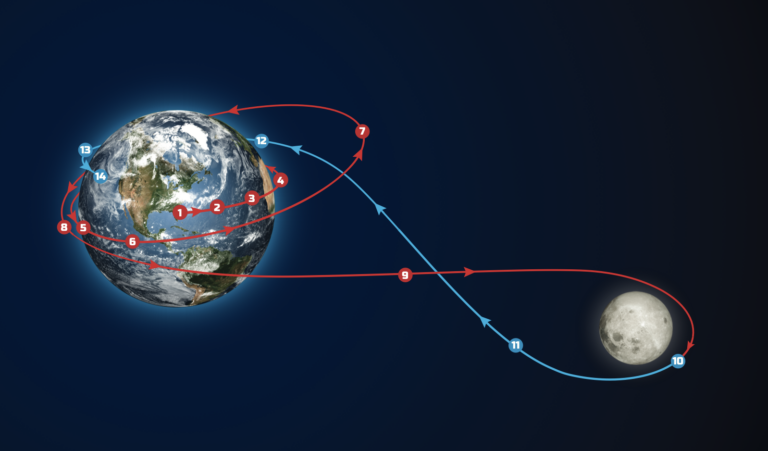

So, as Artemis 1 prepares to embark on a test run around Luna, brush up on your SLS trivia. After all, humanity’s first crewed trip back to the Moon in 50 years wouldn’t be possible without it.

- Before launch, the SLS weighs 5.75 million pounds, more than seven 777 jumbo jets at full load. The thrust of the SLS can send more than 27 tons of cargo to the Moon. For reference, the Space Shuttles were capable of ferrying 22 tons of cargo to low-Earth orbit. At 8.8 million pounds of thrust, the SLS even beats out the Saturn V, which had a thrust of some 7.5 million pounds.

- Perhaps ironically, the Space Shuttle program is part of the reason why SLS bests the Saturn. The SLS features a core stage that uses some 730,000 gallons of chilled liquid hydrogen and oxygen to fuel its four RS-25 engines. These engines, like the two solid-fuel boosters, are derived from the Space Shuttle era. In fact, this first SLS’s core stage engines are numbered: E2045, E2056, E2058 and E2060. These engines have previous proven their abilities on the Space Shuttle a total of 25 times, including a whooping 12 missions for E2045. The E2060 engine was only used on the last shuttle mission.

- There are a total of 16 shuttle-era engines ready for four more SLS rockets. After they are used, Aerojet Rocketdyne in Los Angeles will build new RS-25s, employing modern — and hopefully less costly — manufacturing techniques, according to NASA. That’s assuming the SLS is not replaced by SpaceX’s Starship, as some believe it might be (more on that later).

- The RS-25’s engines are each the size of an economy car, though just one of their dozens of small turbine blades — each the size of a quarter — produces more horsepower than a Corvette. From its four turbopumps to its nozzle, the engine’s temperature parameters span from –423 degrees Fahrenheit (–253 degrees Celsius) to some 6,000 F (3,300 C), which is like going from a temperature colder than the atmosphere of Uranus to almost three times as hot as lava.

- Despite being shuttle-era engines, the four RS-25s were tweaked to increase thrust by about five percent. They were also upgraded with engine controllers featuring the latest software and avionics. The exhaust nozzles received improved thermal coatings, too. The exhaust leaves the nozzle at 13 times the speed of sound, which would cross the United States in 15 minutes, the agency reports. It also produces clean water vapor, often called rocket rain.

- The SLS core stage is NASA’s most powerful and tallest rocket ever, standing 212 feet (65 meters) tall and 27.6 feet (8.4 m) wide. Eighty aluminum panels comprise the core stage’s 10 barrel sections, forming the forward skirt, the liquid oxygen tank section, the intertank section, the liquid hydrogen barrel, and the engine section. Nearly all the rocket’s welds lack bolts, instead having been sealed using a process called “friction stir welding.” The SLS’s distinctive orange color comes from the spray foam insulation used.

- But not every aspect of the rocket is so advanced. It also includes some cork, used for part of the thermal protection system. Engineers also incorporated hinges, bellows, and telescoping features in the fuel tanks because they shrink when filled with the super-cold fuels. Each main engine has to withstand pressures comparable to those currently faced by the Titanic, which is 3 miles (4.8 kilometers) undersea.

- The SLS core stage is numerical wonder: 100,000 clamps are used to secure its wiring and cables. The 562 cables twist through the core for a total of some 45 miles (72.5 km), and nearly 800 computer sensors are attached to them. There are three flight control computers in the core stage — two must be function for the rocket to be operational — and these computers communicate with the booster avionics and the four core stage engines.

- Meanwhile, the SLS’s twin solid-rocket boosters provide about 80 percent of the thrust during the first two minutes of flight. And their flight computers retain 80 percent of the control. The 177-feet long boosters are made of five segments that weigh, in total, 1.6 million pounds (725,000 kg). The boosters produce more than 3.2 million pounds of thrust, burning fuel at 5.5 tons per second. The SLS’s solid-rocket boosters are the biggest and most powerful ever built.

- Atop the core stage is Artemis 1 the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage, derived from a similar second stage on the Delta rocket. This is to be replaced with the more powerful Exploration Upper Stage, built by Boeing, which will have four RL-10 engines instead of just one on the ICPS. RL-10s have flown hundreds of times since its first use in the 1960s.

- Topping out at some 6 miles per second, or 21,600 miles per hour, the SLS can achieve speeds faster than an Indianapolis 500 race car — by roughly 100 times.

- The core stage first traveled from the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans to the Stennis Space Center, where it was then tested. Next, it was delivered to Kennedy Space Center and attached to the boosters, the ICPS upper stage, and the Orion capsule. To make these trips, the rocket’s components traveled on a wide barge slowly drawn by tugboats. The barge was named after the mythical Greek horse Pegasus.

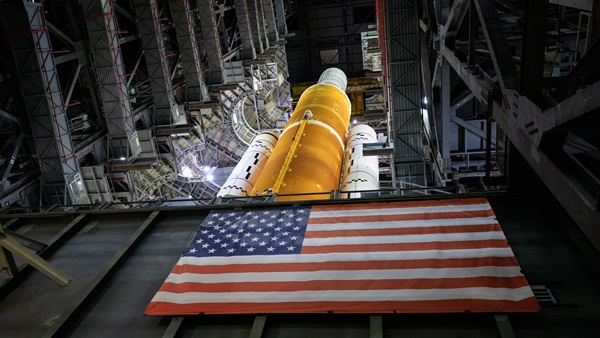

- Once all the components of the SLS were stacked inside the Cape’s Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), tested, and prepped, the VAB’s doors — nearly 500 feet (150 m) tall, the world’s largest — opened over the course of 45 minutes. The SLS then traveled on the massive crawler-transporter just over 4 miles (6.4 km) to Pad 39b. Wide enough to host a baseball field, the crawlers have previously carried Saturn Vs, Saturn 1Bs, the Space Shuttle, and now, the SLS. In total, NASA’s crawlers have racked up about 5,000 miles (8,000 km) on their odometer.

- The road upon which the crawlers, well, crawl, must be conditioned, otherwise the combined weight of the crawler, the mobile launcher, and the rocket, would force the soil to “behave like a liquid,” NASA says. The crawler alone weighs about as much as 1,000 pickup trucks — nearly 7 million pounds (3.2 million kg). The rocket moved at about 1 mph (1.6 km/h), or about 1.5 feet per second (0.44 m/s).

- The SLS had rolled out earlier in the summer for the wet-dress rehearsal, a complicated set of tests, fueling, and countdown procedure simulations that had a few hiccups. Engineers overcame the leaks and other difficulties and finally declared the final iterations of the dress rehearsal a success. After returning to the VAB, SLS recently rolled out again and arrived at the Pad 39b on August 17. This time, not for a test, but for a literal moonshot.

SLS is not only a technological triumph, but also a political beast

The Space Launch System is not just a rocket. It’s a political dynamo.

“This has been in the works for years,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson told the press in the week leading up to the expected launch of the SLS for Artemis 1. “Space is hard.” And that’s true for the politics of space, too.

Nelson has compared the delays and budget overruns for SLS to those of the James Webb Space Telescope, which, he said, has since delivered stunning results. And NASA will be using different contracts in the future, emphasizing contractor efficiency by not rewarding cost overruns as the SLS program and Artemis missions move forward.

“The cost is going to come down,” Nelson says.

Over the years, the projected $10 billion budget for the SLS has doubled, and the debut of the rocket is six years past its initially planned 2016 launch target. The program, set in motion in 2010 by Congress and signed into action by President Obama, relied on modifications to Shuttle-era hardware. That, the thinking went, promised a relatively straightforward and attainable path to launch.

However, it’s been anything but. Critics have referred to the SLS as the “Senate Launch System,” a jab at the budget being spread around to contractors in influential states and Congressional districts. Just as SLS was first getting underway, the Obama administration was also pushing for commercializing launch services. No one had reason to expect the rapid rise of SpaceX’s reusability mantra, one that other companies are now duplicating due to cost savings.

The SLS was never meant to compete with these reusable launch systems. Still, as we set our long-term sights on deep-space exploration, the SLS could be seen as a dinosaur.

For many, it’s been painful to watch heritage SLS aerospace contractors like Boeing struggle to get the rocket off the ground, all while new space startups continue to revolutionize the industry. Initially, Congress, in bipartisan fashion, was appalled by the notion of moving away from large, established, and costly aerospace companies — those which also often serve as defense companies, too. Congress also specifically mandated the SLS development be awarded to Boeing and others, like Northrup Grumman.

In all, the total cost of developing SLS and Orion, as well as a failed rocket predecessor called Ares, is somewhere around $50 billion.

Veteran space watchers wonder if SLS will have a long life now that New Space is nimbly competing with older contractors. SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy costs well north of $100 million per launch. The SLS? About $4 billion per launch, some sources say. And according to veteran space reporter Eric Berger, it’s at least $2 billion per launch.

But don’t forget about SpaceX’s Starship.

“If Starship reaches even half its potential,” Berger writes in Ars Technica, “it will exceed the SLS rocket in every possible way. It’s more powerful, far less expensive, and fully reusable, and it can launch hundreds of times a year — not once.”

This much is certain: Barring disaster and assuming a successful first launch, SLS will be NASA’s main workhorse for the time being. But Berger and others have their eyes fixed on Starship, which has the potential for carrying out far more launches at far lower costs. The Starship Human Landing System (HLS) also has been selected as the Artemis missions’ lunar lander of choice. It was a bold move by NASA to do that — a vote of confidence in a company that has already permanently changed the course of human spaceflight. And that decision might have more consequential results too: Starship might even entirely replace the SLS and Orion down the line.

In any case, the Artemis missions are happening. Humans are on a path to deep-space exploration. We are returning to the Moon. Those who have long advocated for this can’t help but be pleased if and when the SLS succeeds. And journeys to Mars look more likely now than at any time since the heyday of the Apollo program.

Like the Saturn V, the SLS may not be as long-lived as its creators imagined. But unused Saturn Vs are museum pieces now. And that’s not such a bad fate for a rocket.