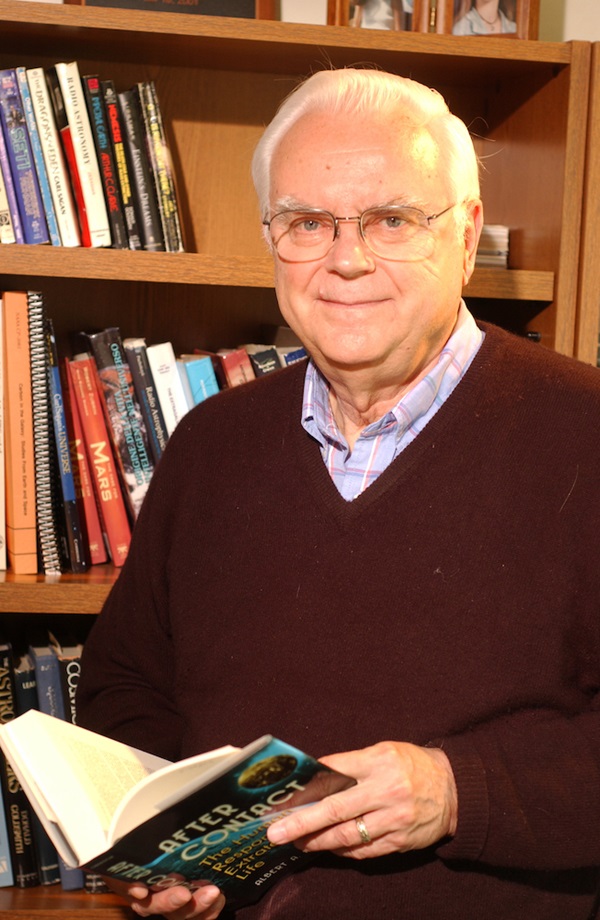

Frank Drake, famous for pioneering the modern-day search for extraterrestrial intelligence, died in the early morning hours of Sept. 2 at his home in Aptos, California. He was 92.

Drake established the methods still used today by those who hope to prove the existence of alien societies. As a result, Drake was an astronomer known to just about everyone. After all, his search for radio signals coming from two nearby Sun-like star systems, playfully christened Project Ozma, is covered in most astronomy courses.

To me, however, Frank was a friend and mentor. When we were both at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute (better known as SETI), his office was just a short walk from my own. He was always happy to lend an ear, regardless of if I wanted to talk about astronomy or something else. He could always be counted on to provide insights that few others could offer.

Radical beginnings

In 1960, Drake, who was fresh out of grad school, took a position at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Green Bank, West Virginia. There was one large instrument there, an 85-foot-wide (26 meter) antenna from the Blaw-Knox Company. Observatory director Otto Struve encouraged Drake to think of an interesting experiment to do with this new radio telescope.

A young and creative astronomer, Drake proposed searching for narrow-band radio signals coming from the sky. He reasoned that such signals would not be generated by natural processes, but instead by transmitters under the control of beings with intelligence comparable or superior to our own. Unlike his predecessors Gulielmo Marcoi and Nikola Tesla, Drake turned his gaze not to Mars, but to two stars about a dozen light-years away: Tau (τ) Ceti and Epsilon (ε) Eridani.

While the idea of trying to eavesdrop on other galactic societies is familiar today, it was a radical suggestion in the ‘60s; one that might have elicited derision from the wider astronomical community. To avoid that, Drake limited the scale of his experiment, spending only a few weeks listening and about $2,000 on new equipment.

Despite Drake’s attempts to keep the search low-key, it attracted worldwide attention. And although he didn’t hear any extraterrestrials, Drake’s Project Ozma was recognized as a fundamentally new way to explore the cosmos.

The National Academy of Sciences then suggested that Drake organize a conference to discuss the fledgling field. At a meeting held at Green Bank in 1961, Drake unveiled a simple equation that encapsulated the parameters relevant to gauging the number of broadcasting societies in the galaxy. This simple formula is now known as the famous Drake equation. It remains, like Project Ozma, standard fodder for countless introductory astronomy courses.

In the years since its creation, I have occasionally seen papers claiming that the Drake equation is somehow incomplete; that it’s missing some important term. I once asked Drake about this, and he laughed. He was aware of many such claims but insisted that the existing formulation includes all the relevant phenomena. A touchier matter concerned the equation’s name, as some have suggested that it really should be called the Drake-Sagan Equation. But this work was Drake’s alone.

A quiet trailblazer

When I joined the SETI Institute in 1990, Drake was president. He was ensconced in a roomy office with a relaxing view of trees and grass, a scene that was already rare in the Silicon Valley.

In one of our conversations, I recall asking him if he had any advice for people at the beginning of their careers. He smiled, then responded in a soft voice: “Well, you’ve got to know your limitations.” At first, I thought this sounded like something Clint Eastwood had muttered in a movie. Eventually, however, I recognized the insight and utility of his answer.

I was not the only one to receive Drake’s shrewd advice either. Like many organizations, the SETI Institute has weekly meetings to discuss its current and future activities. I recall Drake sitting at the conference table during these meetings, head down. On first impression, he didn’t seem to be particularly interested in whatever was being discussed. However, when he did finally contribute, his comments, delivered in his low-key manor, were invariably central to whatever issue was at hand. He always struck straight to the heart of any matter.

But Drake was never an impatient listener. He was, to my mind, one of the last nice guys around. He was never moody, never angry, and he didn’t show the slightest annoyance if you walked into his office and took his attention away from whatever he was doing. That truly impressed me, and I once asked about this equanimity in the face of random interruptions. I assumed he might have developed this rare talent in response to dealing with his children. “No,” he said. “It was from dealing with my students.” Looking back on this moment now, it is a reminder of how many lives and careers he touched.

Everyone familiar with astronomy recognizes the discipline’s trailblazers; its historical heroes from Copernicus to Hubble. But almost none have had the opportunity to know them personally, to interact with them in daily life as opposed to reading their names in a textbook. Drake was a pioneer, one that thousands of astronomers have listened to or met. That’s a rare privilege, for few disciplines are still blessed with the participation of those who started them.

Someday, astronomers wielding large antennas may pick up a thin radio squeal from the cosmos that will tell us we have company in our galaxy. That will be a hugely transformative event for our species. And such a discovery, should it ever occur, will be largely thanks to the man who first suggested that the search was worth pursuing.

Frank Drake may be gone, but his legacy will persist as long as humans glimpse up at the night sky and wonder if there’s anyone looking back.