In the search for extraterrestrial life, astrobiologists face a bit of a conundrum: How wide of a net should they cast when searching for life elsewhere in the cosmos?

After all, scientists have been shocked by the extreme environments life manages to thrive in here on Earth. So it isn’t too hard to imagine that the universe might be teeming with the unexpected. However, with human interplanetary travel still more science fiction than reality, researchers are limited by the technology and knowledge of life currently accessible. But that doesn’t mean they can’t get creative.

Identifying candidates for life

In astrobiology, a popular technique for determining whether an exoplanet might support extraterrestrial life involves analyzing the atmosphere of the planet via the transit method.

When a distant star passes behind its exoplanet from the point of view of Earth, starlight filters through the atmosphere of the exoplanet before making its way to our instruments. Using a spectrograph, astronomers can separate that filtered starlight into its constituent components. Analyzing this resulting emission spectra can provide astronomers with a detailed log of the chemistry likely present in the atmosphere of the alien world.

Astrobiologists who investigate the atmospheres of exoplanets this way are looking for what they call biosignatures, or chemical evidence for past or present life. Since we know that certain biological processes on Earth leave chemical traces in our atmosphere, if we manage to identify those same traces in the atmospheres of other planets, then we would have good reason to believe living organisms inhabit or inhabited those other worlds.

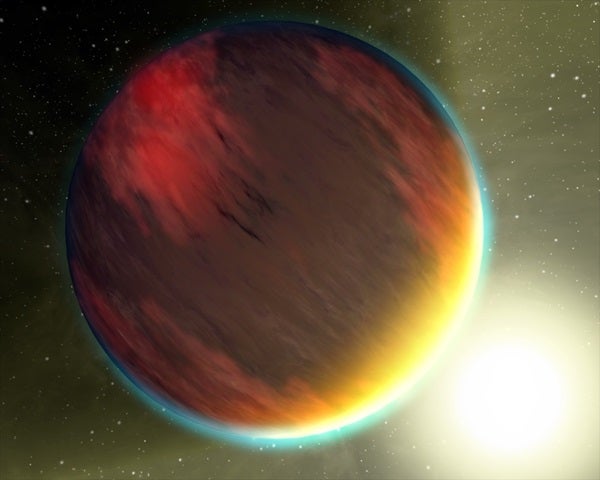

Currently, the transit method has been mostly used to analyze giant, hot planets that orbit very near their host stars. That’s because they are much easier to spot and confirm, as these so-called hot Jupiters block more starlight more frequently than smaller, more distantly orbiting worlds.

But hot Jupiters are unlikely to be habitable locales for life — at least life as we know it. To fully realize the potential of the transit method in detecting possible life-supporting planets, astronomers must seek improvements in our technology for detecting and isolating the emission spectra of exoplanets.

Fortunately, NASA’s proposed FINESSE mission, the European Space Agency’s proposed Exoplanet Spectroscopy Mission, and the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will provide scientists with a look at many new potential homes for extraterrestrial life, as well as provide them with a vastly improved ability to analyze the emission spectra of exoplanets.

There are, however, certain problems with the biosignature method of detecting life on alien worlds.

The problem with assumptions

Some astrobiologists argue that we should be open to the possibility that extraterrestrial organisms could be very different to life as we know it. One of the most basic signs that an entity is an organism on Earth, that it produces carbon dioxide or water as a product of respiration or photosynthesis, may not apply as the universal indicator of life elsewhere in the cosmos.

Even our understanding of biosignatures on Earth is still murky, as discoveries in exotic metabolic processes can attest. It is an ongoing debate as to how astrobiologists might distinguish between the chemical compositions of alien atmospheres that indicate the presence of life and those that don’t since we cannot assume that extraterrestrial life will produce the same biosignatures of living organisms on Earth.

So, if the parameters set out for identifying life in the cosmos is currently too narrow, how can we search for extraterrestrial life if we don’t necessarily know what we are looking for?

According to Princeton philosopher David Kinney and Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) principal investigator Christopher Kempes, we should be looking at planets with the strangest atmospheres.

Strange bedfellows

Planets with peculiar atmospheres, relative to a representative sample, should be regarded as the most likely settings for extraterrestrial life. The parameters for ‘anomalousness’ should be data-dependent, rather than being based on assumptions about life that may be Earth-centric.

“Conceptually, there must be some common thread between all things in the universe that we want to describe as being alive,” says Kinney, who co-authored the paper, published June 22 in Biology & Philosophy, outlining their theory.

In moving away from the assumption that the thread must be chemical, Kinney and Kempes hope to avoid some common pitfalls, namely abiotic processes that mimic biotic ones. “There has been a long history in exoplanet research of people finding abiotic mechanisms that produce candidate biosignature gases,” says Kinney. “Our method circumvents this issue a bit by saying ‘let the data tell us what is anomalous.’”

Still their argument does rest on a few core assumptions. First that a given sample of exoplanets can be statistically representative of all the atmospheres in the universe. While over 5,000 exoplanet candidates have been confirmed, scientists estimate that there are hundreds of billions of planets within the Milky Way alone. It also assumes that life in that set of observable exoplanets is rare and that living organisms tend to leave biosignatures in the planets they inhabit.

Although each of these assumptions can be questioned, it follows that if the chemical composition of a planet is unusual, then a possible cause of this unusual composition is that life exists on that planet. The foundation of their method comes from a paper published in Astrobiology in 2016 in which a list of roughly 14,000 compounds likely to appear as gasses in the atmospheres of extrasolar planets’ is outlined.

“A key takeaway from our paper is that when science is conducted under conditions of deep uncertainty, a scientist often must be willing to speculate,” says Kemples. “That is, they must be ready to make assumptions that go beyond their data, and to then explore the consequences of those assumptions. Whatever one discovers very likely won’t verify those initial assumptions, but this method can nevertheless lead to extraordinary breakthroughs.”