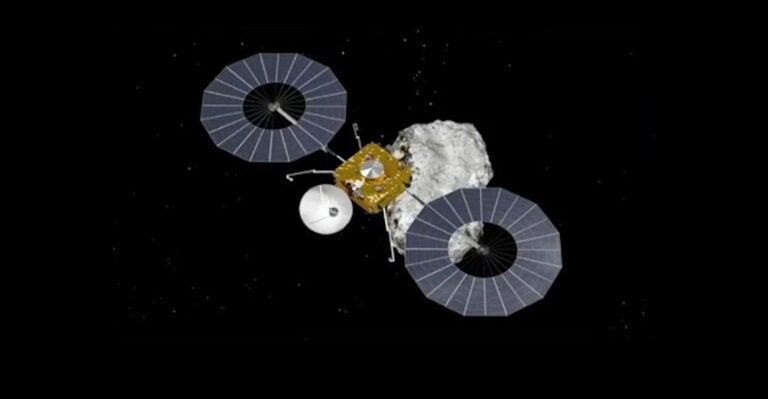

The United Arab Emirates’ fledgling space program took another step forward last month, securing an agreement to collaborate on China’s planned Chang’e 7 lunar mission, set to land near the Moon’s south pole in 2026. The Mohammed bin Rashid Space Center (MBRSC) in Dubai will build a small robotic rover, which will hitch a ride on the Chang’e 7 lander, according to the agreement signed Sept. 16 between MBRSC and the China National Space Administration (CNSA).

The deal is the first space collaboration between the two nations, and comes as both nations seek to ramp up their presence — and partnerships — in space.

The UAE’s planned rover, named Rashid 2, will be a follow-up to Rashid, which will launch to the Moon as early as next month on a Falcon 9 rocket, stowed aboard a lander built by Japanese company ispace.

The UAE already has a successful Mars mission underway — the orbiter, named Hope, arrived last year and has been studying the martian climate ever since. That mission, the first to Mars from the Arab world, featured collaboration between MBRSC and three U.S. universities: the University of Colorado Boulder and its renowned Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, Arizona State University, and the University of California, Berkeley.

The Hope team is also working with NASA’s MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution) mission, which has been orbiting Mars and studying its atmosphere since 2014.

UAE navigates space blocs

Because the UAE has collaborated so closely with the U.S., its bilateral agreement with China surprised many space watchers.

The past several years has seen the emergence of what many space policy experts refer to as space blocs, competing for influence (and, to critics, leaving smaller nations behind). One group is led by the United States: Since October 2020, over 20 nations — including the UAE — have signed the Artemis Accords. Drafted by NASA and the U.S. Department of State, the agreement lays out principles for the peaceful and commercial use of space, including the lunar surface. In response, China and Russia forged closer ties, developing joint plans for a lunar outpost.

But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has strained that relationship, and could be prompting China to expand its network of collaborators. On Sept. 21, China announced an opportunity for the international community to propose to fly additional scientific payloads on Chang’e 7. At a session hosted by Chinese space officials that day at the International Astronautical Congress in Paris, SpaceNews reported that CNSA presenters made no mention of Russia.

Despite the frequent portrayal of the Artemis Accords as a bloc, the accords do not prohibit any signatory nation from cooperating with a non-signatory nation. The UAE’s bilateral agreement with China signals a desire from the UAE to keep ties with both groups, and perhaps to assert its own cooperative leadership, writes Miriam Kramer in Axios. And for China, the agreement aligns with what may be a renewed intent to seek out a broader array of international partners for its space program.

The Emirati-Chinese agreement could be a sign that the nature of these space blocs will not be as rigid as some have thought — or feared.